In the very first issue of the Independent, I wrote about Jupiter and Saturn, which were prominently in view at the time. After making their way across the sky and disappearing briefly during winter, Jupiter and Saturn are once again visible, marking one happy anniversary of watching the night sky.

The two planets are easy to find. Step outside about an hour after sunset, face south, and look up. Jupiter is the very bright star that you’ll see shining with a rich, golden-white light. To its left is a dimmer, reddish-gold star. That’s Saturn. The two giant planets are a lovely sight together, and right now they share the evening sky with a smaller sibling — Mars. It’s also easy to find.

Turn to the east and look for a bright red star low in the sky. That’s Mars. Contrast its color with Jupiter and Saturn; it really is the red planet. (Mars is rising earlier each night. In early October, look for it a little higher in the sky; late at night, or after sunset in late October, look for it even higher.)

Why is Mars red? The rocks and dust of the Martian surface contain a lot of iron. When iron is exposed to oxygen under certain conditions, they can bond, forming iron oxide — which we Earthlings call rust. Iron oxide molecules are just the right size to absorb blue and green wavelengths of light, and to reflect red, thus the rusty surface of Mars looks red to us.

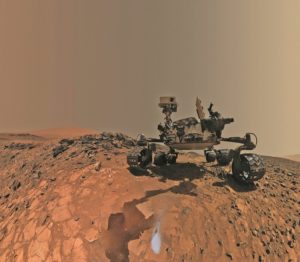

Mars is about half the size of Earth. It’s cold (average temperature is -81 degrees F), dry (the surface is drier than any desert on Earth), and has a thin atmosphere (air pressure is less than one percent of Earth’s). The oxidizing of its surface occurred long ago, when Mars was a very different place. Scientists studying data from orbiting spacecraft, landers, and rovers have found evidence of ancient shorelines, water-carved canyons, and river channels; oceans may have covered a third of its surface, and its atmosphere was likely thicker and warmer. From space, Mars might have looked a little like Earth. It might even have had life.

How did Mars go from being a world that might have fostered life to the desiccated frozen wasteland that we see today? There is evidence that the earlier warm, wet Mars had a global magnetic field, like Earth does, which would have protected its atmosphere and surface from solar radiation, as ours does. Earth’s magnetic field is generated by a dynamo effect deep within our planet: the motion of molten iron in the outer core creates electric current; where there’s an electric current, there’s a magnetic field.

The same phenomenon would have generated the magnetic field of Mars. But for reasons we don’t yet understand, the Martian dynamo shut down billions of years ago. The magnetic field vanished. Solar radiation gradually stripped away much of the atmosphere, the air thinned and cooled, and the water froze. It’s now locked away in polar ice caps and subsurface ice.

If life once existed on Mars, it might have adapted to the harsh changes in the climate and survived. Extremophiles here on Earth (species found in extreme environments, such as under glaciers or in hot springs) continue to surprise scientists with their toughness and adaptability. NASA and other space agencies continue to look for evidence of past or present Martian life.

If any Martian life did survive, it might be found deep underground — that’s prime real estate on Mars these days — protected from radiation and toxic compounds in the topsoil, and where there is likely water ice. Any such life might be something similar to bacteria or algae: primitive, simple, and unlikely to mount an invasion of Earth.

Earth and Mars make their closest approach to each other every 26 months. The next occurrence is coming up soon, on Oct. 6, when the distance between us and Mars will be 38,568,00 miles. Every night leading up to that date, Mars will be a little brighter as we draw nearer.

Don’t worry about binoculars or a telescope — unless you have a very large telescope and a very clear night, Mars tends to be an underwhelming sight in the eyepiece. For most of us, it’s best seen with the unaided eye and a little awareness of its rusty red surface and long history. Sometimes I like to imagine Mars as it might have been once — not red, but a blue-white star in our ancient sky. I like to imagine what secrets it still holds, which we may yet discover. Clear skies!