WELLFLEET — A large number of children who visit the Outer Cape Health Services clinic here are “under-vaccinated” — having not received a full series of standard immunizations against infectious diseases, which are required under state law for school admission.

Only 77 percent of the kindergartners at the Wellfleet Elementary School in the past three years have been fully immunized against hepatitis B, MMR (measles, mumps, rubella), DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis), polio, and varicella (chickenpox), according to the Mass. Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Sciences. This puts Wellfleet Elementary in the 10th percentile for immunizations statewide.

At Eastham Elementary, the immunization rate is only slightly higher, with 83 percent of kindergartners having received a full series of vaccines.

Increasing rates of under-vaccination on the Outer Cape mirror national and statewide trends: decreasing rates of vaccination and increasing severity of infectious disease outbreaks. Both Wellfleet’s and Eastham’s rates are well below the levels considered necessary to prevent a measles epidemic, for example.

Parents may request exemptions from the immunization requirements for medical or religious reasons. In Barnstable County, 3.4 percent of kindergartners were granted exemptions. The state average is 1.4 percent. (Dukes County, which comprises the six towns on Martha’s Vineyard, has the highest rate of exemptions in the state: 8.4 percent.)

Although kindergartners at the Truro Central School have higher rates of vaccination across the board than Wellfleet or Eastham, Truro still falls in the 10th percentile for immunization in Massachusetts, with 2.6 percent of students unimmunized. No data were available for Provincetown because fewer than 30 kindergartners attended Provincetown Schools from 2016 to 2018.

A Threat to ‘Herd Immunity’

Outer Cape Health Services (OCHS) has launched a research project to understand the reasons why increasing numbers of parents here reject vaccines. Scott Weissman of Brewster, a family nurse practitioner at OCHS who holds a doctorate in nursing practice, is heading the effort.

Weissman is worried. He explained that vaccines prevent disease by increasing “herd immunity” — the more people who are immunized, the less likely disease will spread. With fewer children being vaccinated, the risk of a widespread disease outbreak goes up.

Herd immunity stops working below certain thresholds. For example, measles can be transmitted if under 95 percent of the population is vaccinated against MMR. Eastham and Wellfleet elementary schools are both below this threshold, with only 83 percent of Wellfleet and 88 percent of Eastham kindergarten students fully vaccinated against MMR. This leaves children highly vulnerable to infection if an outbreak were to occur, as the virus would spread quickly through the population.

The University of Pittsburgh has developed a measles outbreak simulator that illustrates how high vaccination rates can limit the spread of infection. The simulation shows the daily increase in the number of active measles cases projected over a six-month span. The difference between 80-percent and 95-percent immunization rates is dramatic.

National trends confirm Weissman’s concern. Measles was officially declared eliminated in the U.S. in 2000 and, although a handful of imported cases were reported every year, outbreaks were small in the early 2000s. But they have been increasingly severe in recent years, with 971 cases already confirmed in 2019.

Measles can lead to long-term health problems. The New York Times reported on Oct. 31 on a Harvard Medical School study that found contracting measles can impair your immune system. “Measles wiped out 11 percent to 73 percent of a child’s antibodies against an array of viruses and bacteria,” the Times reported.

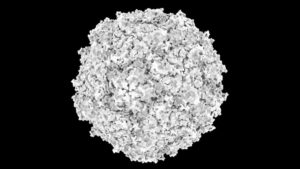

Vaccinations guard children’s underdeveloped immune systems against disease by exposing them to a small quantity of a pathogen. The body then builds up antibodies, which fight the pathogen if subsequently exposed, keeping kids healthy and preventing the spread of potentially deadly diseases. Globally, vaccines are estimated to save 2 to 3 million lives each year.

Looking for Answers

OCHS hopes to gain insight into the low rates of vaccination in Wellfleet.

In September the Wellfleet health clinic received a grant to investigate the social determinants of vaccination rates — that is, factors other than personal beliefs, such as poverty and education. The grant comes from a program funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration that targets community health centers in the state’s “medically underserved communities.”

Through the initiative the Wellfleet clinic will receive coaching and $20,000 for stipends to support the research effort.

Scott Weissman said the project will focus on families with young children who use the Wellfleet clinic for primary care. If a family has not met the schedule for vaccinations recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “we’re reaching out with a survey to find out why,” he said.

Weissman listed several hypotheses. “At first, people think about personal beliefs — religion, or whether vaccines are healthy, or whether they work,” he said.

But other factors including transportation, lack of information, poor insurance coverage, or scheduling conflicts also affect access to vaccinations. “Social determinants of health are things that we can fix,” Weissman added.

Vaccination rates across the country have been linked to social determinants. According to the CDC, high school students in rural areas have lower rates of vaccination nationwide. Nonwhite children and high school students who live at or below the poverty line also have lower rates of vaccination than their white or wealthier counterparts.

After getting a clearer picture of the local situation, the Wellfleet clinic plans to create an outreach program to address the main obstacles to getting immunized.

The team has already identified 40 to 50 families whose young children are either not immunized or under-immunized. They plan to survey these families by phone. Most families that use the Wellfleet clinic for primary care live in Wellfleet, Eastham, and Truro, although some come from Provincetown or farther up Cape.

Medical assistants, nurses, patient service representatives, and community navigators at the Wellfleet clinic will all be involved in the project, which Weissman described as “interdisciplinary.”

The clinic has also partnered with several local parents of young children who visit the Wellfleet clinic for primary care. These patient partners, it is hoped, will help the clinic with outreach by providing context and making the survey “more user-friendly,” Weissman said. “We don’t want to scare or offend people with it.”

Results of the study should be available by early spring. When asked to speculate about possible findings, Weissman said he thinks under-immunization results from a combination of personal beliefs and social determinants.

“I suspect it’s not going to be one specific thing but a multitude of different things,” he said. Although personal beliefs may factor into families’ decision-making, “social determinants are often overlooked.”

More Religious Exemptions

Statewide, the percentage of students with religious exemptions from immunization has risen dramatically in recent years. In 1990, only about 0.4 percent of students in kindergarten were granted exemptions, most for medical reasons. Today, about 1.3 percent of kindergarteners are exempted, most for religious reasons.

The Independent spoke with one parent whose children attend Outer Cape schools. He has not vaccinated his children and believes that vaccinations cause disease, quoting Biblical passages to justify this belief.

Weissman said that OCHS’s outreach program is not designed to challenge people’s faith.

“In terms of beliefs, we’re not looking to force the issue,” he said. “We’re just hoping to provide the sound science of vaccine safety for families to make a better-educated decision.”