There is a spot in Robert Jackson’s family home in Guilford, Conn. fondly referred to as “the Russian wall” because it is covered with historical photographs of great 19th-century writers: Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Pushkin, Gogol, Turgenev. Mixed in with those photographs are others, taken by Jackson himself, of 20th-century scholars, critics, and philosophers of Russian literature and culture.

Among the latter group is Mikhail Bakhtin, perhaps the most significant Russian writer on literature, ethics, and the philosophy of language. Bakhtin was anti-theoretical, more interested in how language lives in human experience than abstract concepts about its structure.

When Jackson visited Moscow in February 1975, his Russian colleagues brought him to Bakhtin’s apartment, which had become a place of pilgrimage for Bakhtin’s Western acolytes. In an unpublished autobiographical fragment, Jackson wrote: “I held to no critical theory but was deeply interested in the moral, religious and philosophical issues that lay at the root of Russian literature and culture.” The same could be said of Bakhtin.

Bakhtin died two weeks after Jackson’s visit. His photograph on Jackson’s Russian wall is not an abstraction; it is a physical marker of the interaction between two illustrious human beings.

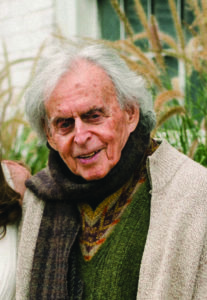

Robert Louis Jackson died at Yale New Haven Hospital on May 3, 2022. The cause of death, confirmed by his daughter Kathy, was an aneurism. He was 98.

Jackson was born on Nov. 10, 1923 in New York City. His father, Eugene Jackson, was a linguist and a socialist who founded the New York City Teachers’ Union Local 5. His mother, Ella (Fred) Jackson, was a painter and an art teacher. They named their son after Robert Louis Stevenson.

As a student at the Walden School on 88th Street in Manhattan, Jackson was taught by the poet Sherwood Trask, whose “poetic temperament,” Jackson wrote years later, had an “impact on me beyond measure.” That influence fed a lifelong idealism that animated Jackson’s scholarship and teaching.

After graduating from Walden in 1941, Jackson enrolled at Cornell University, where he majored in Russian language and literature, at that time a new and rare area of study. He graduated in 1944, a year early.

For a year he worked for the War Dept. on a Russian-English, English-Russian military dictionary, the first of its kind. After World War II ended he joined the Merchant Marine and traveled widely. But he especially relished an assignment to navigate the Mississippi River, where he could follow in the tracks of his beloved Mark Twain.

In 1946, he entered the Slavic dept. at Columbia University, where he earned his M.A. and a certificate from the Russian Institute in 1948. He then took a job as a translator and editor of the Current Digest of the Soviet Press, a journal sponsored by the American Council of Learned Societies. There he met Elizabeth Gillette in 1950.

He and Elizabeth, who was the painter known as Leslie Jackson, married in Mexico City in 1951. According to Kathy, “He thought her a beautiful person — and she was — and he profoundly valued what she did as artist and poet.”

Jackson entered the program in Slavic languages at the University of California, Berkeley, where he completed his Ph.D. in 1953. There were almost no academic jobs in Russian studies, so he accepted a one-year appointment at Yale in 1954. He retired from Yale 48 years later.

Jackson’s career at Yale was nothing short of stellar: he rose through the ranks from instructor in Russian in 1954 to B.E. Bensinger Professor of Slavic Languages and Literature in 1991. In addition to publishing six monographs, primarily on Dostoevsky and Chekhov, with an emphasis on their ethical and spiritual concerns, he edited seven other books and four special issues of major journals and he published 118 journal articles.

At Yale, Jackson wrote, “I had the freedom to be myself.” Yale was his base for organizing the International Dostoevsky Society, the International Chekhov Society, and the Vyacheslav I. Ivanov Convivium. Jackson also launched the Yale Conferences on Slavic Literature and Culture.

He was named a Guggenheim Fellow in 1967, held a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship in 1974, and received two honorary doctorates, one from Moscow State University in 1994 and the other from Petrozavodsk State University in 2000. Germany also granted him an Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung Fellowship in 1999.

Jackson’s parents bought a house on Fisher Road in Truro in 1949. Kathy fondly recalls three generations of the family spending their summers there, where her father would write and her mother would paint. Robert was, she said, “a very visual person.” He served as president of the Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill from 2000 to 2004.

He was, Kathy continued, “an articulate defender of Castle Hill” and “a passionate advocate for the purchase of Edgewood Farm.”

“I wasn’t a born teacher,” Jackson once wrote, but he was a great one. In a tribute posted on Yale’s website after his retirement in 2002, it was noted that he had supervised more doctoral students than anyone in his department. Many of those students, such as Caryl Emerson, Gary Saul Morson, Robin Miller, and Bill Todd, have become acclaimed scholars in Russian literary studies.

Because, as Jackson said, “I was carried away, I was myself, I had convictions and beliefs,” his teaching was a deeply human and humane endeavor. In a birthday tribute, Susanne Fusso, professor of 19th-century Russian literature at Wesleyan University, quoted Jackson on how his teaching looked to him retrospectively.

“It is frightening,” Jackson said, “to realize how important teaching is to writing! You are forced to think and to formulate things clearly, and to ask many questions and to cope with ‘answers’ that raise more questions. And you must do this on time — not postpone till next month.”

Indeed, Jackson did not postpone his last work. Before his death he finished another book, Essays on Anton P. Chekhov: Close Readings by Robert Louis Jackson, edited by Cathy Popkin, with an introduction by Robin Miller, to be published by Academic Studies Press. The book, Miller wrote in an email, “is quite extraordinary.”

Jackson is survived by his daughters, Emily Robin Jackson and husband Haynes Horne of Birmingham, Ala. and Kathy Ellen Jackson of Truro; grandchildren Emily Jeffries and husband Graham of Rockland, Maine, Jesse McDaniel and husband Ben of Hartford, Conn., Ella Gillette Horne and husband Derek Holmes of Birmingham, Ala., Jackson Horne of Easthampton, and Sumaia Jackson Martins of Santa Cruz, Calif.; and great-grandchildren Robin Oakley Jeffries of Rockland, Maine and Iris Elizabeth Holmes of Birmingham, Ala.

Memorial services for the family and at Yale have not yet been announced.