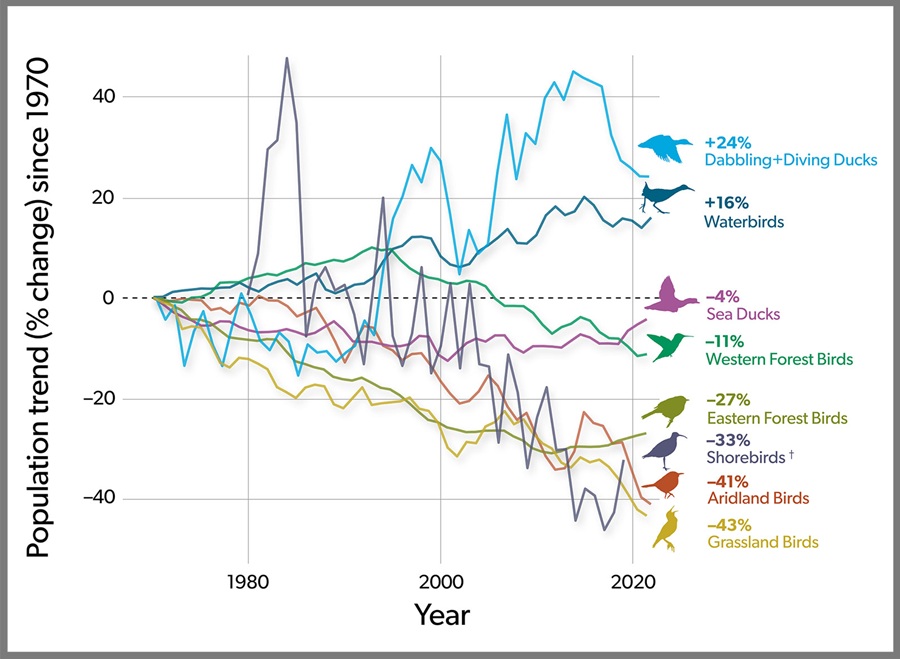

WELLFLEET — A new report on research by leading bird conservation scientists, published by Cornell University, confirms that North American bird populations are continuing a steep decline.

The North American Bird Conservation Initiative’s State of the Birds 2025 report, released on March 13, reinforces the conclusions of a 2019 study in Science that found there are 3 billion fewer North American birds than there were in 1970. The NABCI report outlines a list of “tipping point” species whose populations have declined by 50 percent since 1970 and includes shorebirds that feed on Outer Cape Cod before their long migrations and other species that nest here as among those now threatened.

While the declines are drastic, local action has the potential to help some of these species, according to report co-author Nicole Michel, director of quantitative science for the National Audubon Society. She said that conservation efforts on Cape Cod that have led to recoveries in tipping point species like the American oystercatcher and piping plover may show the way when it comes to reversing trends for other species.

Shorebirds on the Cape

Shorebirds are among the most imperiled birds in North America. Collectively, they have declined by 33 percent since 1970, with 19 shorebird species having declined at least 50 percent, according to the report.

The worst hit are long-distance migrants, which breed in the far north and migrate to the Caribbean and beyond every year. Their declines are happening so quickly that they are detectable year to year, said Shiloh Schulte, senior shorebird scientist at Manomet Conservation Sciences in Plymouth, which collaborated on the NABCI study. Included on this list is nearly every shorebird that migrates through Cape Cod, including black-bellied plovers, semipalmated sandpipers, and sanderlings.

Schulte said that these shorebirds’ long migrations present them with a range of challenges. On their breeding grounds, they contend with rising sea levels and melting permafrost. As they journey south to the Caribbean, they fly over the open ocean, where they can starve if they are unable to get sufficient food beforehand. On their wintering grounds in Latin America, they are hunted, and the shoreline habitat they rely on faces development; on their way north through the Midwest, most wetlands habitat has been converted into agricultural land. “Every step of the way, they’re getting hit with some significant challenge,” he said.

Cape Cod is the final stopover for these birds before that big flight over the ocean on their way south, said Alan Kneidel, senior conservation biologist at Manomet. His organization’s research tracking the large shorebirds known as whimbrels using satellite transmitters has revealed that it is during that open ocean crossing that whimbrels are most likely to die.

This finding, Kneidel said, suggests that ensuring these birds get enough food before their flight is among the biggest conservation priorities. This makes Cape Cod a particularly important site, as it is often the last place they feed before their flight.

Here, the biggest threats shorebirds face are lack of food and disturbance from people and dogs. A ban passed last year on horseshoe crab harvesting during egg-laying season could help, said Liana DiNunzio, a shorebird biologist at Manomet. Historically, the birds have fed on horseshoe crab eggs, but the crabs, hunted as bait and because their blood is used in medical research, are struggling, too.

Local Birds Declining Nationally

Besides shorebirds, the report names several other Outer Cape species that are in decline, with the saltmarsh sparrow at the top of the list. It’s a marsh-nesting bird and is the only Cape Cod bird on the report’s “red” list of species in truly imminent danger of extinction. Climate change is the issue: sea level rise and worsening storms are flooding their nests and shrinking their marsh habitat, which caused a 75-percent decline between 1990 and 2010, according to the American Bird Conservancy.

Saltmarsh sparrows breed on the Outer Cape in Wellfleet Harbor and Nauset Marsh, and in both places their habitat is at risk, said Mark Faherty, science coordinator at Mass Audubon’s Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary. “The marshes are just dissolving away because of crabs and sea level rise,” he said, referring to purple marsh crabs that overgraze salt marshes here.

The long-tailed duck, an Arctic waterfowl that winters in the waters around Cape Cod, is a more commonly seen bird that has experienced more than a 50-percent decline. The reasons are mysterious, said Michael Brasher, senior waterfowl scientist at Ducks Unlimited and co-chair of the committee that wrote State of the Birds 2025, but two likely reasons are climate change damage to their Arctic breeding grounds and disturbance from fishing and industrial development and pollution to their wintering grounds on the Atlantic coast. “It’s death by a thousand cuts,” he said.

Another tipping point species is the eastern towhee, a black-and-orange sparrow that is abundant on Cape Cod. This species is found in shrubland, a habitat that has declined in part because of development, but also because it is succeeding into forest without new shrubland to replace it, Faherty said. While there are still “boatloads” of them on the Cape, he said, they are declining; according to a trend map released by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, towhees on the Outer Cape declined by around 11 percent between 2012 and 2022.

Perhaps the most surprising common bird the researchers found to be declining is the great black-backed gull, a massive bird that is found on nearly every beach on the Outer Cape. Their abundance and brash nature can mask their decline, said Sea McKeon, Marine Program director at the American Bird Conservancy. Great black-backed gulls have declined worldwide by 50 percent in just the last 40 years, according to a study led by researchers from the University of the Highlands and Islands in Scotland. On the Outer Cape, their trend map reveals that they’ve declined by 23 percent since 2012.

McKeon said that part of this trend is because we have fewer uncapped landfills on the East Coast — which inadvertently became these birds’ feeding grounds during the early part of the 20th century. Nobody wants the return of those dump sites, “but what we’re seeing in decline is not fully lining up with just that factor,” he said. He points to plastic ingestion, a decline in fish stocks, and overuse of the beach spaces where these birds nest as possible contributors. As with so many of the report’s “tipping point” species, “we’ve got lots of different pieces of a puzzle we haven’t figured out yet,” he said.

Protecting Rest and Refueling

For both great black-backed gulls and long-tailed ducks, which both suffer from disturbance, leaving these birds alone is key to protecting them. “No one wants to be the fun police,” said McKeon, but when it comes to dogs or children chasing birds, “that’s charming to you, but terrifying and costly to those birds.”

This is especially true for migratory shorebirds, because when they stage on Cape Cod to prepare for their cross-ocean travel, every bit of rest and food they get matters. “The majority of people that I talk to don’t understand how precarious the shorebird situation is,” said Lisa Schibley, North American coordinator for the International Shorebird Survey at Manomet. “If they don’t get a rest right now, today, they may die.”

Saltmarsh sparrows, meanwhile, may benefit from saltmarsh restoration work that is going on around the Outer Cape, said Mark Faherty, where besides the project on the Herring River, work is beginning on the Pamet River and planned around Wellfleet Bay Sanctuary.

Three conservation success stories on Cape Cod offer some lessons: piping plovers, least terns, and American oystercatchers all had experienced declines of more than 50 percent — between 1970 and the 1990s for the plovers and terns and the early 2000s for the oystercatchers — but have seen massive recoveries in the state since. “Massachusetts has a really good track record in bringing back East Coast water birds,” Faherty said.

The NABCI report lists the American oystercatcher, whose population has increased from 10,000 in 2009 to 14,000 today, as the prime example of a conservation success story. That recovery is thanks to conservation groups from Massachusetts and elsewhere protecting nests from disturbance, Faherty said.

“These birds are declining across their ranges, but the way we’re going to turn things around is by acting local,” said Nicole Michel. “Collectively, people everywhere taking those small local actions can bend that bird curve to bring birds back.”