Greetings from sunny, warm Tortola — a place my mate and I love so much we visit twice a year. I often write about the challenges fishermen face in our waters. Well, I can’t help being curious about what the rewards and difficulties are in other places.

The first thing one notices on the water here is that there are no big commercial trawlers to be seen. Commercial fishing and lobstering are mostly done by small boats, some of which look questionable in terms of seaworthiness.

There are no middlemen fishmongers to speak of: the fishermen sell their catches to restaurants directly or sell to home cooks from ice-filled coolers in the backs of their trucks on the roadside. They mostly catch mahi, wahoo, snapper, and grouper, but sometimes they catch tuna as well.

Despite the abundance of fish in the shallower reefs around the island, fishermen mostly work in the deeper blue waters at some distance from the shore. That’s because many tropical reef fish have ciguatoxin in their bodies, which can cause ciguatera poisoning. Blue-water fish don’t accumulate ciguatoxin and are safe to eat.

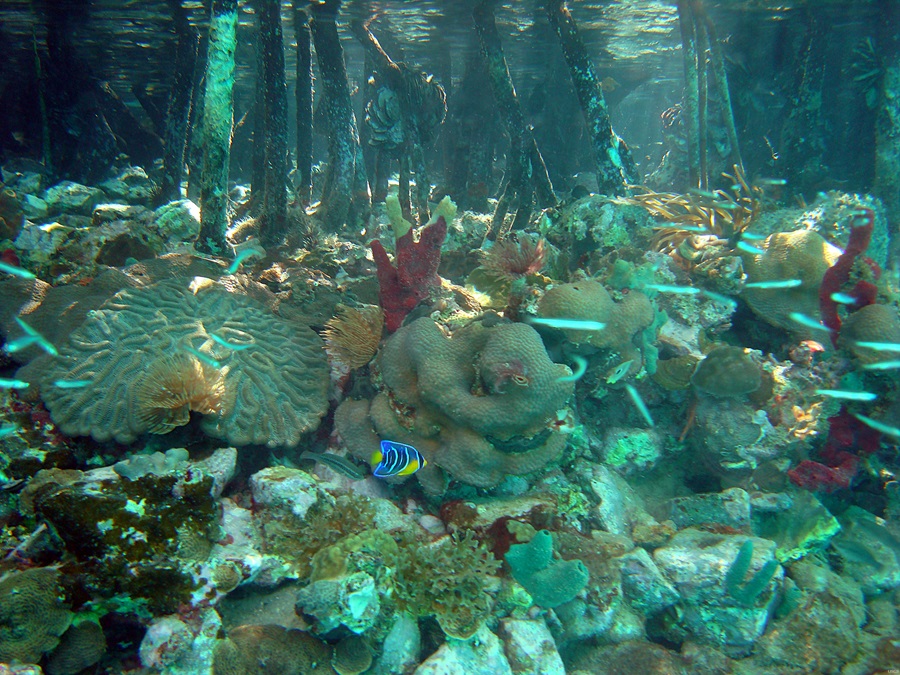

The toxins are naturally occurring: sea plants called dinoflagellates, which grow on coral reefs, produce them. The dinoflagellates are a food source for many small bottom-feeding reef fish. And when these fish are eaten by larger fish in the food chain, the ciguatoxins accumulate and become progressively more concentrated.

Barracuda, grouper, snapper, and parrotfish can all be sources of ciguatera poisoning. I know someone who got it from eating a barracuda, and let me tell you, it was no joke. It took this person years to finally feel better. There is no cure, and you can’t kill the toxins by cooking the fish — they persist even at high temperatures.

It’s no secret that the coral reefs themselves are dying. I snorkel and scuba dive here, and the change that I’ve seen over the years as the warming water bleaches the reefs and turns vibrant colors into a muted white and gray seascape is depressing. Sea life on the reefs is in turn decreasing, too.

As far as fisheries management goes, there isn’t much of that here, for good and for bad. The islanders are worried about the overfishing of parrotfish. These fish use a parrot-like beak to scrape algae off the rocks and dead corals, grinding up the coral as they go in their pharyngeal mill (a grinding apparatus in their throats). The parrotfish eventually excrete the ground-up coral as fine white sand. So, yes, those beautiful soft white beaches we all love in the Caribbean are made up of a fair amount of dried parrotfish poop. One large parrotfish can make up to a half ton of sand every year.

The concern about overfishing is not just about the beauty of the beaches. The more sand on the beaches, the better the protection from storms.

The rest of the fisheries down here appear to be in pretty good shape, with the absence of massive trawlers undoubtedly helping. At the end of the day, fishermen in these islands are no different from the ones at home — salt of the earth, hardworking men and women who farm the seas and provide our food. But it seems to me their lives are much simpler than those of commercial fishermen back home — and in some ways better for it.

I haven’t seen any of our humpbacks here yet, but they are on their way to breed and give birth and should be arriving soon. Nature’s clock ensures that all these animals go where they need to go, when they need to go, and hopefully we don’t mess with nature to the point where even that gets disturbed.