Price of Turnips Skyrockets

EASTHAM — The celebrated Eastham turnip has always been a lucrative crop. Weighing about eight pounds each — the same as a golden retriever puppy — the root vegetables are famously easier to housetrain, if somewhat harder to love.

But in the last five days, turnip prices have risen from $4 to upwards of $200 a pound. No one is exactly sure how the boom started. One theory is that people with disposable income, confined to their homes by the virus, are looking for new ways to spend money.

The recent government stimulus checks may have added to the frenzy.

Whatever the cause, Eastham turnips are flying off supermarket shelves as buyers race to hoard the last remnants of the fall crop.

“We’ve started calling turnips ‘this year’s toilet paper,’ ” said Marina Silva, a manager at the Provincetown Stop & Shop.

The price of one Eastham turnip is forecast to reach $102,033 by May 1, the same as a summer rental in Provincetown.

Outer Cape farmers see an opportunity. “Yesterday, I dug up all my lettuces and planted turnips in their place,” said Peter Staaterman of Longnook Meadows Farm in Truro on Tuesday. “My wife thinks I’m crazy,” he added. Staaterman has installed a state-of-the-art security system. “Turnip thieves are rampant right now,” he said.

Also rampant are counterfeit turnips. “A rule of thumb is: if a deal sounds too good to be true, it probably is,” warned Adelaide Smith of the Eastham Senior Center. “A good way to tell if a turnip is a genuine Eastham is to knock on it. If you hear an echo, it’s fake.”

Some people are investing in turnip futures, also known as seeds, which are going for $400 to $500 each. Meanwhile, tech-savvy buyers are using bitcoin to amass collections of digital turnips — also called NFTs (nonfungible turnips).

“We welcome this boost to the local economy,” said Jim Russo of the Eastham Chamber of Commerce. “But we should be wary — this could be a bubble.”

For now, people here are enjoying what experts at the Economic Policy Institute are calling “turnipmania.”

“This is the happiest day of my life,” said Margaret Maplethorpe, formerly of Wellfleet, after her winning bid at an auction of the Eastham Turnip Farmers’ Guild. “I’m so glad I decided to sell the house for this.” Tears of joy were streaming down her face. —Saskia Maxwell Keller

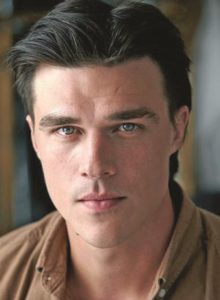

Finn Wittrock Spills Secrets of Horror

PROVINCETOWN — Finn Wittrock, one of the stars of the FX series American Horror Story, which was shooting around town in early March, squirmed uncomfortably as he sat on a bench in front of town hall.

The fresh-faced actor, who appears much younger than his official age of 36, said that, even though he was allegedly born in Lenox and studied at Juilliard, he’s actually 10,000 years old.

“I grew up in Bedrock,” he said, his eyes darting. “You know, the prehistoric town in the Flintstones. As a kid, I hung out with Pebbles Flintstone and Bamm-Bamm Rubble. My dad worked in the gravel pit with Fred and Barney. And then.…” Wittrock paused, staring up warily at the cloudy gray winter sky. “And then, I was seduced by a vampire.”

Wittrock is best known for his roles in various productions of American Horror Story creator Ryan Murphy. His characters are often queer — Rudolph Valentino in AHS: Hotel, an ill-fated hookup of Andrew Cunanan’s in The Assassination of Gianni Versace, Taylor Kitsch’s dying-of-AIDS lover in The Normal Heart — but that did not deter the young women who came to ogle at the Provincetown locations where he was filming last month.

After his experience shooting in this historic spot, Wittrock was intent on setting the record straight with the Independent: he is way older than the town. His pale skin is not just movie-star glamorous but hemoglobin-deprived; and he’s tired of pretending he’s anything but immortal.

Most of all, he wanted us to know that the storylines of American Horror Story are not just fantasy. “There’s a reason I’m cast so often,” Wittrock said. “I’m a glove fit. And I’m not the only one. You know that strange look in Sarah Paulson’s eyes? Well,” and once again, he paused. “I’ll leave that for her to say.”

The interview over, Wittrock put on sunglasses and was gone in a flash. In less than a beat, the sun peeked out of the clouds, and Commercial Street blanched in the bright light. —Howard Karren

Barry Clifford Finds Pirate’s Lost Eye Patch

WELLFLEET — The man credited with discovering the wreck of an 18th-century pirate ship here in 1984 is still pulling rich material from the deep.

Barry Clifford, who found the sunken Whydah and now runs the Whydah Pirate Museum in West Yarmouth at the former ZooQuarium, says he has recovered the eye patch believed to have been worn by Capt. “Black Sam” Bellamy.

The Whydah went down in 1717. According to other ships’ logs of that era, Bellamy may have had an eye patch, or, at least, he wore one to look tough. It’s reputed that his lover, Goody Hallett, had a thing for them, according to D.U.B. Lievedischit, Clifford’s resident maritime historian.

The fragment of black material found in the encrusted ruins of the ship has traces of what fabric historians say could be the earliest example of Velcro. A tattered pirate catalog found nearby indicated that the eye patch could be purchased as a single item or as part of a package that included a peg leg and a parrot. —K.C. Myers

Free the Oysters

Dr. Shelly Silva has a very firm handshake. She also has the letters “B” and “I” tattooed in blurry blue ink on the middle fingers of her right hand: “BI.” I glance down at them and wonder where our conversation might go. Too much information? But when she rests both hands on the edge of the bubbling open-topped tank at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, I get the full picture: “BI-VALVE.”

“I was raised in New Bedford,” Dr. Silva tells me as she swipes her hand through the water in the tank. “My father — they called him ‘High-Line’ — captained scallopers for close to 40 years. I started fishing with him in the summers when I was 16, and when I finished high school I went at it full-time.”

“I was raised in New Bedford,” Dr. Silva tells me as she swipes her hand through the water in the tank. “My father — they called him ‘High-Line’ — captained scallopers for close to 40 years. I started fishing with him in the summers when I was 16, and when I finished high school I went at it full-time.”

She tells me she scored high on the SATs. “My guidance counselors were pushing me toward the Ivy Leagues, but my soul was out there on the ocean,” she says. “Until it wasn’t.”

As she shows me through the labs, all gurgling and smelling like seaweed and low tide, the doctor openly reveals her past struggles with drugs and alcohol, ubiquitous on the docks, and how she managed to enter recovery, Harvard, M.I.T., and then the University of Hawaii for her post-doctoral work.

When we get to the largest lab, Dr. Silva brightens. The cavernous room is a combination of Fulton Fish Market and Longwood Medical Area. The bubbling sounds are still there, now accompanied by the beeping and flashing of small monitors. Wires snake out of the multiple tanks, then are gathered by zip ties into wild Rasta-like braids before entering Dr. Silva’s office at one end of the lab. I see oysters, scallops, and quahogs, some sparsely corralled and freely floating, while others are stuffed in black plastic mesh bags. The shellfish, regardless of their condition of capture here in Woods Hole, are all wired, as if this were a mass EKG event. It is spectacular to see, if not a bit unnerving.

“We received a large grant from PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) to study the effects of caging these shellfish,” Dr. Silva tells me as she gently scoops up a four-inch free-floating oyster and untangles a wire before placing it back in the tank. “A PETA board member summers in Wellfleet, I believe on Lieutenant Island, and was disturbed to see the proliferation of caged oysters.” And that, she tells me, is how it came to be that WHOI is now researching the effects that caging these creatures has on their well-being, both emotionally and physically.

I’ll admit I was at first bewildered by this news. But Dr. Silva takes me into her office — a sparse, clinical space — where she shows me a series of graphs and charts, all glowing brightly on her computers. The preliminary data clearly show evidence that caging has some negative effects with regard to beta waves, calcium formation, and movement.

“We are in the very early stages here,” she tells me, “and I try not to let my personal feelings enter into it. That would be the biggest mistake a scientist could make. I hate to see these little guys caged like this, but that’s not science. This is.”

She is now making an expansive gesture with both of her hands toward the vast room on the other side of the window. I see the word “BI-VALVE” reflected in the window separating the two rooms. —Dennis Cunningham