This is my favorite time of the year for astronomy. The air is clearer than in summer, and the nights aren’t nearly as cold as in winter, which, frustratingly, is when the sky is clearest. The planets Jupiter and Saturn, two of my favorite astronomical objects, reign supreme in the sky.

In late August, I set up my telescope at First Encounter Beach in Eastham to have a look at Jupiter with family and others who stopped by. I thought it would be a good idea to explain more about what we were seeing.

Jupiter’s name comes to us from the Romans. They believed it to be sacred to Jupiter, king of the gods, whom the ancient Greeks called Zeus. It is the third brightest object in the night sky, after the Moon and the planet Venus (another name inherited from the Romans).

King of the gods, king of the planets; Jupiter is aptly named. It is the largest planet in our solar system: 86,880 miles in diameter, more than 11 times the diameter of Earth; 1,300 Earths could fit inside it. In fact, all of the other planets of our solar system could fit inside Jupiter, with room to spare.

Jupiter has a solid core of rock and ice but is mostly atmosphere. That atmosphere is nothing like ours. It is a super dense, hot mass of hydrogen and a little helium 3,000 miles deep (our own atmosphere is about 300 miles deep). In 1995, NASA sent a robotic spacecraft into Jupiter’s atmosphere on a one-way trip to study beneath the top clouds; it made it to a depth of 93 miles — about 3 percent of the way down — before succumbing to crushing pressure and high temperatures.

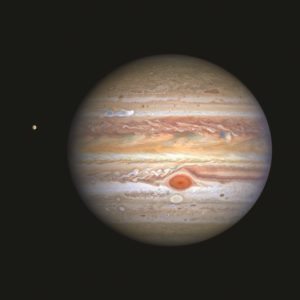

Jupiter’s colorful top cloud layer, visible to us here on Earth, is about 30 miles deep. It consists of ammonia ice crystals, which mix with upwelling phosphorus and sulfur to form other compounds. Ferocious winds tear through the clouds at more than 200 mph. These winds and Jupiter’s rotation cause the components of this top layer to form the dark cloud bands and swirls you can see in NASA photographs and amateur telescopes. Most famous of these is the Great Red Spot, a swirling hurricane larger than Earth that has been raging for at least 300 years.

The king of the planets has an impressive retinue. Eighty moons orbit Jupiter. Most of these are small asteroids or possibly comets that wandered too close and were captured by Jupiter’s powerful gravity. Some are large and can almost be considered planets themselves. The four largest are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, also called the Galilean moons for their discoverer. They are important to the history of astronomy and scientific thought in general.

In 1610, after making improvements to the optical system of his telescope, Galileo began studying Jupiter. He observed four tiny stars closely surrounding Jupiter, which you can also see in any telescope, and with binoculars if you have a steady hand. As Galileo did, you can watch these stars change position over the hours — they disappear behind Jupiter, then reappear on the other side in orderly and predictable cycles. That is, they orbit Jupiter, not Earth. For Galileo, this was proof that an Earth-centered universe, the prevailing concept of the universe for centuries, was incorrect. Enter the Scientific Revolution — and some trouble with the Catholic church for Galileo.

Jupiter is easy to find right now. Step outside after dark and look southeast. You’ll see a bright gold-white star shining about a quarter of the way up the sky; that’s Jupiter. Its brightness and rich color contrast markedly with the surrounding stars. It’s easy to imagine why the Romans, Greeks, Babylonians, and other ancient cultures all named this “star” for the most powerful gods of their pantheons.

Do you see another “star” to the right of and slightly higher than Jupiter? It’s dimmer, but its orange-gold color is clear. That’s Saturn. More about that planet next month. Until then, clear skies!