The semiannual changing of the clocks couldn’t come at a worse time — just after the fishing has slowed to a near stop, when the days are getting colder and what sunlight there is seems anemic compared to the bright days of spring.

I go through the early fall thinking I’m prepared for the inevitable only to be shocked and saddened every time daylight saving time finally comes to an end.

I hate this turning back of time not only because it alters the cosmic equation of light and darkness or even because it’s a pointless relic of a bygone era. I loathe it for the way it rudely interrupts our normal biorhythms for no apparent reason, like a slap in the face right in the middle of a seemingly genial chat.

For a fisherman, the sudden dimming of the afternoon light adds insult to injury: not only is fishing on the wane, but things will get worse, at least until the state begins restocking our ponds with trout in early March.

There’s a misconception that fishermen become hooked to the sport because of the thrill of landing a fish. That might be the initial lure, but what turns an enthusiast into a devotee is not so much the interaction with one’s quarry as it is the deepening understanding and appreciation of nature. Fishing has a way of revealing the beauty and complexity of the world in which we live. And it offers tranquility.

Chatting with fellow fishermen while stalking the beach or wading in a river or fishing from a boat, I hear them say, “Isn’t this just beautiful?” rather than talking about their catch. Trout don’t live in ugly places.

While winter’s arrival leaves a veritable hole in my being, it’s one I know how to fill.

I had been out to the ocean beaches looking for whales and seabirds, a rewarding investment of time in November, when the whales are feeding close to shore, and rafts of seabirds carpet the sea and grace the sky. Then, out of habit, I went down to Wellfleet Harbor for a peek at the water where, every fall, the bait piles up in Chipman’s Cove and the mouth of Duck Creek, attracting all manner of predators.

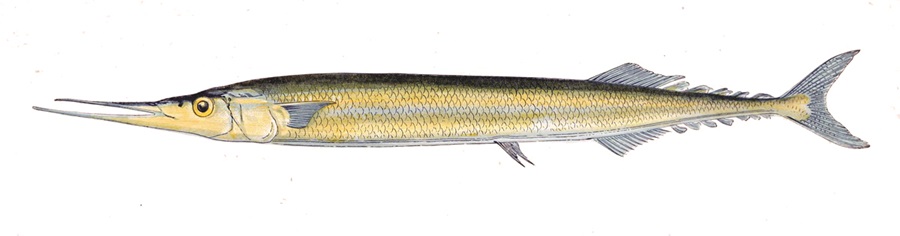

Sure enough, when I reached the town pier there were large flocks of cormorants and small gulls diving in the channel, surrounded by several harbor seals. The feeding was so frenetic that I wondered if the small silversides were being driven to the surface by larger fish. But after a few minutes I saw the birds were feeding on a needlefish called Atlantic saury.

This slender 6- to 9-inch visitor arrives regularly in early to mid-November, sometimes in schools so large that seabirds are attracted by the thousands. They seem to come in only after the bass, bluefish, and tuna have migrated south. But I found I was glad the commotion wasn’t due to a remnant school of large bass. That nixed any temptation to return home for my rods, already in their winter racks.

As I watched the feeding frenzy, I realized I had turned the corner in the process of winterizing my spirit. I was content to simply watch the fish, birds, and seals. I knew, too, that even if there had been big bass off the pier, my fishing rods would probably have been more of a liability than an asset that day. After seven months of hard use, my lines are sorely in need of replacement. I also have rod eyelets to replace, reel seats that need repair, and reels requiring disassembly, cleaning, and oiling.

In the short, cold days ahead, serenity awaits me at the dining room table near the wood stove, fixing my gear, or at my work bench tying new bucktail hooks for spring.

There is solace, too, in knowing that while spring is still four months away, the light begins returning just five short weeks from now.