PROVINCETOWN — The entire nation got a new universal indoor masking advisory last week, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention put Provincetown squarely in the middle of their rationale.

The CDC reversed its May 13 advice that vaccinated people did not need to wear masks, writing in bold red text that “given higher transmissibility and current vaccine coverage, universal masking is essential.”

There is no difference in the observed viral load of vaccinated and unvaccinated people infected with the Delta variant of COVID, according to a CDC presentation leaked to the media last week. While viral load in the nose is not a direct measure of transmissibility, it’s close enough that the CDC decided the risk of transmission through the vaccinated population and back to the unvaccinated was too great.

The data underlying that conclusion were released two days later, in the form of a CDC report focused entirely on the Provincetown Covid cluster.

Over the weekend, reporters from around the world descended on Provincetown to find out what had happened here. It felt as if the pandemic were starting anew — but with Provincetown at the center of the story.

The answers to the question “Why here?” are elusive, but anomalies and unexplained delays in state reporting of data are clearly involved. If the Delta variant can be this explosively contagious, why isn’t the same thing happening in other busy vacation towns and major cities? Here are some possible answers.

Happening Everywhere?

One possibility is that breakthrough infections among the vaccinated are more widespread than has been reported.

Until last week, the CDC said vaccinated people without symptoms did not need a Covid test, even if they were in direct contact with an infected person. According to the New York Times, nationwide testing volume has declined steadily since April. The CDC stopped gathering data on breakthrough Covid cases in vaccinated people on May 1.

“As of May 1, 2021, the CDC transitioned from monitoring all reported breakthrough cases to focus on identifying and investigating only hospitalized or fatal cases,” says the CDC website. “The number of Covid-19 vaccine breakthrough infections reported to CDC likely are an undercount.”

Late Reporting Elsewhere?

Case reporting frequently lags by one to two weeks. This means an outbreak can be well underway before it becomes publicly known.

There are indications an outbreak is happening now on Nantucket. In the two weeks between July 19 and Aug. 2, 122 cases have been found on the island — up from zero in late June. Recent wastewater tests show very high concentrations of virus. The seven-day-average positivity rate for the island was at 15 percent last week — higher than Provincetown’s mid-July average of 13.5 percent.

State reporting, however, shows almost none of that. As of Aug. 3, the state’s “Interactive Data Dashboard” shows just 22 cases for Nantucket and a 3.7 percent positivity rate. That’s because the dashboard excludes the most recent 10 days of case discovery.

Late Reporting Here?

Similarly, Provincetown’s Covid outbreak was not visible in the public data until about 10 days after it started.

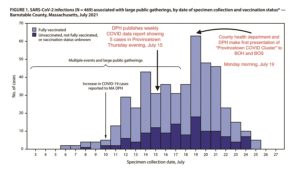

Numbers provided to the Independent by Outer Cape Health Services (OCHS) show that the rapid testing program there discovered one Covid case on July 6, one on July 7, and two on July 8. On July 9 and 10, however, there were seven cases each day. According to the CDC report on the Provincetown cluster, the state Dept. of Public Health was alerted on July 10.

OCHS recorded one new positive case via rapid testing on July 11 (a Sunday), 9 cases on the 12th, 14 cases on the 13th, and 9 more on the 14th.

The state deployed a van with PCR tests to Provincetown on July 14. It performed 251 tests that day, finding 28 more positive cases.

On the evening of July 15, however, the state published its weekly report, showing only 5 confirmed cases in Provincetown. By the previous evening, OCHS had already found 51 cases, including 28 Provincetown residents, with rapid tests. But due to the state’s delayed reporting window, and the fact that the state reports only “confirmed” PCR test results, and not “probable” rapid test results, most of what OCHS had found was not in the state’s data.

The CDC report on the Provincetown cluster notes that the state DPH issued an “Epidemic Information Exchange” on July 15 to the health departments of the other states. In other words, the DPH was alerting other health departments and the CDC of an outbreak on the same day that it published a report showing only 5 cases here.

The Provincetown cluster wasn’t actually revealed to the public until the morning of July 19, at a joint meeting of the select board and board of health. At that meeting, county health officials Sean O’Brien and Vaira Harik described the state data summary. Their presentation said that, as of Friday evening, July 16, there were 38 Provincetown residents, 51 other Massachusetts residents, and 43 out-of-state residents associated with the 132-person cluster.

According to the CDC report, however, as of Friday the 16th, specimens had been collected from 192 Massachusetts residents eventually associated with the cluster, more than twice the number reported to the public.

A team of contact tracers, including four Barnstable County public health nurses, did a huge amount of work to assemble the cluster data. OCHS communications director Gerry Desautels noted that, just because a test was conducted in Provincetown, it cannot automatically be assumed that that person is a part of the Provincetown cluster.

Data Are a Lagging Indicator

All of this simply shows that the public data lags incoming positive test results — sometimes significantly. The DPH was alerted to rising cases on July 10, but did not make a public presentation until July 19. Meanwhile, the first Provincetown resident to post his diagnosis to Facebook did so on July 9.

In fact, by some measures the outbreak here actually crested on July 19. Positivity at the mobile testing site at Veterans Memorial Community Center peaked at 15 percent on July 15. The largest number of samples that were eventually connected to the cluster were taken on July 19. Positivity held steady around 10 percent through the week of the 19th, before declining to about 6 percent the week after.

As a technical matter, the cluster is now nearly closed. According to Town Manager Alex Morse, “per the guidance of the DPH, July 31 was the last day that someone can have symptom onset or a positive test [and be added] to the overall cluster number.”

This is, of course, a wonderful development. The positivity rate on Aug. 1 was down to 4 percent. More than 1,000 people in the cluster have gotten Covid — with almost every sequenced sample being the Delta variant — and, so far, no one has died. Less than one percent needed to be hospitalized. From a health point of view, Provincetown may have gotten lucky.

There was no luck, though, in being the world’s case study. Provincetown spent at least three weeks on what is sometimes called the “bleeding edge,” learning painful and unexpected lessons that the rest of the world is now absorbing.