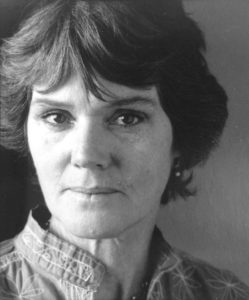

PROVINCETOWN — Elspeth Halvorsen Vevers, an icon of Provincetown’s art community and a resident since the mid-1950s, died peacefully at home on Nov. 17, 2019, her daughters Stephanie and Tabitha holding her hands. She was 90 years old.

She was known for her luminous box constructions, finely wrought from the humblest of materials. Until being diagnosed with mesothelioma a year and a half earlier, she was still working in her studio, taking mile-long walks along the beach, and occasionally seen pruning errant tree branches from atop a weathered ladder. Many referred to her as a true Provincetown original.

Her meditative artworks were featured in the exhibition “Image in the Box: From Cornwell to Contemporary” at Hollis Taggart Galleries, New York in 2008. In 2013 Varujan Boghosian curated a major survey of her most purely spatial work, titled “An Intimate Cosmos,” at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum. He wrote that her works “stand on their own two feet beside Joseph Cornell…. At their core they are very dynamic pieces that call to mind Myron Stout’s totemic works, or Naum Gabo’s … close to god-like work.”

She was something of an alchemist in the studio, transmuting spare and raw materials such as burnished aluminum, glass lenses, hidden mirrors, orbs, shifting sand, and horseshoe crab shells into metaphors for landscape, emotion, and the otherworldly. “When I surrender myself to solving the problems and intricacies of these somewhat labor intensive, architectural constructions,” she wrote, “I find the revival that only ongoing creating can provide…. I strive to create a meditative space in which the viewer may wander.”

Elspeth was born in New York on Feb. 23, 1929 to Colette Finch Pratt, who was from England, and the Norwegian immigrant chemist and inventor Arthur Halvorsen. In her teens her decisive, iconoclastic spirit meant she was not a good fit for a scholarship year at St. Mary’s Episcopal boarding school in Peekskill, N.Y. She was expelled for skiing out of bounds and after curfew on what she called long “bucolic and perfectly innocent” afternoons of rapture.

Her father died not long after she returned home to Purdys, N.Y. in 1944, leaving her mother with four children to support. Wartime austerities were the source of Elspeth’s lifelong commitment to improvisation and thrift, which guided both her resourceful use of materials and her innate desire to leave a small carbon footprint.

After high school Elspeth joined her sister Hildur in New York’s East Village, where she began her studies at the Art Students League and the New School for Social Research. In the summer of 1953, after a year in Paris drawing and painting at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, she visited Monhegan Island in Maine. There she spotted the young Tony Vevers, also just returned from art studies in Europe, as he entered the local dance hall. During their brief island courtship they carved woodcuts printd with ink made from seaweed. By September they were married, living and painting in an unheated loft on New York City’s Delancey Street.

Elspeth and Tony frequented the Cedar Bar, a popular Abstract Expressionist think tank and watering hole in Greenwich Village. In 1955 their first child, Stephanie, was born, and feeling that “New York was no place for an infant,” they decided to move to Provincetown. Milton Avery told them about a winter home on Commercial Street overlooking the harbor, and they were quickly befriended by the community, from the local librarian to Portuguese fishermen, from artists to carpenters. Along with their second child, Tabitha, born in 1957, they became part of the fabric of the town. Elspeth was always up for a gathering of friends over dinner at their home, and was delighted when guests would break into song. She also loved to dance; learning to do the twist at the A-House was a fond memory.

Sympathetic to young artists making their way, Mark Rothko helped them purchase his house and studio on Bradford Street in 1963. The same year, Tony started teaching painting and art history at Purdue University. Settling into winters in Indiana, Elspeth completed a bachelor’s degree with distinction in fine arts in 1969, marking a turn toward black and white photography and ceramic sculpture that would ultimately figure in her assemblage work.

During the summers, as an active member of the artist-run Group Gallery from 1979 to 1988 and co-founder and president of Rising Tide Gallery from 1988 to 1998, she remained focused on being a serious artist. She has been represented by Berta Walker Gallery since 2003. The gallery celebrated her work with a major exhibition in 2018. In a Boston Globe review, Cate McQuaid wrote, “Halvorsen’s surreal box constructions read like poetry: concise, lyrical, and sown with symbols and metaphors that … create odd and tender openings in the viewer’s imagination.”

Elspeth also shared her love of art with generations of children, teaching classes in clay sculpture, freeform assemblage construction, and an introduction to the use of tools. In later years she took great pleasure in encounters with former students or parents who told her how formative those classes were. In her eighties she picked up a video camera to record town events and produced a short documentary about the dramatic launch of the schooner Istar.

Elspeth was a loving mother and wife, fiercely loyal to friends and family. She was predeceased by her husband, Tony Vevers, her sister, Hildur Kehoe, and her brothers, Björn and Robin Halvorsen. She leaves her daughters, Stephanie Vevers of Brooklyn and Provincetown and Tabitha Vevers and husband Daniel Ranalli of Wellfleet and Cambridge, and many nieces and nephews, including Anthony and Jonathan Sherin.

A memorial celebration of Elspeth’s life is being planned. Donations in her memory may be made to the Provincetown Art Association and Museum or to Helping Our Women in Provincetown.