The greens, golds, pinks, and reds of just a few weeks ago have given way to a sepia-toned world, awash in amber, russet, and ash. I pull up to my cottage, step out into the cold, and the silence stuns me. The chatty catbirds and squawking jays are absent. Even the woodpeckers have taken leave. And where are the rabbits? I am alone here, with the winter-knocking wind.

I have missed the peak of my front yard maple. Not yet half turned on my last visit, it’s now bereft of foliage after the recent gale. Withered curls of scarlet and rust cover the front doorstep and collect in the patio corner. My neighbor has raked his yard, gathered his leaves into tidy piles, and bagged them assiduously. I feel a twinge of guilt. I have no plans for yard cleanup on this trip. There will be time enough for that come April.

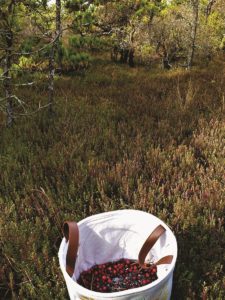

At this time of year, I seek cranberries. Not those of the open bogs, visible from the highway, with their manufactured ditches and flumes and telltale haze of pink. No, the cranberries for me are the ones hidden in the hollows at the tip of the Cape. Humble beneath pitch pines, the cranberry is less lush than the look-alike bearberry.

I’m alone on this gusty morning, but, still I look around as I step off the Province Lands bike path. I don’t want to give away this secret. I walk down a gentle slope, weaving between dormant bushes and dwarf pines. I was shown this spot some years ago by a park ranger and told I could pick a gallon of berries if I wanted. I look for a landmark: a small pine on the path where I must step off and fold myself into the dunes landscape.

Turn right into the sandy clearing, walk south to the wooded edge, bear left and duck under the low branches, look for the short, twisting path of matted pine needles. Before long, I spy it. An unmolested patch of upright, thread-thin stems and diminutive leaves, like sprigs of thyme.

This natural bog is a reminder of the past, one of many scattered throughout the dunes of the National Seashore. A miraculous remnant of a time before this land was denuded of trees and lush growth. Here, and in pockets elsewhere throughout the Province Lands, the ground water is close.

I wonder if the Pilgrims, just landed, found this place. I try to be close to the ghosts of their ambitions and fears, to see this still alien world through their eyes. Did the Wampanoag people forage here? I feel like they knew the bounty to be had: palm-sized clams on the sand flats, rugosa rose hips, the frosted orbs of bayberry.

Bend down. Look closer. Brush your hand over the evergreen and reveal a fairy world, scarlet spheres suspended above the peat. They hide, and they tease, these tart red rounds. They shrink from being picked. Not like raspberries or blueberries, growing at eye level, filling buckets, staining fingers, stuffing bellies. They are everywhere. Then nowhere. They trick the eye. And then one finds a cluster.

A cranberry is at its very best when it pops, a hollow crunch! when bitten. I test the harvest, popping and puckering, assured that the recent storms, alternating drought and deluge, haven’t pushed these past peak. I hone my picking technique, mimicking the wooden, hand-held cranberry rakes I see in antique shops. I use my hand like a toothed cup, gently combing the vines from the bottom up, an ovoid ruby or two dropping into my palm with each pass. I stroke the Earth. She responds in kind.

With each found berry, I count a blessing. A numbered gratitude. For my health. My ability to see, smell, touch, hear, taste. To live in this landscape, in this moment. For my family, my friends, my job, my home. For the bounty of joys and frustrations.

An hour passes. My back aches; my thighs tighten. I switch to gathering bayberries for a little while, standing more upright. But my eye is drawn back to the ground, and I am beckoned further down and into the dunes by the bittersweet lure.

And then I see it, feel it, hear the squish beneath my feet. The water. Here, in the hollow, surrounded by sand, there is standing water. A bog. I can go no further. The cranberries here seem happiest, reddest, ripest. They are less hidden, yet less accessible. Where the water has risen most visibly to the surface, the morning sky is reflected.

Eventually, reluctantly, I retrace my steps and depart this hushed hollow. Home is 300 miles to the west. With the basket of berries on the car seat beside me, I meditate: Can I preserve these beauties? If I string them for the Christmas tree, will they keep? They seem too precious to boil or bake. But I will eat them. One a day. For as long as they will keep, until they are gone. Consuming the Cape, carrying it inside me, fortified by it during the winter months when I can’t be here.

Tara Chhabra lives in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. and Eastham. She is an aspiring writer and washashore.