PROVINCETOWN — Last month’s special town meeting primarily concerned the town’s sewer expansion program, but there was one significant outlier on the warrant: Article 2, seeking $1.75 million of Land Bank funds to purchase 1.9 acres at the far east end of Commercial Street.

The Land Bank was expiring, open space committee Chair Dennis Minsky told the voters that night, and this purchase would be the last major use of its funds. The article passed unanimously, and the room gave Minsky a warm round of applause.

The Land Bank is expiring because of the legislation that created it in 1998, according to Mark Robinson, executive director of the Cape Cod Compact of Conservation Trusts, which for decades has advised towns on how to create and maintain conservation land.

That legislation came out of a political compromise after the towns of Cape Cod sought to emulate Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, each of which had been using a 2-percent real estate transfer tax to purchase land for conservation since the mid-1980s.

“The Land Banks in Nantucket and the Vineyard are actual entities — you can call them, visit their office, and they have a staff that buys properties and manages them,” Robinson says. Cape Cod towns were asking the state to authorize real estate transfer taxes and Land Banks here in the late 1980s, he says, but real estate interests on Cape Cod and in Boston did not want to see such taxes catching on.

The compromise that passed in 1998 created a 3-percent surcharge on all property taxes instead, with the reasoning that open space benefits all taxpayers, Robinson says. The legislation was limited to Cape Cod, and all 15 towns adopted the Land Bank surcharges at their November 1998 elections.

The 3-percent surcharge model did catch on, however, and it became the basis of the state’s Community Preservation Act, which passed in 2000. Thirteen towns on Cape Cod abandoned their Land Bank program in favor of the CPA, which also authorizes a 3-percent surcharge but allows the money to be split among conservation, historic preservation, and affordable housing.

Only Chatham and Provincetown adopted the CPA surcharge while also leaving their Land Bank in place, Robinson said — so, for most of the last 20 years, only Chatham and Provincetown have had publicly funded Land Banks. The legislation authorizing the Land Bank surcharges expired on Jan. 1, 2020.

Over its lifetime, Provincetown’s Land Bank brought in about $9 million to buy land for conservation. The open space committee had public meetings to decide which parcels to buy, and all purchases were approved at town meetings.

Which Land to Buy?

Some of the money has paid for more developed parks. Both the B Street Garden and the Cannery Wharf Park give people access to outdoor spaces that are well worth their price, Minsky says.

“There’s 70 or 80 people that have plots at the B Street Garden,” he says. “We bought that for $180,000 and got a $93,000 state grant, so that’s been wildly successful.”

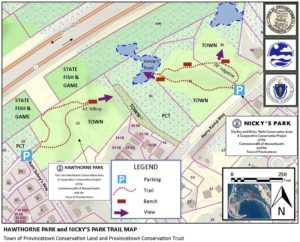

The focus, however, has been on the verdant habitats between Bradford Street and Route 6. Those include the Shank Painter Pond area in the West End; the parcels around Jimmy’s Pond, just north of Harry Kemp Way, in the middle of town; and a rolling series of wet and dry forests that lie along the Old Colony Nature Trail in the East End.

Together, these lands form a greenbelt, Minsky says — a connected chain of forests and wetlands that allow wildlife to move, meet, and reproduce, and allow humans to escape town life and catch their breath.

“The National Seashore is a great resource, a boon for wildlife and people here,” Minsky says. “But it does not include some of the wooded, vegetated, wetland areas that we have here in town.”

William Mullin, the chair of the Provincetown Conservation Trust, also emphasizes the difference between the town’s conservation land and the National Seashore.

“The greenway is very, very important for bird life and other animals because the National Seashore is mostly desiccated dunes,” says Mullin. “A lot of the habitat is along the Old Colony Nature Trail and in the wetlands and woodland around it, much of which is in private ownership.”

The Trust holds the conservation easements on property the town has purchased with Land Bank funds, Mullin says. It also receives donations, often of undevelopable wetlands, from landowners. The town will not use Land Bank funds to buy undevelopable wetlands, Minsky says, but the state has created tax benefits for donating such land for conservation.

At Shank Painter Pond, for instance, the town purchased a 7.5-acre parcel of upland forest that was already approved for five single-family homes from Patrick Patrick’s family for $1.6 million in 1999. A fire hydrant that had already been installed on the land is still visible along what is now a nature trail.

The Patrick family donated the remaining 22-acre parcel, which includes half of Shank Painter Pond and is entirely composed of wetlands, to the Provincetown Conservation Trust the next year.

It’s hard to assess the acquisitions of the Land Bank or the Conservation Trust in isolation, both Minsky and Mullin say. Rather, they are two sides of a joint effort to establish a belt of protected habitat in Provincetown.

With the Land Bank’s funds now exhausted, the open space committee will likely shift its focus to improving access to conservation lands, Minsky says. The most recent purchase at 806-832 Commercial St., for example, can become a route to the eastern end of the Old Colony Nature Trail — with a little planning and a lot of work, that is.

The town often can get AmeriCorps volunteers to do the actual labor, said Conservation Agent Tim Famulare, but the planning and design is largely up to the open space committee.

“We need some more volunteer people who are in love with that aspect of the problem,” Minsky says. “There’s a lot of work to do to help people access these lands.”