PROVINCETOWN — The public leasing contest for eight dune shacks on the windswept back shore of Provincetown and Truro that began on May 1, 2023 has nearly come to an end.

After taking 10 months to review hundreds of applications for 10-year leases for the rustic structures, the National Park Service issued its last selection letter, for the Peg Watson shack in the Cape Cod National Seashore, on May 3.

Laurie Schecter, who has spent her summers in the Watson shack since winning a long-term lease for the disintegrating structure in 1993, won the competition to negotiate another 10-year lease.

In late March, Josh Zacharias and Kaimi Rose Lum were selected to negotiate a lease for the Jones shack, which they have helped care for since Zacharias’s stepfather, Scott Dunn, won a long-term lease for it in the same 1993 contest. Zacharias had been a named caretaker in Dunn’s lease, and after Dunn died in 2011 the Park Service signed a series of one-year use permits with Zacharias and Lum.

These selections fit a pattern that emerged last winter, when either the current occupants of the dune shacks or groups that included their children were awarded the right to negotiate leases for most of the shacks.

The exception was the Adams shack, whose longtime occupants Marcia Adams, 94, and her daughter Sally Adams withdrew their application in October after becoming frustrated by the Park Service’s shifting deadlines.

The dune shack contest had created controversy over the summer — including letters to the Park Service from U.S. senators Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey and a front-page story in the New York Times — largely because of a provision allowing applicants to bid an unlimited amount of extra rent to “enhance the competitiveness of their submission.”

That provision had not been included in the agency’s prior published plans for the leasing contest, and it raised the specter of wealthy applicants being able to displace longtime dune shack dwellers with cash — a possibility that the senators called “a catastrophic affront” to the cultural history of the dune shacks as a place of reflection and retreat.

Ultimately, however, experience appears to have outweighed any outsize offers of rent money.

Schecter said she offered a couple of hundred dollars more than the $4,732 per year the Park Service was asking for the Watson shack — “I went for a round number,” she said — and Lum said she had offered a bit more than the stated rent for the Jones shack. Both said that their applications emphasized their knowledge of the dune shack and their ability to maintain it.

The Watson Shack

Margaret “Peg” Watson had once lived year-round in her dune shack, but when she died in 1972 it was left in the care of “Dune Charlie” Schmid, who lived in another shack farther east.

When Schmid died in 1984, Cape Cod National Seashore Supt. Herb Olsen ordered his shack demolished within days. Olsen had been preparing to demolish Watson’s shack and that of Leo Fleurant, who also died in 1984, when he told a December 1985 meeting of the Cape Cod National Seashore Advisory Commission that he would delay those demolitions until a historic inventory had been completed, according to reports in the Provincetown Advocate and Boston Globe.

The Park Service’s Historic Structure Inventory from 1987, which the agency produced in response to a records request from the Independent, found that all 18 dune shacks in the National Seashore had “no historical significance” and could be demolished.

The Keeper of the National Register did not accept the Park Service’s conclusion, however, and found them eligible for protection in May 1989.

“That’s how these vacant shacks came to be put up for applications in 1993,” said Laurie Schecter’s sister, Julie Schecter, a founder of the Peaked Hill Trust, who had advocated for the preservation of the shacks. “They had been planning to demolish them, but now that they had historic value, they needed to find people who could keep them up.”

The Watson shack, Fleurant shack, and Jones shack were included in one leasing contest in 1993, and the Park Service received fewer than 20 applications, said Schecter.

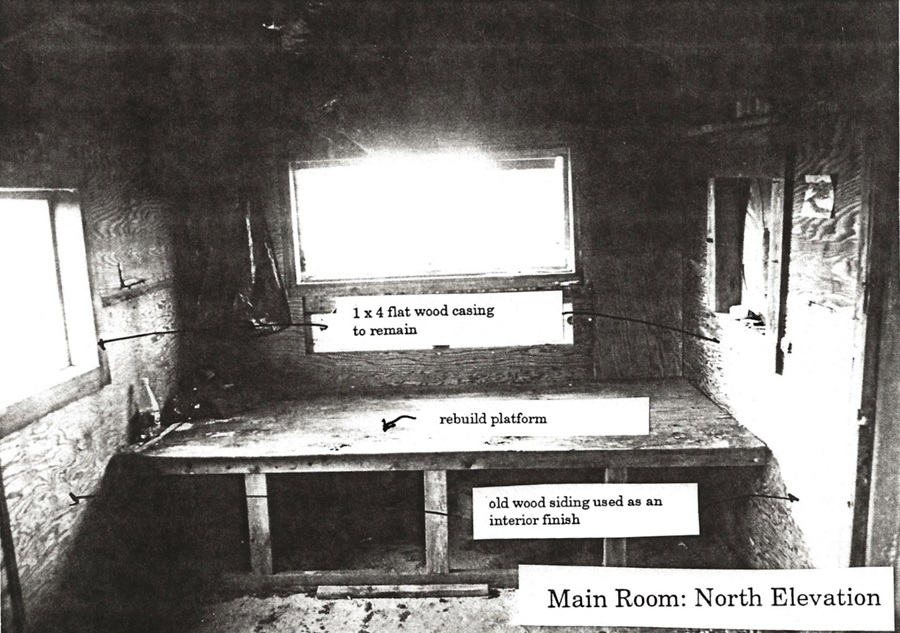

When Laurie Schecter and her husband, Gary Isaacson, won a long-term lease for the Watson shack, the building was an empty, leaky shell, Schecter said.

“There’s nothing in that shack that we didn’t have to rebuild,” she said. “The four walls, the ceiling, the floor — we even put in the wood-burning stove.”

The couple had built a similar rustic shack in Michigan, and they had friends who had done backwoods construction as well. They raised the shack out of several feet of encroaching sand in 2004.

“We have the beams and posts set up now so you don’t have to install new posts — you just detach the beams from the posts, jack them up, and reattach them again,” Schecter said. “We have done two other lifts since 2004, but they were so much easier and simpler than that first one.”

Schecter and Isaacson moved from Sudbury to Florida in 1999, and Isaacson died in 2009. Schecter still spends summers in the Watson shack, though friends help her open it in spring and close it in fall, she said.

The Jones Shack

Josh Zacharias grew up in Provincetown’s East End in a cluster of families that spent their free time in the dunes, he said. The Del Deo, Tasha, and Malicoat families all lived nearby, and Frank Milby, who had Zara Ofsevit’s dune shack then, lived across the street.

“I was friends with Frank Milby’s kids, and we would go out to Zara’s shack and pick blueberries, and Frank would make French crepes with blueberries and yogurt,” said Zacharias.

“Now we’re showing our kids how to do things that Josh did when he was young,” said Lum.

By the time Zacharias graduated from Provincetown High School in 1988, Scott Dunn and Zacharias’s mother, Lynda, had separated. In 1993, Dunn and his wife, Marsha, applied together for the Jones shack, with Zacharias as their helper.

“Scott and Marsha lived in Wellfleet by then, and I would help them open the shack and do maintenance work all through the spring before they moved into it in June or July,” Zacharias said. “You can’t drive right to the shack anymore — there’s a 40-foot sand bowl and the route is just too steep — and that makes it harder to get supplies to the shack than it used to be.”

Lum and Zacharias married in 2005 and are raising their daughters, Zoe and Maisie, in Eastham. Going to the dune shack keeps the girls connected to their father’s childhood in the backwoods of Provincetown, Lum said.

When Scott Dunn died in 2011, his ashes were scattered at the Jones shack. The Park Service had just completed its Dune Shack Preservation and Use Plan, which details how “transitions” such as deaths should be managed, so the agency had no problem writing temporary use permits for Zacharias in accordance with the Use Plan, Lum said.

Editor’s note: Because of a reporting error, an earlier version of this article, published in print on May 16, gave an incorrect date for the death of “Dune Charlie” Schmid. It was 1984, not 1985.