Candy Darling’s face could not be forgotten. It glued itself to the minds of the auteurs of late ’60s New York, her beauty playing out ad infinitum in their songs, their movies, their photographs.

She is known for Andy Warhol’s 1971 Women in Revolt, in which she starred as a socialite roped into a militant feminist cause; Lou Reed croons about her in the Velvet Underground’s 1969 “Candy Says,” where she is the eponymous creature that yearns for easier days ahead; and she was front and center in Tennessee Williams’s 1972 off-Broadway play Small Craft Warnings.

With her teased-out blond hair, her doe eyes, her eyebrows plucked thin like an Old Hollywood starlet, Darling was beautiful. In part because of that beauty, Darling was one of the most — if not the most — visible transgender women in New York City. She did not identify herself as trans; the terminology at the time was not useful to her (she was no drag queen), and we cannot know whether contemporary identifiers would have suited her any better.

Evan more than for her beauty, Darling was known for her unadulterated “aura,” as Truman Capote put it. Every photograph of her came alive. It was she, the muse, who made artworks both bright and somber. All those men wanted to capture that quality. We remember her largely on their terms — but what about hers?

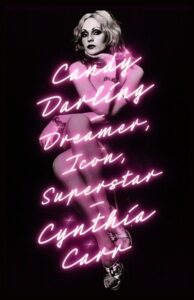

In Cynthia Carr’s new biography, Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar — published last month by Farrar, Straus and Giroux — the author moves past the mythologizing that surrounded the muse and offers a complete, strict chronology of Darling’s life. The result is a service to anyone who wishes to understand Darling, and the book is at its best when it stays close to the record, leaving interpretation of Darling’s character to the reader.

Darling comes alive through excerpts from her diaries, a vast archive that begins in 1958 when she was 14. She has a quick wit and isn’t easily ruffled. When she was 15, she went to see the school “phsychiatrist,” as she put it, who “tried to tell me I’ve got a problem and I’m queer!” A red squiggle points to an annotation in the margin, most likely from three years later, that reads, “As if I didn’t know all along.”

Before Carr’s biography, the 2010 documentary Beautiful Darling was the only available chronicle of Darling’s life. The film is Scotch-taped together and riddled with washed-up Warhol factory talking heads (Fran Lebowitz included) who are set on litigating whether Darling “passed” as a woman. They altogether fail to focus on her distinctive personality.

Though many facts of Darling’s life are reported for the first time in Carr’s book, the reader does not reach the end with a sense of “getting” Darling much more than at the outset. Darling is evasive, and much of her aura rests in mysteries and inconsistencies.

That secrecy is a central part of who she was. She said so herself: “So many times in life, one must put on an act,” Darling wrote. “As a child I learned to don the mask when the occasion called for it. (Later I learned to don the wig.)” The many lock-and-key diaries she filled in her adolescence and 20s reveal brazen dreaming but also an unabating loneliness.

Carr, who also wrote Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz, begins with Darling’s childhood in Massapequa Park, Long Island with a kindhearted if timid mother and abusive father. One day, she wore a dress in front of her mother for the first time, roughly around age 16 or 17. In that moment, her mother said she knew she “couldn’t hold my son back.”

Darling soon flew the coop. First to a local gay bar, the Hayloft, then to the Long Island Railroad to visit her friend’s antique shop on Bleecker Street. In no time, she was gliding down the streets of Lower Manhattan, stoop-sitting with the street queens and crashing at the Chelsea Hotel. In 1967, she met Warhol and became one of his superstars, but even at the peak of her fame she was often without a place to stay or assurance of when the next paycheck would come.

It is an understatement to say that Darling experienced great misery and daily violence up until the day she died. She felt constantly alone, revealing to her diaries what she rarely said aloud: “I feel like I’m living in a prison,” she wrote. “I see so much of life I cannot have.”

That she maintained and delighted in her persona and her beauty seems to Carr a bitter contrast with this ugly reality. “The world she created in her mind, the world where she was the alluring goddess and star, was a closed world,” writes Carr.

Yet Darling was a star, someone with a profound presence that burns the eye of anyone who looks at, for instance, that final photograph by Peter Hujar — the famous one, in which Darling lies in a bed in Cabrini Hospital with lymphoma, a red rose tossed across her bedspread, all drama.

Carr’s suggestion that Darling’s sense of self was a “fantasy” is the one place where the author misses the mark. In the scraps of her diaries and the stories of her life, one doesn’t get the sense that Darling strove for perfection — or even wanted to project it. Instead, her persona was her respite and her art. It may have been a form of fiction, but it was never a seamless façade. Like any good work of fiction, it was a story that anyone who reads her words, hears her voice, or sees her face flickering across the screen is immediately compelled to believe.