Happy days are here again: the commercial bluefin tuna season has reopened as of Oct. 1. The quota, at 117 metric tons, is set pretty low, so if the bite is decent, I think this fishery will close fairly swiftly.

These fish aren’t commanding the sky-high prices on the international market that they used to. The market seems to be consistently flooded with tuna, and with the Japanese ramping up bluefin fish farming, prices will more than likely stay low. I imagine our bluefin tuna will become more of a domestic product than an exported one.

There seem to be some giants in the bay and down back by Peaked Hill, and when this relentless north-to-northeast wind finally subsides, we may get a clearer picture of how our local tuna fishing will go.

Bluefishing remains surprisingly good despite the colder water this persistent northerly wind has brought. The fish are camped on the ocean side in the usual places around Peaked Hill and tight to the beach from the Race Point Ranger Station to Head of the Meadow. They have made some brief appearances in the bay here, but the south end of Cape Cod Bay has been far more consistently productive.

There are still some striped bass around, although their numbers are dwindling as they begin their sojourn back to their winter areas, first around the Chesapeake Bay and the Hudson River, then to points south.

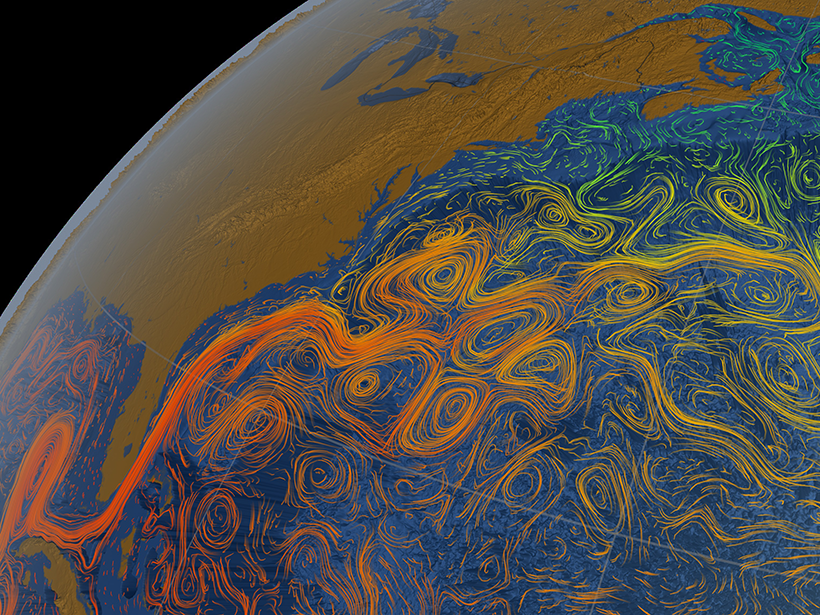

A rather disturbing report was released on Sept. 25 by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution regarding the status of the Gulf Stream. The current is weakening significantly, it says, based on a new analysis by WHOI scientists led by Chris Piecuch at Woods Hole, who worked with researchers from the University of Miami to look at four decades of data from the Florida Straits. The study analyzed a wide array of measurements of the volume of seawater moved through the area during that period — its so-called transport. What they discovered was that the Gulf Stream transport has decreased by roughly 4 percent over the past few decades, which is the first “conclusive unambiguous observational evidence” of a slowing current.

If this is truly the case, it will have profound consequences to our region’s weather systems. When the Gulf Stream changes, so does the climate. And although the specific reasons for the change were not part of this most recent study, the analysis shows this isn’t a random event. Global warming is the likely cause.

The frightening part is how little we know about what the regional and global results of this change will be. What we do know is that this major arterial ocean current is a critical component of the planet’s climate, influencing not only extreme weather events but average air and water temperatures and levels of rainfall as well.

Without the full-on effect of the Gulf Stream here — it brings warm water this way before turning toward the British Isles — our ocean and bay water temperatures could become much colder, a reversal of the warming pattern we have been seeing. The Gulf Stream delivers nutrients on its wide path as well. Who knows what the loss of that could mean in our waters?

And this is not settled science, but with fresh water streaming into the ocean from the melting Greenland Ice Cap, a researcher at the University of Copenhagen has gone so far as to project the Gulf Stream could come to a halt anytime between 2025 and 2050.

What’s undeniable is that the reach of changes in the Gulf Stream will be as big as the ocean is. The WHOI study’s coauthor, oceanographer Lisa Beal of the University of Miami, put it this way: “The Gulf Stream is a vital artery of the ocean’s circulation, and so the ramifications of its weakening are global.”