PROVINCETOWN — Kristine Weagle has been coming to Race Point with her family every summer for more than 60 years. They air down the tires on their camper and drive out on the sand for a month or more of nature, solitude, and views straight out to sea. This year, though, she spent most of her vacation parked in the Race Point Visitor Center lot, alongside a few other campers, waiting for word on the opening of the National Seashore’s prescribed route for off-road vehicles (ORVs).

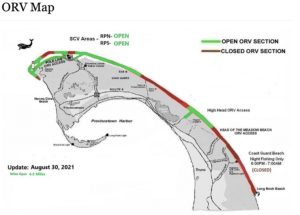

Early summer storms caused a setback for nesting piping plovers. So, the 10.5 miles of ORV passages in Provincetown and Truro that usually begin opening by early August were completely closed until Aug. 23. That day, two miles of beach were opened by the National Park Service. By Aug. 30, 4.5 miles were open. This is the first time that so much of the beach has been closed until so late in the season.

According to the National Seashore’s off-road vehicle report, one to three miles of beach in Provincetown and Truro are normally open to ORVs by August. But this season started with unseasonably cool, wet weather and two major storms over the Memorial Day and July 4 weekends washed away many of the plover nests before the young birds could fledge.

The adult plovers then started nesting again, causing an unusually late crop of fledglings on the species’ favorite breeding grounds. It is the number of surviving chicks per nesting pair that determines how well the plovers are doing, explained Mark Faherty, science coordinator at Audubon’s Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary, so it is too early to tell how this unusual year has gone.

“We all want the birds to survive, but we haven’t been on the beach this year,” Weagle said on August 22. A member of the Mass. Beach Buggy Association, she lives in Charlton. “A lot of people have given up on using the beach.”

If the term “beach buggy” sounds old-fashioned, that’s because it came into use just after World War II, when fishermen in pursuit of open surf and striped bass first began driving old bread trucks converted into ORVs through the dunes and along the shore. In 1950, a group of Cape Codders established the association to set up rules and protect vehicle access to the beaches, according to its website. While ORVs have evolved, for traditionalists the name has stuck.

The Beach Buggy Association does have a seat at the table when it comes to setting rules for human-plover co-existence. The group worked with federal and state officials to shape a recently revised policy at Nauset Beach in Orleans, for example.

Weagle is sympathetic to the birds’ plight, but not all beach buggy fans are. People on the Outer Cape are familiar with the bumper sticker on some ORVs: “Piping plover tastes like chicken.”

Last summer, Ryan Bailey, who, according to the Cape Cod Times, lives in Western Mass. but vacations in Wellfleet, started a petition “for anyone who is tired of the Cape Cod National Seashore ORV being closed due to the nesting shorebirds or other circumstances.”

Bailey’s petition argued that ORV closures were getting longer and asked that the Park open up ORV access. It also displayed mistrust of the thinking behind the Park’s rules. “For some reason the NPS doesn’t want us out there anymore and they’re using the birds as an excuse,” the petition said. It gained 621 signatures and was mailed to Seashore officials.

Seashore Supt. Brian Carlstrom said that the late opening of the beach this summer was necessary to give young birds a chance to survive. Plover eggs hatch about 25 days after being laid, and plover chicks fledge about 30 days after hatching.

The piping plover, Charadrius melodus, was federally listed as threatened and endangered in 1986. (The Northern Great Plains and Atlantic Coast populations are threatened, and the Great Lakes population is endangered.) The birds are considered threatened throughout their wintering range, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The first oversand vehicle regulations went into effect shortly after the original listing of the plover as endangered. Use of the beach by ORVs endangers the birds because they nest in and near ORV corridors. Many parts of the outer beach from Hatches Harbor in Provincetown to High Head in North Truro have been roped off every year since.

These measures are working. The local plover population has been increasing slowly but surely in recent years. In 2016, there were 66 nesting pairs and 124 fledged plover chicks counted here, according to the National Seashore off-road activity report. In 2020, there were 92 nesting pairs and 171 fledged chicks. Almost half of the nesting pairs on the Eastern Seaboard are in Massachusetts, according to Mass. Fish and Wildlife.

“But there’s no point where they get de-listed,” Faherty said. “That’s just not going to happen. People and vehicles have to be managed. And it’s not always easy because people don’t like to be managed.”

Some opponents of the beach closures point to erosion, foxes, and crows as the major threats to plovers. Those threats do become more visible, Faherty said, as the vehicle closures improve the numbers.

“But no matter how you look at it,” he said, “the reason these birds are threatened is people.” He lists the loss of beaches to ripraps (rock walls) built on the bay side and changes in the ecosystem that have paved the way for coyotes, red foxes, and crows — “these animals love suburbia” — as human-made factors behind those threats.

Carlstrom endorsed a new flexible management plan for the plover in February 2019. It will finally take effect in 2022 and is expected to increase protection earlier in the nesting season and result in fewer restrictions for oversand vehicles later in the summer.

“I want everyone to work together,” said Carlstrom. “Each year is so different. It is a real challenge. I understand the frustration.”