Pioneering television documentary filmmaker and longtime Truro summer resident Peter Poor died on April 4, 2024 at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City, where in the 1950s he had helped his father, Henry Varnum Poor, paint murals. Peter was 97.

He produced and directed documentaries for all three of the major television networks, and his work included The Twentieth Century and Air Power, both narrated by Walter Cronkite.

Peter was born on May 17, 1926 in New City, N.Y. His father, a painter, architect, sculptor, and potter, also painted the frescos at the Dept. of Justice in Washington, D.C. and the Post Office murals in Chicago. His mother, Elizabeth “Bessie” Breuer, was a journalist and novelist who won four consecutive O. Henry Awards for her short stories in the 1940s.

Except for spending a year at age eight in France, where his parents had gone to paint and to write, Peter grew up in New City in a house his father had designed and built in 1920 as the center of an arts colony that attracted Burgess Meredith, Kurt Weill, and Lotte Lenya.

Bessie first came to Provincetown with her friends Agnes and Eugene O’Neill and the Provincetown Players in 1915, said Peter’s daughter Candida. She married Henry in 1925, and after Peter’s birth they spent summers in Truro.

“In the very early ’30s,” Peter wrote in an unpublished autobiography, “we used to spend the summer in a rented cottage on Corn Hill. One day my dad and I were at Pop Snow’s when a large sedan pulled up to the gas pumps, and a big man got out. He was like nobody I’d ever seen in Truro — he was wearing a heavy woolen three-piece suit, shirt, tie, and buttoned vest. And I was introduced to Ed Hopper.”

He recalled visiting the Hoppers at their house “on the high dune” and being impressed with Hopper’s “reserve and formality.” Peter appears as a six-year-old in his father’s painting The Disappointed Fisherman.

After World War II, Henry bought Railroad House, just 50 feet away from the tracks that ran to Provincetown. “I can’t describe how exciting it was to have that huge engine come rumbling and blowing right through our yard,” Peter wrote. “The ground shook — everything shook — we shook. We waved to the engineer and fireman, and they waved back and usually gave us a little private toot. The rest of the day was anti-climax.”

Peter went to Andover and in 1943 entered Harvard, where he studied with Wallace Stegner. He interrupted his education in 1944 to enlist in the Army Air Corps and served one day short of a year.

His most vivid memory from military service was April 12, 1945: “The day President Roosevelt died,” he wrote. “The feeling of utter despair and loss all over the base, the blind urge to get to a chapel, the feeling that the world had changed, and hope was gone, even if we won.”

A week before his college graduation in 1948, family friend Burgess Meredith offered Peter a job with New World Films, his new film company. The salary was $35 a week. He worked in film for the rest of his professional life.

In 1950, he married his childhood sweetheart, Eloise Marcovicci, and in 1951 Peter received a Fulbright fellowship to Rome, where he studied filmmaking at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, working alongside Roberto Rossellini, serving as a slate boy and as a grip on the film Roman Holiday.

Starting in 1954, he was senior editor and researcher for Air Power, reviewing some 100,000 feet of archival film in an Air Force storage facility in the Midwest. In 1957 and 1958, Peter worked on the live television series The Seven Lively Arts with Meredith and John Houseman. He then undertook his most ambitious project, The Twentieth Century, followed by The 21st Century. He worked in the field, which meant in a 1966 trip to Vietnam with Cronkite that included a dangerous low-altitude flight in a small plane from the aircraft carrier Coral Sea to Saigon, “so Walter could get a good look at things,” Peter wrote. “The co-pilot, sitting with me, got more and more nervous. ‘We shouldn’t be doing this,’ he said. ‘It’s dangerous…. But showing Cronkite a good time apparently trumped safety and regulations.”

After a piece on Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in 1974 and a 1975 documentary called The I.Q. Myth, Peter left CBS and over the next two decades worked intermittently for NBC on Weekend with Linda Ellerbee and Lloyd Dobyns and as a freelancer. But television had changed, and longer documentaries were no longer in demand.

“My father’s finances were difficult,” Peter’s son, Graham, said. “Selling the Cape property would have helped, but he would not do that.” His daughters had artistic careers of their own, “and he wanted to leave something to foster their work.” Besides, he loved Ballston Beach, which he was last able to visit in 2020.

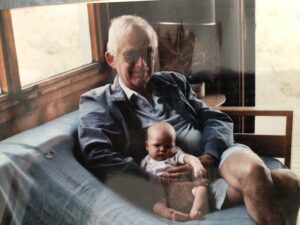

Peter is survived by his daughters, Candida Monteith and husband Bruce of Needham Heights and Truro and Anna Poor and husband Francis Olschafskie of Boston; his son, Graham Poor and wife Margaret of Mountain View, Calif.; and four grandchildren: Craig Monteith of Kingston, N.Y., Mona Poor-Olschafskie of Boston, and Theo and Mary Rose Poor of Mountain View, Calif.

He was predeceased by his wife, Eloise Marcovicci, and a grandson, Kyle Monteith.

In lieu of flowers, donations in Peter’s honor can be made to the Nature Conservancy.

Editor’s note: Because of an editing error, an earlier version of this obituary, published in print on May 2, incorrectly identified Edward Hopper as the painter of The Disappointed Fisherman. It was painted by Peter Poor’s father, Henry Varnum Poor.