This article was updated on Oct. 10, 2024.

PROVINCETOWN — Ten bastions of North America’s crier culture came to town hall on Oct. 7, each one there to cry twice in front of four judges and several dozen spectators in hopes of winning the first in-person town crier competition in the U.S. since 2019.

From Alexandria, Va. to New Glasgow, Nova Scotia — and eight other towns and cities in between — they came at the invitation of Provincetown’s own crier, Daniel Gómez Llata, with David Rose, president of the American Guild of Town Criers, helping organize the event.

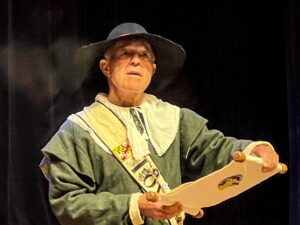

Llata is keeping up a longstanding tradition. Apart from some lapses during World War II and the 1980s, Llata said, Provincetown has had a crier since 1849. Back then, it was a municipal job that provided news to the people. Being the crier here is still a job, paid for by the town’s Chamber of Commerce. “I’m kind of an unofficial ambassador,” said Llata. “It’s important that the old world still exists in the modern world,” an idea that seemed to underpin the cries heard on Monday — all of which had to come in at under 125 words.

Each cry was evaluated on entry and exit, projection and clarity, content and structure. Penalties that whittled away would-be perfect scores were assessed by judges John Angus Spencer-Barnes, a crier from Lancaster, England; Jeffrey Huard, who was filling in for Provincetown’s crier emeritus Kenneth Lonergan; journalist and historian David Dunlap; and select board member Leslie Sandberg. Kenneth Freed, a CPA who lives in town, tabulated the scores, which weren’t revealed until later in the evening at an awards dinner at Luke’s Lobster.

The first cry, a “home cry,” extolled the virtues of the criers’ hometowns, among them cookie factories, harbor economies, and the fermentation of Worcestershire sauce. A mix of comedic timing and the patriotic enthusiasm of “God Bless America,” “Let Freedom Ring,” or for Canadian competitors, “God Save the Queen,” composed the cries’ oratory backbone.

“There once was a man from Nantucket,” began Eric Goddard of that town, reading his limerick-style cry from a scroll to rolling laughter.

“Greetings from Burlington,” declared David Vollick, wearing a feathered tri-corner hat. “The one in Ontario — not the one in Vermont!”

“Never heard of us? You are not alone,” cried Ronnie Stevans of Hampton Township, N.J., which has “not one but two fast-food establishments.”

In a second cry, a historic cry, each crier had to announce an event from Provincetown’s history. In a style that recalled the eccentricities of Edward Lear and the nonsensical rhythms of Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky,” Llata began to describe a piece of lore about the supposed appearance of a sea serpent in Provincetown Harbor in 1886.

“On the morning of August the second, a Monster appeared, so I reckon,” cried Llata. “I saw in the ocean a swirling commotion of steam jets arising offshore. Consulting my flask, a monstrous mask arose from below to the surface; I feared I be killed, or maybe char-grilled, or might it be psychoneurosis?”

He continued: “It seemed prehistoric and phantasmagoric, a smoldering, briny iguana. For those who may snicker, it wasn’t the liquor resulting in any delusion. I am the Town Crier, so not quite a liar, though that is the foregone conclusion.”

Some of the other criers followed suit in folly.

“I’ve been dispatched from Upper Canada to voice strong consternation, nay absolute indignation, at the deplorable Provincetown declaration concerning our Canada geese,” said Bruce Kruger, town crier for Bracebridge and South Bruce Peninsula in Ontario.

Kruger was referring to the Provincetown town meeting in March 1810 that had banned Canada goose from roaming the town at large.

Other criers celebrated historic figures in earnest, like the Pulitzer-winning playwright Eugene O’Neill or the sea captain Christopher Hussey, who revived whaling with his killing of the first sperm whale for the sake of the industry in 1712.

Also extolled were the 28 houses floated from Long Point to the West End, the 1899 establishment of the Cape School of Art by Charles Hawthorne, and the “feeling of freedom and acceptance” in Provincetown for the LGBTQ community. Llata told the audience that the very building they were in had, at one point, seen more legal same-sex marriages than anywhere else in the world.

Benjamin Fiore-Walker, the second African-American town crier of Alexandria, recounted the sinking of the English frigate HMS Somerset off Race Point in November 1778.

“She played a vital British role during the revolution, but for what patriots didn’t, Mother Nature did have a solution,” said Fiore-Walker. “The ground provided the needed emotional boost for the scavenged war materials the wreck produced.”

After Fiore-Walker concluded his rhyme, Llata noted that the gavel and baton at King Hiram’s Lodge, the local Masonic gathering place, were made from wood salvaged from that shipwreck.

The last cry of the day achieved a fitting poetic symmetry by ending with the beginning, or at least one version of it.

David Rose, who besides being the criers’ guild president is town crier for the Dorchester County Chamber of Commerce in Maryland, gave his interpretation of the Mayflower Compact, an agreement for a “civic body politic” made on Nov. 11, 1620 by the adult male passengers of the Mayflower.

“Let us pray to God that we have the strength of character to abide by this covenant and not worship a golden calf,” said Rose, after which the competition concluded with a collective ringing of the handbells and the cheers of the audience.

David Vollick of Burlington, Ontario placed first. Stephen Scott Findlay of Lunenberg, Nova Scotia placed second. James Stewart of New Glasgow, Nova Scotia placed third. The judges selected Tim Yuskaitis of Fair Lawn, N.J. as the “Best American Crier.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article, published in print on Oct. 10, included several errors in Daniel Gómez Llata’s historical cry about the sea serpent, which have been corrected in this version.