Our solar system has eight planets, including Earth. Of these, five are visible to the unaided eye: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Uranus and Neptune require a telescope. Of the visible planets, Mercury is the most difficult to see, but July offers Earthlings a good chance to catch it.

Mercury’s proximity to the Sun is what makes it hard to see. Of all the planets, it orbits closest to the Sun at an average distance of 36 million miles. (Contrast that with our own 93 million miles.) This means that, from our point of view looking sunward, Mercury is never far from the Sun’s glare. Imagine standing at a distance and trying to see a lit match beside a bright searchlight. Move the match far enough to the side and you can see it. Move it too close and it vanishes. Astronomers call that horizontal separation elongation. When Mercury is nearest us, or at greatest elongation, as it will be in July, we can see it. It won’t be easy, though. Even at greatest elongation Mercury follows the Sun closely.

Your best chance this summer is just after sunset on July 12, the night of greatest elongation for this apparition of Mercury. You can also try any evening about 10 or 12 days before and after that date. On July 7 you can see Mercury with a nearby crescent moon, a lovely pairing.

To see Mercury, you’ll need a clear view to the west all the way down to the horizon; a bay beach is ideal. Check for the time of sunset. Mercury becomes visible 30 minutes after sunset and remains visible for only about 15 minutes, so don’t wait for dark. Half an hour after sunset, face west and hold out a clenched fist straight in front of you, due west. You’ll use that fist as a measuring device. When held out palm down, your fist marks about 5 degrees of sky. Turn your fist on the heel of your hand and it marks about 10 degrees. Mercury will be a pale pink dot a little north of west, above the glow of the Sun, at somewhere between 0 and 20 degrees of altitude, depending on which night you’re observing.

You probably won’t see Mercury at first because the sky will still be fairly bright, masking the planet. Slowly scan back and forth low in the sky above the glow of the Sun. Mercury will surprise you, suddenly popping into view. Don’t look away or you’ll lose it. It may shimmer in and out of view as you watch, slowly sinking into the obscuring murk close to the horizon. Finally, it will vanish, following the Sun.

Despite Mercury’s elusiveness, Assyrian, Chinese, Indian, and other astronomers of the ancient world knew this planet well. All had names for it and mythological associations. The Babylonians and Greeks both named the planet after their messenger gods, Nabu and Hermes, respectively. The Maya linked Mercury with a mythological owl that was a messenger to the underworld. Note this similarity with Hermes and later the Roman Mercury, who, in addition to their role as divine messengers escorted the souls of the dead to the underworld.

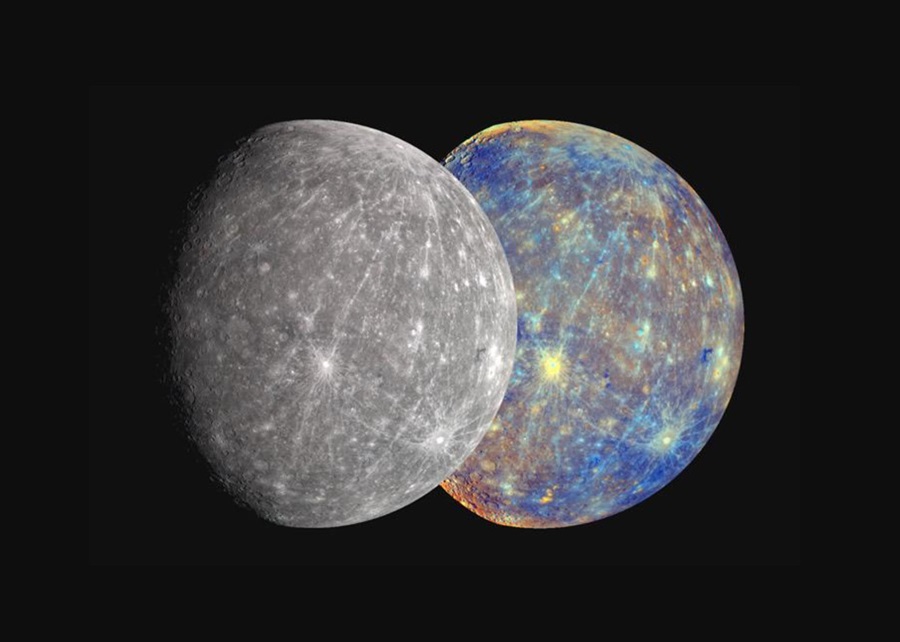

Like Mars, Earth, and Venus, Mercury is a terrestrial planet, which means it’s mostly made of rock and metal. The gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn) and ice giants (Uranus and Neptune) of the outer solar system are many times the size of the terrestrial planets and are mostly atmosphere by volume, though they have solid metallic cores larger than Earth itself.

Mercury’s proximity to the Sun doesn’t just make it hard to observe. It also makes it an extremely unpleasant place to visit (not that anyone has, but imagining it is fun). An enormous sun blazes above a barren rocky surface. There is no atmosphere; intense solar radiation blasted away whatever atmosphere it might have once had long ago. Mercury rotates slowly for a planet its size: one Mercurial day equals 59 Earth days. One result of this slow rotation is that temperatures on the Sun-facing side can climb to 800° F. During the long night on the other side, temperatures plummet to minus 280 degrees.

After Pluto’s outrageous demotion to “dwarf planet” in 2006, Mercury became the smallest planet in our solar system. At 3,000 miles in diameter, Mercury is a little more than one-third Earth’s diameter of 7,900 miles.

It’s small, but Mercury has a lot of personality. The other naked-eye planets are easy to see. They hang around for weeks or months at a time. Some shine astonishingly brightly (Venus is such a show-off). They have rich colors: deep red Mars, golden-white Jupiter. And they conveniently place themselves high in the sky long after sunset or well before dawn.

Mercury is and does none of these things. It’s a pale little speck, nearly lost in the twilight sky, so low that any tree will hide it, and it’s gone before night falls. Mercury is irreverent. It teases. It laughs at us, glimmering in the sky and coming and going as it pleases. I’ve chased this divine trickster many times. And each time I’ve caught sight of it, I laugh, too.

“There you are,” I always say. “I see you. You’re not getting away this time.”

Then, just as passersby begin to glance suspiciously at me, Mercury is gone.