Though often overshadowed by her famous father, Ben Shahn, Judith Shahn, who died in 2009, was the star at Wellfleet’s Cove Gallery, which has promoted her artwork since she first exhibited there in 1972. In recent years, the gallery has set aside a room for Judith’s sparse paintings and silkscreen prints of everyday objects like rowboats, vases of flowers, and coffeepots, rendered in razor-sharp lines.

Wellfleet has remained a loyal audience for Judith’s work. “I usually sell a Judith Shahn every day,” says Liane Biron, who owns the gallery with her husband, Larry Biron. “They’re for everybody,” says Biron of the silkscreen prints. “I’ve had high school kids buy them.” The prints are accessible for their modest prices and imagery that appeals to art connoisseurs and novices alike.

This summer, in a show that opens Saturday, July 20, Cove Gallery will exhibit Judith Shahn’s work alongside that of other family members.

The exhibition, “One Family, Four Journeys,” opens a window into Judith’s early work and the formative influence of her father. It includes her siblings Jonathan and Abby, tracing the legacy of their father while also highlighting the individual voice of each artist. “The exhibition is an opportunity to speak about the whole Shahn family,” says Liane Biron.

“The connections are not necessarily in the art they create,” says Biron, who is exhibiting a diverse range of art, including paintings of bathers in Truro by Ben; figurative sculptures by Jonathan; semi-figurative ghostly works on paper by Abby; and early paintings by Judith, including scenes from the Truro home that she shared with her husband, the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Alan Dugan. Yet given all the diversity that the individual artists pursued in long careers dedicated to artmaking, it’s hard to resist looking for throughlines.

Many of the works on display became available after Cove Gallery was tasked with stewarding Judith’s personal collection, which included artwork by her father. The idea of a broader family exhibition did not take shape, however, until Biron established a relationship with Lisa Mecham, a California-based writer.

Mecham visited in 2018 and was impressed with the trove of artworks that the gallery was managing after Judith’s death. “Liane said she wished someone would write about her,” says Mecham. “That stuck with me.”

Mecham returned to California and didn’t come back to the Cape for a few years. “I couldn’t stop thinking about Judy and her work,” says Mecham. When she returned last summer and learned that no other writer had claimed Judith as a subject, she began researching in earnest. Over the past year she has returned to the Cape four times to interview people who knew Judith, research the archives at the Cape Cod Museum of Art, and visit the home in Truro where Judith and Dugan lived. She recently started writing a biography of Judith (Finding Judy is her working title), and in the fall she plans to publish a blog with archive material from Judith’s home and studio.

“Lisa made so many connections,” says Biron, who was introduced to Judith’s extended family by the writer. These connections facilitated the current grouping of work on display. For Mecham, the exhibition represents an opportunity to ponder one of her deep interests: the question of nature versus nurture. “To what extent is artistic talent inherited?” she asks.

Ben Shahn, a Jewish immigrant from Lithuania who was raised in Brooklyn in the early 20th century, came to prominence as a painter whose left-wing politics informed his creative vision. He developed an unsentimental realist language to depict the struggles of working people and comment on the political issues of his time. In 1932, he exhibited a collection of gouache paintings of the trial of Sacco and Vanzetti, which cemented his position in the political and art worlds.

Judith’s early paintings of flattened figures recall her father’s work. Biron points out a similarity between a painting Judith made in Mexico of children playing ball and her father’s painting of handball, now in the MoMA collection. In addition to similarities in subject, both artists situate their figures in flat empty spaces. In her mature work, Judith largely abandoned the figure, but her compositions retained this sense of economy.

Biron says Judith didn’t speak much about her father but recalls one thing: “Judith said that her father always told her to draw. That’s certainly what she did.” In addition to her prints and paintings, Judith produced black-and-white illustrations for the New Yorker from 1958 to 1992. In a 1994 article by Cindy Nickerson in CapeWeek, Judith says that having a famous father “opens certain doors … but it doesn’t get you in. You have to stand on your own work.”

Like Judith, Jonathan and Abby were established artists who stood on their own work, not the reputation of their father. But is their father’s influence discernible in their work? Is it appropriate to view their work in that light? These are open questions; the show doesn’t propose any particular answer.

Jonathan, who died in 2020, shared his father’s fascination with realism and the human figure in sculptures that don’t hide the lumpy clay or fibrous wood from which they were hewn. Jonathan lived and worked in Roosevelt, N.J., where his father had been involved in the Jersey Homesteads cooperative, a Utopian project created as part of the New Deal to resettle Jewish garment workers.

Abby Shahn, the only living family member in the exhibition, is represented by works on paper of quasi-figurative beings grouped together and floating in all-over compositions. The images were originally created as an accompaniment to a book of poetry, Ghosts, by Mark Melnicove. Abby, who has lived in rural Maine since the 1960s, had a retrospective exhibition of her work in 2020 at Speedwell Contemporary in Portland, Maine, where she showed paintings that hover between abstraction and figuration. Often a figure or portrait is present but obscured by whorls of expressionistic marks and bold colors.

Judith, who was born in 1929, was the oldest of the siblings but initially had a distant relationship with Jonathan and Abby. Shahn left Judith’s mother, Tillie Goldstein, when Judith was six and her brother Ezra was an infant. He married his assistant, Bernarda Bryson, and they had three children: Jonathan, Abby, and Susanna. It wasn’t until Judith’s half-siblings were teenagers that they learned about the existence of Judith and Ezra.

“Judith’s relationship with her father was strained,” says Biron. “She reconnected with him at age 21 when her mother died,” she adds.

“Ben was a difficult father,” says Mecham. “His children were trying to connect with him in whatever way they could. Judy was out of touch with him but seeing his work,” she adds. This exhibition proposes that art became a nexus of connection for the family — and perhaps a site of reconciliation.

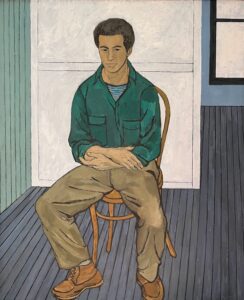

One of the most touching pieces in the show is a painting Judith did of her half-brother Jonathan. She paints him seated in an empty room. She looks at him straight on; his body is at ease, but his eyes are downcast. The painting is a gesture of connection, not only between artist and model, but between a sister and brother, united by an uneasy family history and devotion to art.

Another intimate painting in the exhibition is an image Ben painted of Judith as a child in her mother’s arms. It references the Madonna and child, a common motif in Western art, but in keeping with his values as a social realist, Ben represented the mother as a sturdy working woman with large hands. Yet there’s a tenderness in the picture. Judith looks out at the painter — her father — with open, innocent eyes. The painting hung over Judith’s mantle in Truro.

Judith, who never had children, left her estate and Truro home to her brother Ezra when she died in 2018. When Ezra died in 2020, his widow inherited the artwork owned by Judith, and the house went to Ezra’s son Zach, who followed in his father’s footsteps as a professor at Hunter College. Ezra’s widow is working with Cove Gallery to make the artwork from Judith’s collection available to the public and potential collectors.

Judith’s Truro home on Perrys Hill Way (currently on the market for $1.1 million) features prominently in the show. “My work reflects where I am at home,” she said in a 1994 interview in Cape Cod Antiques & Arts. In her early works, Judith paints images of Truro’s rolling hills framed by her home’s screened porch. An antique lamp shows up in multiple works across decades. Biron brought the item into the gallery to show alongside the paintings.

Other objects from Judith’s home on display in the gallery include a black-and-white photograph of her as a toddler taken by Walker Evans. Evans, famous for documenting the Great Depression, was Ben’s good friend. Ben and Goldstein bought the Truro house in 1924, and until the dissolution of their marriage it was a place where the family summered and entertained guests, including Evans, who photographed Provincetown’s Portuguese community.

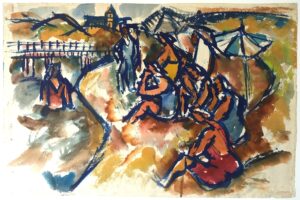

Ben’s connection to Truro ended when Tillie got the house after their divorce. A few works on paper record his local output. In one expressionistic piece, he depicts a summer scene of bathers on a Truro beach. The painting represents one thread tracing Ben’s connection to Truro. Other threads lead to his children or between the house in Truro and Judith’s work. Taken together, the show weaves a tapestry of connections and represents a reunion of sorts, tying together people and places across one family.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article, published in print on July 18, incorrectly reported the year of Judith Shahn’s death. It was 2009, not 2018.

One Family, Four Journeys

The event: The Art of the Shahn Family

The time: Opening Saturday, July 20, 6 to 8 p.m.

The place: Cove Gallery, 15 Commercial St., Wellfleet

The cost: Free