Strangers see me standing next to my telescope on the street in New York or on First Encounter Beach in Eastham and think I might know the answers to any number of astronomy-related questions. “What’s a shooting star?” they ask me. Or “How far away is the Moon?” or “Can you really see Saturn’s rings in that?” (Answers: a speck of comet dust burning up in our atmosphere; 220,000 miles; yes.)

Lately, they’re asking, “What do you think of sending people back to the Moon?” This one’s not an easy question to answer.

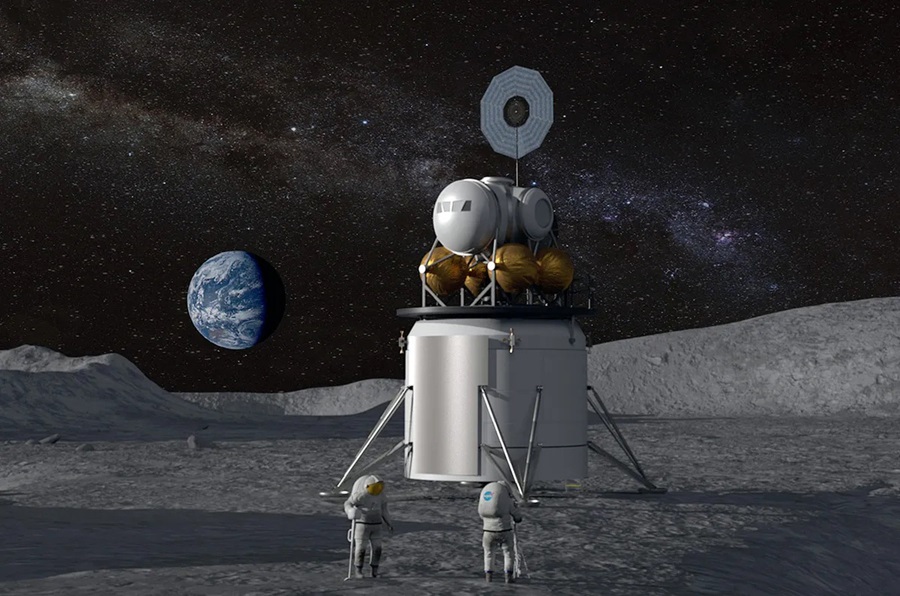

It seems as if every week a private space company launches a rocket and reaches another milestone in its plans for putting people into space. Celebrities and billionaires take joyrides to the edge of space and back. And NASA is inching closer to the first crewed launch of Artemis, the space program that will send astronauts back to the Moon in 2026.

But why? The first astronauts landed on the Moon in 1969; the last in 1972. Is there a compelling reason to return? Couldn’t robot landers explore the lunar surface and transmit scientific data? It’s much cheaper to land a robot than a person. And safer. Getting to the Moon and back is still no easy feat 50 years after Apollo.

One answer is that, while it is cheaper and safer to send robots, an astronaut on the Moon could do more science in five minutes than a robot could in five months. The same is true for any endeavor in space. Our hands, even in a bulky spacesuit, are incredible tools. And humans can adapt themselves and their tools to the unexpected, to the new discovery, not just what the mission set out to accomplish.

I’ve written before about the value of instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope despite its large cost. Or consider the two Voyager spacecraft, launched in 1977 with hopes of at least a five-year mission. They’re still transmitting useful data 47 years later as they hurtle out of the solar system and into the lonely depths of interstellar space.

But the bill for Artemis is expected to exceed $93 billion. Add many billions more for the private companies involved. And the cost is not just counted in money. Space exploration is dangerous. People may die realizing this goal.

Right now, here on Earth, we need billions of dollars, or more likely trillions, dedicated to climate change mitigation, supporting democracy and human rights, and desperately needed breakthroughs in clean energy generation and storage.

So, my answer is that I do not support crewed space exploration. This is difficult for me to say. My childhood bookshelves were filled with books about the Apollo, Gemini, and Mercury programs of the 1960s. I had framed photos of the Apollo 11 and first space shuttle launch on my wall. Famous athletes meant nothing to me, but the names Sheppard, Glenn, Grissom, and Aldrin — all legendary astronauts — meant a great deal. And I dreamed of a future in which people lived in space: I could imagine a straight line from the NASA I knew then to the 23rd-century world of Star Trek, which of course I watched avidly.

Space will wait for us. Send the robots. It’s a good compromise until we sort things out down here.

I’m not alone in thinking this way. But politics and pride seem to have wills of their own. Let’s set aside cynical considerations and take people at their word. Many say that crewed space exploration inspires young people to pursue science and engineering. I certainly agree with that. Or they say exploration is an essential and irrepressible part of human nature. That’s also true, at least for some. Space exploration yields technological innovations that improve people’s lives. There is truth to that as well.

NASA’s space programs of the past 50 years have brought us personal computers, solar power, GPS navigation, defibrillators, and countless plastics, metal alloys, foams, lubricants, and other high-performance materials whose origins most of us never think about. And, of course, Tang. Could we expect new wonders from sending astronauts further into space? Yes. But that’s not the only way to invent new things.

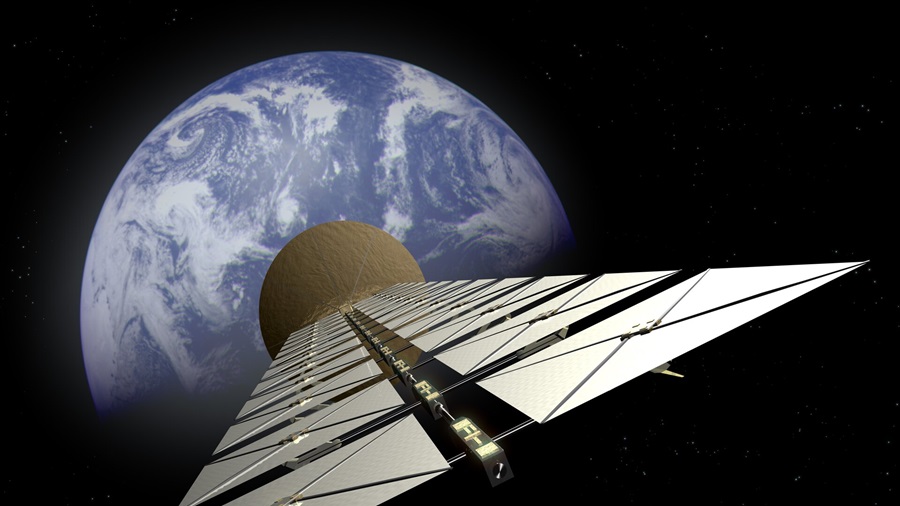

I still see a bright future for humanity in space. I see enormous solar panel grids in orbit, beaming clean, limitless power to receivers on Earth. I imagine production facilities up there, manufacturing useful materials that can be made only in free fall. I see asteroids rich in rare, valuable metals hauled to lunar orbit (by robot spacecraft, naturally) and mined. And I imagine a space elevator transporting people and goods up and down Earth’s gravity well rather than bulky, dangerous, and inefficient chemically powered rockets. Space elevators are an old science fiction idea that I’m sure we’ll see someday. All that’s needed are two or three major breakthroughs in materials engineering.

But that future is not now. As much as it would thrill me to see astronauts on the Moon again, or landing on Mars for the first time, I’d much rather see us roll up our sleeves and dig into the less glorious but critically important work that must be done on Earth. Until that future arrives, you’re welcome to look through my telescope anytime. Clear skies!