As a boy growing up in the 1950s, paradise was a pine-paneled cottage in the Surfside Colony at Lecount Hollow Beach.

A few of you cringed as you read that sentence. A few others might have sensed that there was something not exactly right about it but couldn’t quite say what it was. All right, I’ll tell you.

It’s called a dangling participle. Fixing grammar is not really a big part of the work of being a newspaper editor. But we do spend a lot of time here tucking participles into place.

One of the best books on writing, The Elements of Style by William Strunk Jr. and E.B. White, is my go-to for diagnosing problem sentences. Rule number 11 in their elementary rules of usage reads as follows: “A participial phrase at the beginning of a sentence must refer to the grammatical subject.”

In my example above, the participle, or verb describing the action in the opening phrase, is “growing.” The reason it’s “dangling” is that it doesn’t go with the main subject of the sentence, which is “paradise.” Paradise might be a pine-paneled cottage, but it is not “a boy growing up.”

To fix the sentence, you have to rewrite it, perhaps this way: “As a boy growing up in the 1950s, I thought paradise was a pine-paneled cottage….” Or “When I was a boy growing up in the 1950s, paradise was a pine-paneled cottage….” Now the phrase at the start of the sentence makes sense in relation to the subject.

Strunk and White point out that sentences violating Rule 11 are often absurd: “Being in a dilapidated condition, I was able to buy the house very cheap.” And “Wondering irresolutely what to do next, the clock struck twelve.”

To spot these unfortunate sentences and repair them, you need to be able to identify the various parts of a sentence and take a close look at how they’re fitting together (or not). I wonder if that’s part of 7th-grade English the way it was when Miss Martini taught us to diagram at Thomas Jefferson Junior High. I’ve read that diagramming is out. “Those hours spent diagramming sentences and memorizing parts of speech don’t help and may even hinder students’ efforts to become better writers,” wrote Michelle Navarre Cleary in the Atlantic in 2014. But that might be because it became little more than a boring rote exercise.

I think it’s a great way to learn about sentences and ought to be fun, not boring. I propose, therefore, that the Independent and its readers revive a dying art.

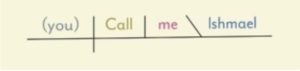

The above diagram of a famous Herman Melville sentence is from the book Sentence Diagrams of Great Literary Openers.

The Independent hereby extends a call to action and an invitation: we’re looking for someone who loves to diagram sentences to create a regular puzzle for this newspaper to alternate with Sophia Maymudes’s remarkable crosswords (yes, there is one this week: see page B12). Write to me if you want to be our new puzzler, and, please, no dangling participles.