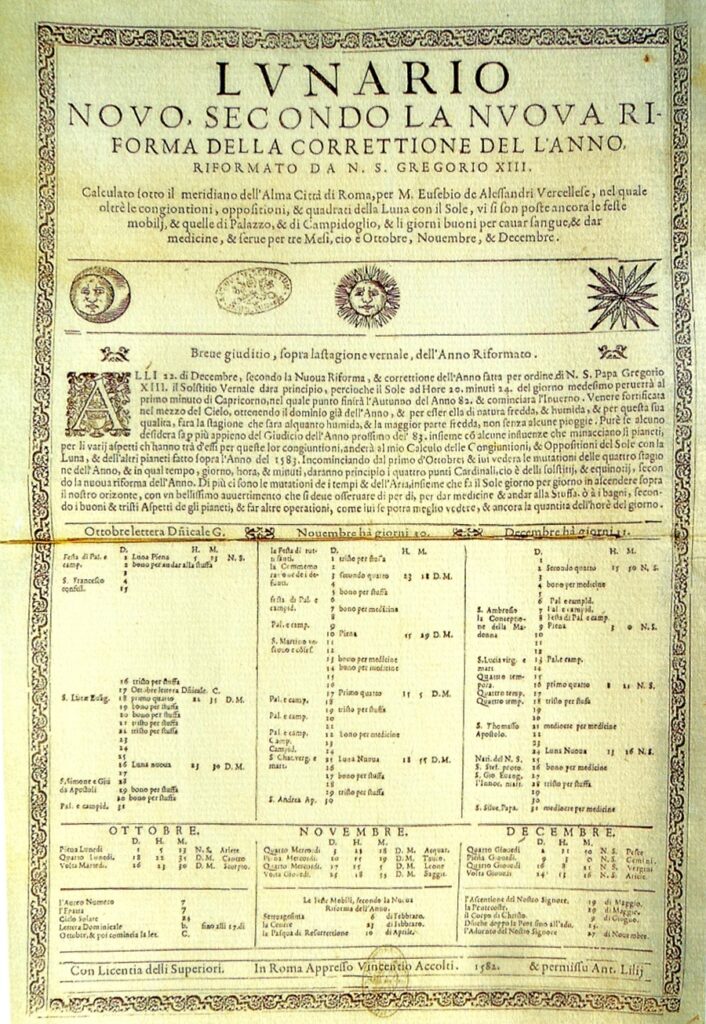

Everybody knows that one day — the time it takes Earth to rotate once around its axis — is 24 hours. And one year — the time it takes Earth to complete one revolution around the Sun — is 365 days. These are nice whole numbers, easy to reckon with in our daily living. Unfortunately, reality is not quite as nice and whole as we might like it to be, and our calendar and day are not perfectly synchronized with the movements of the Earth and Sun. That’s why this year is a leap year — which means we’re granting February an extra day.

Earth travels in an ellipse as it orbits the Sun. One complete orbit equals one solar year. For a closer look at why we need a leap year adjustment, let’s precisely measure the time of a solar year.

The upcoming spring equinox on March 19 makes a convenient starting point, when Earth’s axis of rotation is oriented perpendicular to the Sun. (Our axis wobbles throughout the year, which creates the different seasons, but that’s another story.)

Using some magic space chalk, we mark the position in space that Earth occupies on the spring equinox. Then we start a timer and wait patiently while Earth goes around the Sun. The moment Earth returns to the position we marked with chalk, we stop the timer. The elapsed time is not exactly 365 days. Instead, it’s 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, and 56 seconds.

Why We Leap and When

The nearly six-hour difference between the solar year and our calendar may not seem significant. But over decades and centuries it would add up, disconnecting our holidays from the time of year when we traditionally celebrate them: Halloween would sometimes occur in spring; the Fourth of July would spend time in winter, ruining parades and barbecues; Christmas and Hanukkah would drift continually through the seasons. It’s hard to imagine these holidays of light, meant to bring cheer against the cold winter darkness, falling in the middle of summer, during the longest and warmest days of the year.

Fortunately, the solution is simple. Six extra hours per solar year add up to an error of one 24-hour day every four years. To correct the error, every four years we add one day to our calendar, creating February 29 out of nothing: a leap day.

That extra day corrects the error and brings our calendar back into alignment with the solar year. Problem solved.

But wait. Not quite. We saw before that the discrepancy in the solar year is 11 minutes and 4 seconds short of an even 6 hours.

That makes the leap year correction a slight overcorrection, making our calendar year a little longer than the solar year. It’s the best we can do with whole numbers; the universe felt no need to consult with us when establishing the laws of physics.

But physics-minded people have found a simple enough solution. Leap days occur in every year that is exactly divisible by four (every four years) except if a year is divisible by 100 and not divisible by 400. In that case we skip the leap year. This infrequent fix — in the past 500 years, there was no leap day in 1700, 1800 and 1900, though 2000 had one — corrects for the overcorrection.

We can never have a perfectly synchronized solar year and calendar. But we can dance back and forth, close enough for the seasons and holidays to remain where we like them to be.

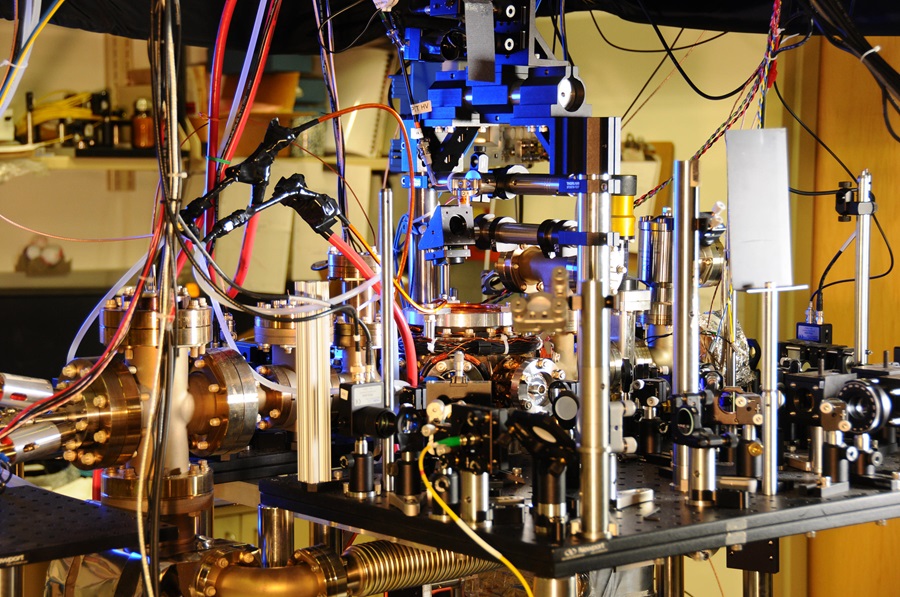

The Atomic Clock

The Earth’s rotation doesn’t exactly work like clockwork either.

Your clock tells you that one day is exactly 24 hours. But Earth’s rotational speed varies slightly depending on where we are in our solar orbit, the current tilt of our axis relative to the Sun, and more orbital factors. Plus, tidal friction from the Moon is slowing our rotation by about 2 milliseconds every year.

These interactive and somewhat unpredictable discrepancies present a more difficult challenge than that of the calendar year. But once again we are fortunate. You may not have heard of them, but the unsung heroes of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), a specialized department of the United Nations, bravely stand between us and utter time chaos.

The ITU manages Coordinated Universal Time (or UTC), the time standard used worldwide.

Precise time synchronization is vitally important for modern telecommunications, the internet, financial markets, science collaboration, the military, and more. The ITU keeps close watch on the various length-of-day discrepancies mentioned earlier. When things get too far out of synchronization, the ITU adds a leap second to UTC, correcting for the accumulated errors.

They add a leap second about once every 19 months, quietly, with little fanfare. Maybe this doesn’t bother us because we perceive time as mutable. Reading a book, we lose track of time. Yet we feel every second in the dentist’s chair.

Meanwhile, our smartphones receive time information from mobile service providers, whose computers in turn get the time from UTC timecode servers. Everything adjusts accordingly. We go about our daily lives unaware of how close we were to a time crisis worthy of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Clear skies!