Marcia Marcus, a figurative painter known for her psychologically rich self-portraits, inventive use of performance in painting, and summers spent in the dune shacks of the Province Lands, died in a nursing facility in New York City on March 27, 2025. She was 97.

A bold and observant artist who came of age amid the vibrant postwar New York art scene, Marcus defied categorization. Her works are in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Smithsonian, and major New England museums. She exhibited annually at the Provincetown Art Association in the 1950s and ’60s, and her work was shown in a wide range of Cape Cod venues including the Sun Gallery and the Zabriskie Gallery through the late ’70s.

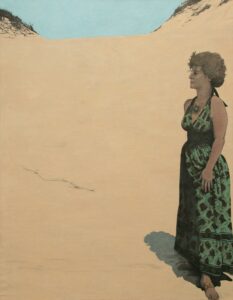

Marcus was rediscovered in 2017 amid fourth-wave feminism, having faced steep obstacles as a woman in the mid- and late-20th-century art world. She entered a field where women made up half the talent but received only a small fraction of the recognition. But she lived long enough to see her work celebrated alongside the leading artists of her time. Marcus’s paintings blend visual interest, intellect, and narrative with the figurative, offering deeply personal yet universally resonant depictions of identity.

She was born Marcia Helene Feitelson on Jan. 11, 1928 in Manhattan, the elder of two daughters of Frieda (Gelband) Feitelson, an accountant, and Irving Feitelson, a department store window dresser. She wanted to be a fashion designer, but her mother insisted that she go to college and perhaps become a teacher.

Marcia showed an early affinity for drawing and photography. She earned a B.A. from NYU in 1949, studied at Cooper Union from 1950 to 1952 — where she met lifelong peers Alex Katz and Lois Dodd — and later trained under master painter Edwin Dickinson at the Art Students League. Dickinson’s emotional depth and muted tones quietly informed Marcus’s own work, even as she forged a style of her own.

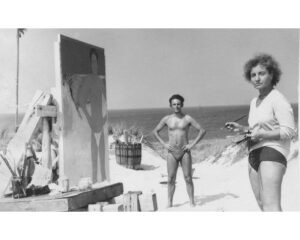

She first came to Provincetown in 1952 and returned nearly every summer for the next two decades, living and working in the C-Scape dune shack. In a letter dated 1959, written while sipping bourbon and cooking soup on a kerosene stove in another dune shack owned by Graham Giese and Tony Vevers, she wrote: “Life is peaceful & like man — happy.” The letter, full of beach roses, musings about the tides, and the practicalities of a life lived half-wild — using a washtub to bathe in sun-warmed water and reading books in a makeshift chair at low tide — captures the essence of her time in Provincetown.

Her summers were hardly idle. She was always working. Even then, she was producing art with a distinctive voice, using pastels in a makeshift studio, painting fellow artists and lovers — one was Willem de Kooning, according to Marcus’s New York Times obituary by Penelope Green — and experimenting with new forms of expression. She was among the first to merge performance and painting through “Happenings,” a radical form of early performance art. Her 1960 piece In the Garden: A Ballet, staged with Red Grooms and Bob Thompson, placed her in the pioneering ranks of that movement.

Marcus’s portraiture — of others and herself — remains her most enduring contribution. Whether depicting art-world luminaries like de Kooning, Lucas Samaras, and Jill Johnston, beloved Cape Cod artists like Myron Stout, Edwin Dickinson, and Rachel Brown, or her own unflinching image across decades of self-portraits, Marcus made interior life visible on canvas. Her work delved into themes of female desire, motherhood, aging, and race long before these topics became central in the art world.

In a 1975 interview for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, she described her deep love for Provincetown: “But just in terms of the place, I absolutely fell madly in love with it, like I entered on a sunshiny day with the tide out and the flats just sitting there and everything was sparkling. I thought, ‘Oh, my God, this is it. Home at last.’ ”

Cape Cod’s light and flora suffused her landscapes. Its community — intimate, eccentric, and often heartbreakingly human — colored her storytelling. She once described how her sister got lost trying to find her shack, only to stumble across artist John Grillo on the beach, miserable and lovelorn. These were the rhythms of her summers — equal parts grit and grace, community and solitude.

Though she exhibited widely in the 1960s and ’70s and taught at the Rhode Island School of Design, Cooper Union, Vassar, and NYU, self-promotion in an often indifferent art market proved a challenge. “As she aged, it was harder to do the hard work of marketing her work,” her daughter Kate Prendergast recalled.

Marcus experienced a resurgence in the last decade of her life, beginning with the 2017 award-winning exhibition at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery, “Inventing Downtown,” and later that year with the critically acclaimed solo show “Role Play: Marcia Marcus, 1958–1973” at Eric Firestone Gallery in New York. Critics and curators alike were reawakened to the power of her work.

In 2026, the Provincetown Art Association and Museum will mount a major solo exhibition of Marcus’s work. “She painted Provincetown not just as a place, but as a way of being — sincere, vulnerable, curious,” said PAAM Director Christine McCarthy. Her work is currently on exhibit through June 21 at the Lévy Gorvy Dayan Gallery in Manhattan in the show “The Human Situation: Marcia Marcus, Alice Neel, Sylvia Sleigh.”

In 1947, Marcus married Harry Gutman; the marriage lasted a year. She changed her last name to Marcus, which was her maternal grandfather’s first name. In 1959, she married Terence Barrell, whom she had met in Provincetown, and they had two daughters. They divorced in 1972.

Marcia is survived by her daughters, Kate Prendergast of New York City and Jane Barrell Yadav of Yonkers, N.Y.; her sister, Barbara Rose of Taos, N.Mex.; her nephew, Jason, of Taos; her grandchildren, Mateo, Christopher, Radhika, and Kedar; and her great-grandchildren, Frieda and William.

“There’s somebody for everybody,” Marcia wrote in the dunes more than 60 years ago, “and everything comes to he who waits — however impatiently.” Marcia waited, worked, and loved fiercely. And in her art, she gave herself — unsparingly — to the world.