PROVINCETOWN — The summer of 2022 has brought a long-awaited but still frustrating event to Cape Cod: a Covid wave that doesn’t include high levels of hospitalization.

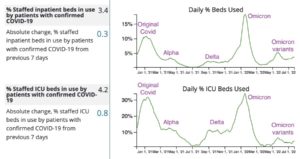

Case numbers are high here — both direct and indirect indicators show that — but for most of the last month, there have been almost no Covid patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) at Cape Cod Hospital. The same is true at Nantucket Cottage Hospital and Martha’s Vineyard Hospital; Falmouth Hospital has typically had one Covid patient in its ICU.

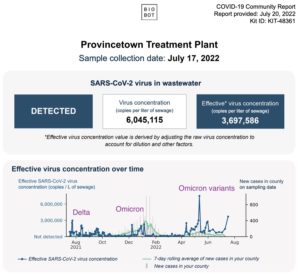

Meanwhile, Provincetown and Nantucket have been reporting Covid-in-wastewater data that are double or triple the numbers from last summer’s Delta wave, and Provincetown actually had the highest wastewater reading in the entire country on May 12.

In prior Covid waves, high case counts were followed by hospitalizations and ICU admissions. State and CDC data both show that is not happening. Paxlovid and other treatments deserve a lot of the credit, according to Dr. Andy Jorgensen of Outer Cape Health Services.

“Having access to this medication has been a tremendous help,” said Jorgensen. “You can go back to the studies that show a dramatic decrease in hospitalization in the populations that received Paxlovid.” He has seen that same effect among the patients he serves, Jorgensen said.

Paxlovid is prescribed to people who have one or more of a long list of potential risk factors for serious Covid, such as cancer, diabetes, or heart disease, as well as those over 65. OCHS has prescribed 382 courses of Paxlovid, according to communications director Gerry Desautels — 250 of which were in the last two months.

Paxlovid must be taken within the first five days of symptoms to be effective, however, so health care providers are telling their at-risk patients to call them early in the course of infection rather than trying to wait the disease out.

“I think people feel a little less afraid because they know treatments are available,” Jorgensen added.

Indeed, the fact that Covid is less lethal is part of why there is so much more of it around. With mask rules, vaccine passports, and mandatory tests for international travel all suspended, the opportunities for viral spread have increased. Public testing is limited — but the Cape and Islands have the highest positive test rates in the state.

People who live here are finding out what a season of less-lethal Covid looks like. It’s not as scary as the ICU, but getting sick during the summer is still hard.

Roxanne Layton is a server at the Red Inn in Provincetown in the summer and a musician who tours with the concert group Mannheim Steamroller in the winter. She got Covid for the first time in June — in the middle of a crosstown move.

“I was sick as a dog, and I tested positive for 12 days,” said Layton. “The hardest part was being sick and not being able to rest.” She said the move was, “one of the hardest things I’ve ever done, physically and emotionally.”

Layton plays the recorder, and she was worried about her lungs as well. “Luckily, when it was done, it was done,” she said. Her lungs have cleared.

At least a few people who get Covid this summer will not be so lucky.

Provincetown resident Cary Bryant was one of the first people to get the Delta variant during last year’s Provincetown cluster. He has been battling the persistent symptoms called Long Covid ever since — in his case, extreme fatigue, loss of coordination, and brain fog.

“I had a pretty mild case in early July last year,” Bryant said, “and I felt OK right after it. But over the summer and into the fall, I had less and less energy and would be overcome by these waves of extreme fatigue, where I really couldn’t do more than lie down.

“Usually, I could do two or three little things — like, do the dishes, or take a shower,” Bryant said. “But that would be all I could do in a day.

“I also think less clearly, I don’t have the memory I had, and just doing simple tasks is harder. I drop things a lot. I’ll drop the same thing three times, even when I’m focusing on it.”

Bryant thinks his condition has been improving. “I felt like I was 90 years old,” said Bryant, who is 57. “Now, I feel like I’m maybe only 78. I can walk into town for dinner, and I stop at every bench on the way home, but I’m not destroyed the next day.”

As recently as April, when he thought his whole life might be like this, Bryant was depressed and angry, he said. Lately he believes he might get better in a few years.

There are few data on Long Covid, partly because what studies do exist use widely diverging definitions of the condition. “Because the definition is still being determined, it will be a while before we have any statistics on that,” said Jorgensen.

The ICUs are largely empty of Covid patients — and that is a welcome change. It hasn’t made Covid easy, though, and a long and mysterious illness remains a grim possibility.