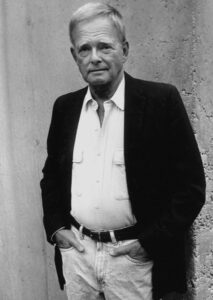

Paul Brodeur of Truro, a longtime staff writer at the New Yorker, died at Cape Cod Hospital on Aug. 2, 2023. His death, following hip replacement surgery and a bout of pneumonia, was confirmed by his daughter, Adrienne Brodeur. He was 92.

Brodeur wrote pioneering articles about the hazards of asbestos, the destruction of the ozone layer by manmade chemicals, the biological effects of microwave radiation and power-line electromagnetic fields, and other environmental and occupational threats.

In 1968, the New Yorker published “The Magic Mineral,” Brodeur’s investigation into asbestos-caused cancer and other diseases afflicting tens of thousands of workers, as well as others who had inhaled minuscule fibers of the substance. The article described the little-known history of asbestos, its myriad uses and astonishing properties, and the high death rate among asbestos workers.

It brought international attention to the problem and was used as a road map for litigation that eventually led to the bankruptcy of virtually all the leading asbestos manufacturers.

Over the next 15 years, Brodeur wrote about the hazards of spraying asbestos insulation on the steel girders of high-rise buildings — a practice soon banned nationwide — and about the cover-up of asbestos lung disease by industry officials and company doctors.

The revelations were credited with helping persuade Congress to mandate the removal of asbestos from schools and other buildings across the nation. Brodeur won a National Magazine Award, a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship, the Sidney Hillman Foundation Prize for journalism, and awards from the American Association of Trial Lawyers and the American Bar Association.

In 1974, he wrote about the threat posed to the ozone layer by chlorofluorocarbon chemicals used as refrigerants and as propellants in spray cans. His article won the journalism award of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, as well as a place in the U.N.’s Global 500 Roll of Honor for outstanding environmental achievement. A subsequent piece by Brodeur helped bring about the Montreal Protocols, an international treaty phasing out the use of chlorofluorocarbons.

No stranger to controversy, Brodeur criticized institutions and publications he found wanting with regard to health issues. He denounced a justice system under which no asbestos company official was ever charged with a crime for hiding evidence that exposure to asbestos had claimed the lives of thousands of workers. He exposed the authors of articles in leading medical journals who minimized the dangers of asbestos without revealing that they were being financed by the asbestos industry.

In 1976, Brodeur wrote two controversial articles about health hazards attributed to exposure to microwave radiation. The articles also described the ongoing Soviet bombardment of the American Embassy in Moscow with low-level microwaves that were suspected of activating listening devices in the embassy walls and of altering the behavior of diplomats stationed there. They were awarded an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellowship and expanded into the book The Zapping of America.

The debate over microwaves continues. “The fact that the World Health Organization has found microwave radiation emitted by cell phones to be a possible carcinogen, and that the American government has acknowledged that pulsed microwaves are the most likely cause of brain injuries among its diplomats and intelligence officials — a condition called the ‘Havana Syndrome’ — has kept the controversy alive,” Brodeur wrote.

Also controversial were a series of articles written in 1989 describing epidemiological studies linking childhood leukemia with exposure to the electromagnetic fields given off by power lines and electrical equipment. These findings were widely denied by the electric utility industry, but power-line radiation has also been classified as possibly carcinogenic by the World Health Organization.

In 2010, Brodeur engaged in a dispute with the New York Public Library, which proposed to delete three-quarters of a collection of papers he had donated 18 years earlier and refused his request to return the collection so he could donate it elsewhere. Following an outpouring of support for Brodeur from librarians and academicians, the library agreed to transfer the entire collection to the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University.

Paul Brodeur was born in Boston on May 16, 1931. His father was an orthodontist and sculptor who had served in the French Foreign Legion during World War I. His mother, Sarah Marjorie Smith, was an early childhood educator. He graduated from Phillips Academy Andover and Harvard University before enlisting in the Army Counterintelligence Corps and being posted to a nuclear storage depot in Germany. Following his discharge, he lived for a year in Paris, where he wrote a short story about his military experience that he sold to the New Yorker. It led to his becoming a staff member there for nearly 40 years.

During his early years at the magazine, Brodeur was a Talk of the Town reporter, covering a wide variety of events. Notable among them were the funerals of Michael Schwerner and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, a speech by Martin Luther King at the New York Bar Association, and a tribute to Charles De Gaulle after his death in 1970.

Brodeur also wrote about Native American land claims and was a strong advocate for Indian rights. He was the author of 13 books, including collections of his magazine articles, several novels, and a collection of short stories. One of his novels, The Stunt Man, was made into a film of the same title starring Peter O’Toole and was nominated for several Academy Awards. His short stories appeared in the New Yorker, the Saturday Evening Post, Playboy, and numerous literary journals.

Brodeur’s first marriage to Malabar Schleiter ended in divorce, as did a brief second marriage to Margaret Staats. His third wife, Milane Christiansen, a bookstore owner, died in 2013.

He is survived by his son, Stephen Brodeur of Orleans and Boston, a telecommunications entrepreneur and inventor, and his daughter, Adrienne of Orleans and Cambridge, a novelist, memoirist, founding editor of the fiction magazine Zoetrope, and executive director of the Aspen Institute’s Aspen Words Program. Both children are from his first marriage. He also leaves three grandchildren and a sister, Valjeanne Paxton of Switzerland. His younger brother, David, died in 2019.

Brodeur was an ardent saltwater fly fisherman who lived most of the year in Truro in a modern house made of concrete and glass that contained a large collection of paintings by New York and Cape Cod artists.

In a memoir titled Secrets: A Writer in the Cold War, he noted that he had been called an alarmist, a scaremonger, a sensationalist, and an environmental terrorist by officials of the industries he had exposed for having endangered public health. “The fact is I am none of those,” he said. “I am simply a writer who worked for a magazine during a time when its editors believed that public health issues should be written about at length and in depth.”

The last article to carry Brodeur’s byline in the New Yorker was a tribute to Rachel Carson, whose seminal Silent Spring was first published in its pages.