Over the winter, we’ve considered the Moon’s cataclysmic origins four billion years ago, its phases and visible surface features, and how it creates ocean tides. With a partial solar eclipse coming up on June 10, there’s a good reason to look at the Moon one more time.

The Moon casts a shadow. An eclipse occurs when that shadow falls on Earth’s surface. As the Moon orbits Earth, it passes between us and the Sun once every 28 days — that’s when we see the new Moon. So you might guess that an eclipse would occur somewhere on Earth at every new Moon.

But they don’t. That’s because the plane of the Moon’s orbit is not aligned with the plane of our orbit around the Sun — it is slightly tilted, by 5 degrees. This small offset is enough that the Moon’s shadow usually misses us as it crosses in front of the Sun.

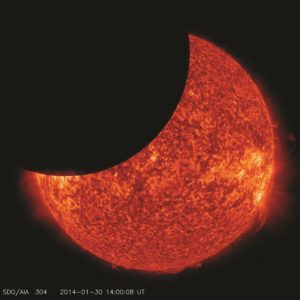

About once every 18 months or so, the Sun, Moon, and Earth come into just the right alignment at just the right time, and a solar eclipse occurs. There are three types of solar eclipses: partial, annular, and total. What you see depends on how near or far the Moon is from Earth and the observer’s distance from where the shadow falls.

An annular eclipse happens when the Moon is a little further from Earth than average. Because of that, it appears a little smaller than the Sun in our sky, so when it passes in front of the Sun, it doesn’t totally block its light — you see a blazing ring of fire around the edges of the darkened Moon.

When the Moon is closer, it completely covers the Sun for a brief time: total eclipse. The Sun is obscured by the Moon and a halo of ghostly filaments appears. That’s the corona, the plasma (ionized gas) that surrounds the Sun and is normally invisible, outshined by the photosphere, the roiling white-hot surface of the Sun.

In either case, only observers directly under the Moon’s shadow will witness the eclipse. The shadow is narrow, just 60 to 90 miles wide, and it moves fast — over 1,000 miles per hour. Eclipse chasers who go to high ground to observe it say it’s exhilarating to watch the shadow race towards them across open terrain.

For a much larger distance on either side of the shadow’s track, observers can see a partial eclipse. This is when the Moon blocks only part of the Sun, and this is what we’ll see on the Outer Cape on June 10.

Set your alarm early. The eclipse begins before sunrise. You’ll want to be at your observing location when the Sun comes up at 5:04 a.m. Anywhere with a clear view of the eastern horizon will work well. An ocean beach would be perfect.

Do not look directly at the Sun with unprotected eyes. You risk permanent damage to your vision, even during an eclipse. Sunglasses are not adequate protection. Online, NASA describes safe ways to view an eclipse.

If you’re not able to obtain safe viewing equipment in time for the eclipse, there’s another way to take in its otherworldliness. As the Moon blocks more and more of the Sun, its light takes on a magical quality. It seems as if things develop a blue-ish tint. The air cools. The intensity of sunlight weakens. Everything feels “off” somehow, but also wonderful in the literal sense of the word.

If there are trees or leafy bushes nearby, look for the shadows of the leaves on the ground. You’ll see many bizarre crescent-shaped shadows, a result of the pinhole camera effect.

At 5:32 a.m. the partial eclipse will reach its maximum extent. On the Outer Cape, the Moon will cover about 71 percent of the Sun. Then the process reverses; last contact and the end of the eclipse will be at 6:31 a.m.

If you’re unhappy with the thought of seeing only a partial eclipse, then pack your bags. The path of the full annular eclipse begins in Ontario, crosses northern Canada and the North Pole, then ends in Siberia. Road trip, anyone?