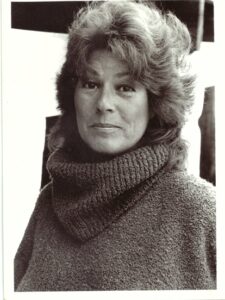

Alice May Brock of Provincetown, made famous by Arlo Guthrie’s 1967 song “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree,” died on Nov. 21, 2024 at the Lily House hospice in Wellfleet. Her caregiver Viki Merrick confirmed the cause as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Alice was 83.

“I was conceived on Long Point,” she said in a 2017 interview with Jeannette de Beauvoir, and she declared her childhood Provincetown vacations with her family “the best summers of my life.”

“I used to say,” she wrote on her website, “ ‘When I grow up, I want to live in Provincetown and paint pictures.’ ”

So, when Alice pulled into Provincetown in 1979, it was as much a homecoming as a fresh start. She used a shoebox full of quarters, the residue of her final restaurant venture, to rent an apartment. “My dreams have come true,” she later wrote, telling the Boston Globe in 2009 how grateful she was for every “beautiful day in paradise.”

One of two daughters of Joseph F. and Mary (Dubrovski) Pelkey, Alice was born on Feb. 28, 1941 in Brooklyn. An idealist as a young woman, Alice involved herself in left-leaning politics in the 1960s, registering with the Socialist Workers Party and becoming a founding member of the Students for a Democratic Society and the Fair Play for Cuba Committee.

She graduated from White Plains High School in New York in 1958 and went on to Sarah Lawrence College, dropping out in her sophomore year and moving to Greenwich Village in 1960. There she met architect Ray Brock, 13 years her senior, whom she married in 1962.

“I was still very involved in politics,” she told Berkshire Magazine in 2022, “and Ray didn’t want me to have that other life. He wanted to get me out of there. My mother wanted to get me out of there, too.” The couple ended up working in western Mass. at the Stockbridge School, a progressive private co-ed high school that closed in 1976, where Alice’s mother was the registrar. Alice became the school’s librarian and Ray a shop teacher.

Relations between students and staff were relaxed at the school, and the students, including Arlo Guthrie, son of folksinger Woody Guthrie, were drawn to Alice, hanging out at her cottage. After a year, Alice and Ray returned to New York, but they came back to the Berkshires when Alice’s mother gave them a deconsecrated Episcopal church in Housatonic as a wedding gift and they set about renovating it.

The students they knew had graduated, but they returned from college to visit. At their first Thanksgiving gathering, Arlo and his friend Rick Robbins offered to take the debris from the renovation to the dump, which was closed. They threw the debris down a ravine and were later arrested for littering. The rest of the story is well known from Arlo’s song.

At the time, Alice did not actually have a restaurant; she simply fed visiting students and other guests. With her mother’s help, she rented a diner in Stockbridge, which, Alice told Berkshire Magazine, “got me out of the house, and I got my own money.” The latter was important because Ray controlled their finances, giving her only a small allowance.

Alice’s only restaurant experience was as a waitress, but, she said, “I loved to cook. I just winged it.” And she was successful, noting in her 1976 autobiography, My Life as a Restaurant, how rising stars performing at the Berkshire Playhouse frequented the place. “Dustin Hoffman and Gene Hackman liked hamburgers with onion, green peppers, and an egg on them,” she wrote, and Anne Bancroft “helped me clear the table.”

In 2007, Alice told All Things Considered on NPR: “In my restaurant I rarely hired people who were trained. That wasn’t important. As long as you could take down an order, treat people well, and give them an experience they would remember, I didn’t care if you were dressed up as a piece of broccoli. In fact, it was the oddity that brought richness to everyone.”

“You could trust her,” Merrick told the Berkshire Eagle. “You could rely on her. And she made a lot of people feel that way. Between running a restaurant and how she was in the world, she gave a lot of people, especially women, permission to try things and be themselves.”

“Years ago Alice gave me a job for which I was completely unqualified,” one of her former employees wrote in an online tribute. “I worked my ass off. She yelled at me all summer. It was the best job of my life.”

When Arthur Penn, the director of Bonnie and Clyde, heard the Thanksgiving littering story from Alice’s father, he decided to make a movie about it. On the day Alice and Ray’s wedding scene was shot for the film, their divorce was finalized.

The movie was released in 1969, the same year The Alice’s Restaurant Cookbook was published; the film outraged Alice because of how it misrepresented her, and Arlo walked out of the premiere after 20 minutes for similar reasons.

In the decade from 1969 to 1979, Alice opened two other restaurants, the first named Take Out Alice and later Alice’s Restaurant, and the second Alice’s at Avaloch; the latter was well reviewed in the Washington Post. When it failed, however, Alice left for Provincetown with the quarters from the vending machines.

In 1983, Alice bought 69 Commercial St., a house that had been made into “a dramatic expression of Catholic piety,” according to David Dunlap’s Building Provincetown. It included a private chapel on the third floor (consecrated by the bishop of Fall River).

“The whole house was filled with icons, including martyrs with their eyes gouged out,” Alice told Dunlap. There she established her studio.

“The light is so wonderful,” Alice wrote, and “the people are pretty wonderful too, contrarians, cranks, queers and curmudgeons, a great mix of round pegs that stopped trying to fit into square holes. Plenty of space to be yourself or invent a new self. I fit right in.”

After 40 years in Provincetown, working in restaurants and painting, Alice found herself in failing health and needing a new place to live. Money, something she had never respected — “until now,” she told the Independent’s K.C. Myers — was in such short supply that her friend Dini Lamot, a.k.a. Musty Chiffon, a former member of the late 1970s punk band Human Sexual Response, organized a GoFundMe campaign titled “You Can Give Anything You Want” to help her. It raised $170,000.

Alice had started painting stones when she was in her early 20s. “I used nail polish,” she told Viki Merrick on WCAI. She was moved by the thought that so many people walk along the beach, daydreaming and looking at stones, some still wet and glistening in the sun. What if, suddenly, “A stone is looking back,” she wrote on her website. “That vision really tickled me.”

Her painted stones became a form of living art that popped up almost everywhere. Alice put them on supermarket shelves, in sugar bowls, along bike trails, and on fenceposts; she even slipped them into people’s pockets. Her stones have been placed at the Louvre, the Museum of Modern Art, the Hermitage, and the Tate gallery. They have been carried to the top of Mount McKinley, brought to the bottom of the Grand Canyon, and placed on beaches in Alaska, Venezuela, and New Zealand. One was dropped from the Great Wall of China.

Alice was “a sublime alchemist,” wrote Jim Bruenn in a letter in Berkshire Edge. “She reveled in creating improbable and magnificent combinations from the most improbable and unlikely sources.”

Improbable and unlikely aptly describe Alice’s enduring place in the American popular imagination, captured in a 2019 Thanksgiving newsletter written by the president of Sarah Lawrence College. Evoking the traditional Thanksgiving image of a family feasting on turkey and trimmings, the newsletter adds that for some the day “involves an annual listen to Arlo Guthrie’s ‘Alice’s Restaurant,’ with its SLC connection to the real Alice, Alice Pelkey Brock ’62.”

Alice is survived by her stepchildren, Becca, Jono, and Fletcher Brock, two grandchildren, one great-granddaughter, and two great-great-grandchildren.

In lieu of flowers, donations in Alice’s memory can be made to the Lily House in Wellfleet.