After 30 years of military service, Col. Paul Trahan was supposed to retire on Sept. 11, 2001. He reported to duty at the Pentagon that morning, but at 9:37 a.m. American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the building, killing 125 plus everyone on the plane.

“Men and women from within the devastated area — themselves directly threatened by fire, smoke, and explosive force — provided the leadership, encouragement, and physical assistance that enabled hundreds of shaken and injured people to escape death,” according to a 2007 Defense Dept. report.

Paul was one of those who rescued survivors and recovered the dead, said his husband, Matt Kelley, this week.

Paul P. Trahan died at home in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan on April 21, 2022. The cause, confirmed by Kelley, was prostate cancer. He was 73.

Paul did retire on Oct. 1, 2001, with some regret, because the memory of 9/11 was still so raw. Soon after, he was awarded the Presidential Legion of Merit for his heroism on that day and for his years of service to the country.

The only son among Wilfred and Mary (Degnan) Trahan’s four children, Paul was born in Eastham on Dec. 21, 1948. He attended local schools but finished high school at the New York Military Academy in Cornwall-on-Hudson in 1966.

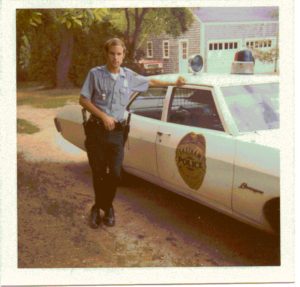

While studying at Norwich University in Vermont, Paul returned to Eastham each summer to work in the police department, where he was employed full-time after graduation in 1971. Later that year, he began his military career.

He earned a master’s degree in social sciences from Pacific Lutheran University in 1980 and attended the U.S. Air Force Command Staff College in 1984-85 and the National War College in 1992-93. He was promoted to colonel in 1994.

Paul’s specialty was armor. He served as the tank company commander at Fort Benning, Ga. and later commanded the Combat Experimentation Battalion at Fort Hunter Liggett in California, training tank units in the high desert.

He served as a military police officer and as a nuclear weapons inspector under the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty in the Soviet Union. On that assignment, he discovered that L.L. Bean’s arctic parka was powerless against Russian winters and learned to appreciate Russian sable.

As a unit commander for NATO in Naples, Italy during the Bosnian war, Paul lived on Via Posillipo, overlooking the bay; he loved visiting the beaches of Capri during time off. Naples, he said, was his favorite overseas deployment.

Paul earned 16 citations for meritorious service, achievement, and deployments. His diplomatic skills led to his appointment as a White House aide during the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations. He became a trusted sounding board in informal conversation with the presidents late in the evening after social events. He was particularly close to Ronald and Nancy Reagan. His last assignment was chief of the Intelligence Oversight Division at the Pentagon.

Paul’s bravery on Sept. 11 was of a piece with his Army service writ large; humanity and empathy were essential qualities for him, especially but not only in the context of military life. He was, Matt said, “genuine to the core.” In retirement, he drew together friends old and new, military and civilian, in a community that affirmed the value of every life.

The doors were open to everyone at Paul’s house in Alexandria, Va.

“His ‘orphanage’ on Ashwood Drive, from which I graduated, was legendary,” wrote Jim Baker in a social media post. “While I was still in the process of coming out and serving in the military under Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, I didn’t feel like I belonged anywhere. I was lost and felt profoundly alone. Like some sort of guardian angel, Paul offered me unconditional kindness, even though he hardly knew me. There was no transaction to be made — just boundless generosity.”

Paul’s understanding of his own sexuality did not become clear until six or seven years into his military career, said Matt. He did not want to be defined by his sexuality, but he was serving at a time when military rules would. So, he found ways to serve his country with absolute fidelity while nurturing personal relationships built on understanding and care.

Paul supported gay colleagues inside and outside the military, including at the Gay Olympics in Australia. He loved skiing in Utah, windsurfing in the Pacific Northwest, mountain biking in California, and camping everywhere.

Paul could fix anything; many considered him their own personal MacGyver. The trunk of his BMW always seemed to contain the tool he needed. He once repaired a blown-out radiator hose with discarded plumbing parts scrounged from a gas station’s waste bin, said Matt.

Every summer, Paul came to visit his family in Eastham and to vacation in Provincetown. That’s where he met Matt Kelley, an architect, in 2000. They became a couple in 2005, moved in together in New York City in 2012, and married in 2019. Paul spent his last 10 years living a quiet, domestic life in the city with Matt.

In addition to his husband, he is survived by his sisters, Carol Trahan of Plymouth and Louise Morris and husband Glenn of Wellfleet; nephew Lt. Cmd. Chris Morris, wife Sally Ma, and sons Finley and Archer of Fernandina Beach, Fla.; and nephew Nick Morris, wife Laura, and daughters Zoey and Hazel of Pembroke.

Paul was predeceased by his sister Connie Trahan.

There will be a memorial service at 11 a.m. on Saturday, May 14 at Evergreen Cemetery in Eastham, followed by a celebration of Paul’s life.

In lieu of flowers, donations in Paul and Connie Trahan’s names can be made to Cape Abilities (capeabilities.org) or to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (mskcc.org).

For online condolences, visit nickersonfunerals.com.

—————

Obituaries in the Independent

The Provincetown Independent publishes obituaries as news stories of abiding interest to the community. There is no charge. Draft obituaries may be submitted to [email protected]. All submissions are subject to editing.