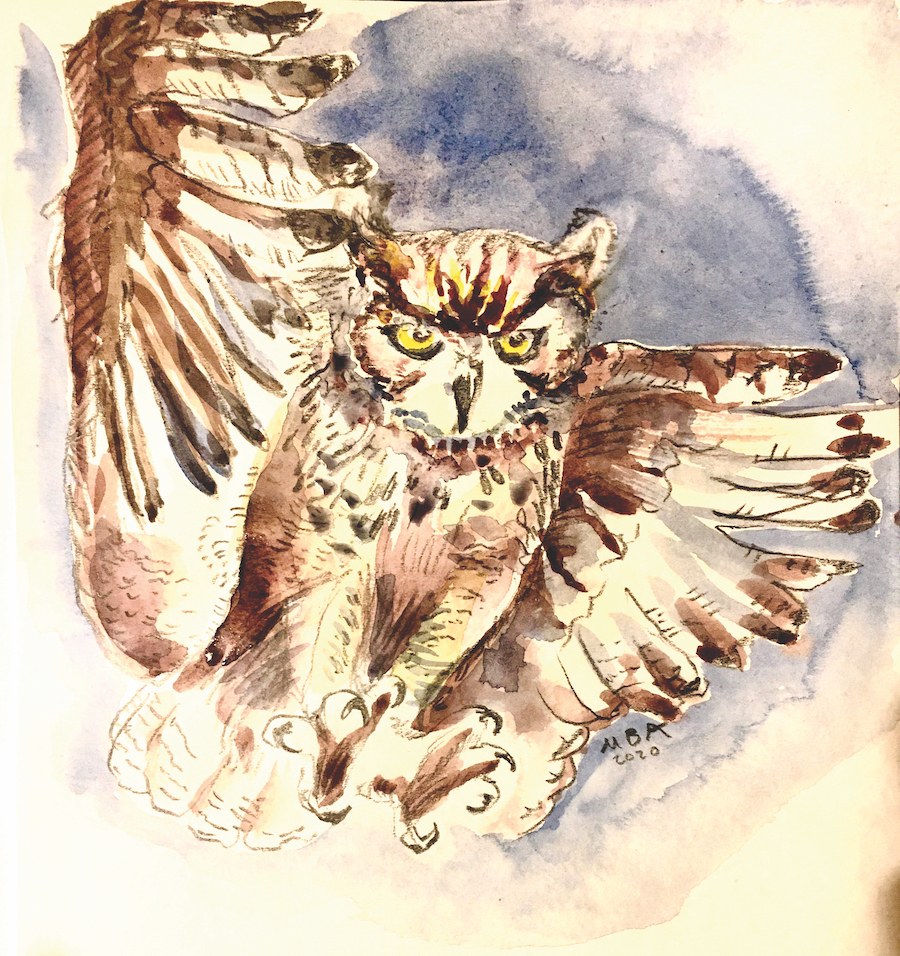

In the deep January nights, when the light of the Wolf Moon falls like ringing iron through the trees, from Tom’s Hill and Cathedral Hill on either side of the marsh and Little Pamet River come the calls of the great horned owls, those five-part queries and responses that translate into something like, “Can you hear me?” and “I can hear you,” “Are you near me?” and “I am near you.” (Brendan Galvin’s text continues below the Mark Adams watercolor)

Great horned owls go through this chthonic courtship ritual every year, and lying deep under quilts, we can almost set the year’s clock by them. In a few months, after their offspring have fledged and left the nest, some nights we’ll hear one or the other owlet landing with a thump on the roof over our heads. Or one day, I’ll look up from turning the soil in the potato bed or feeding compost into a tomato patch because I just heard something say “Schrreeep!” and there’ll be an owlet watching me with those black pupils surrounded by bright yellow, the corpse-candles of folklore.

But before that can happen, the male owl of the two calling back and forth out there has to bring to the nest his courtship gifts, presentation pieces he lays on the brim of a matted construction site the size of an automobile tire. Sometimes it’s an old hawk’s nest the two owls have appropriated; other times it’s a nest they’ve returned to year after year, since they’re monogamous. The gifts consist of rabbits, skunks, cats, mice, moles, voles, toads, frogs — you name it. As the female sits on her eggs, there’s liable to be a heap of fur, or rather furs, hanging over the nest’s edge, though not elegantly.

For years, two owls used a nest in a pine about 150 feet from our back door, and that meant there wouldn’t be any frogs in the garden and that, walking the dog, I’d occasionally find a dead rabbit by the side of the road, intact but for a surgical-looking slit at the back of its head where the owl went for its brain. Owls apparently consider brains a delicacy, and when there’s plenty of food around, they may just leave the rest of the victim. Perhaps that’s what the horned owl that zipped down just above my head intended one night at dusk, before it flew off and got lost among the trees. Surprised — maybe even embarrassed — to discover there was more to me than a sparse comb-over of white hair.

Since great horned owls swallow their smaller prey whole, they have to regurgitate “owl pellets” containing the parts that won’t pass through their digestive systems without doing damage. These pellets are small white packages that fit in your palm, dropped wet onto the ground from a tree branch where the owl was sitting. Sometimes there’s a streak of whitewash down the side of a tree or on some leaves, indicating where one has fallen. When they are dry, they can be opened, and at least some of what the resident owl has eaten recently can be deduced from the contents. Teeth and a variety of small bones that look like parts from an old typewriter might be present. There might be a swatch of fur, even a set of bird’s feet clutching the air as if still in pain.

It isn’t unusual for us to get a whiff of skunk in broad daylight and begin looking for an owl in the trees, because the mephitic skunk spray temporarily blinds the bird, who’s out in the sun because he can’t tell if it’s dark or light. For years, we observed the annual courtship ritual of the owls, the occupation of the nest, and the owlets at the edge of the nest crying to their parents for food as the male and female decimated the area’s small mammal population to stuff the throats of their offspring. Sibling rivalry begins early in the nest, we discovered, with the stronger of the offspring getting the most food. Usually two owlets could make out OK, but if there were three, the weakest one was usually doomed.

Fledging began when one of the little ones climbed up on the edge and fell out onto the ground. Or when the parents decided they’d had enough and nudged their offspring out. Then began a period of wandering around on the ground and learning to make short flights from branch to branch, under the eyes of one parent or another. One spring evening, I looked out the kitchen window and saw an owlet trying to get back into the nest. It was shaggy looking and had huge feet, like one of those stuffed school mascots. It would get about 10 feet from the trunk of the pine the nest was in, take a run at the tree, and continue running right up the trunk until gravity kicked in and it dropped back to the ground. It was still trying this ploy when it became too dark for me to see it anymore.