There is a certain protective haze that encircles our early memories. Sometimes it is hard to discern whether what we remember is accurate or if the memory has been overlaid by retellings and photographs. For Stephanie Vevers, who grew up in a family of artists, a painting can be yet another distortion of memory — but one from which she draws meaning and a line of continuity.

Vevers, 68, has worked as a researcher, technical writer, editor, videographer, and video producer. Most recently, she has been a copy editor for scholarly and journal articles, novellas, dissertations, and English translations from Finnish, Italian, and German. She doesn’t call herself an artist, but her life has been shaped by art, including a lifelong immersion in her family’s work.

Born in 1955 in New York to the artists Tony Vevers and Elspeth Halvorsen, she grew up in Provincetown, North Carolina, and Indiana. In her late teens, Vevers toured the art museums of Europe in a nine-month self-directed study. Wanting to experience new creative environments and emerging art forms, she moved to New York at age 20, influenced by a New Yorker article about theater director and visual artist Robert Wilson and his experimental performance collective called the Byrd Hoffman School of Byrds.

“I took in all the art forms being practiced in New York in the 1970s, from avant-garde and experimental film to dance, poetry, abstract music, and painting,” says Vevers.

She worked as a videographer in Austin in the 1980s and 1990s, at the height of the city’s cultivated weirdness. Now, she splits her time between Brooklyn and Provincetown, where her creative odyssey really began.

Vevers recently guided visitors at the Provincetown Arts Society’s Mary Heaton Vorse house through an exhibit that includes works by her father, her sister, Tabitha Vevers, and her brother-in-law, Daniel Ranalli, among others. (The exhibit continues through mid-January.)

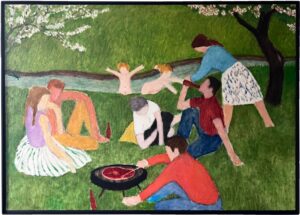

She walked to the far side of the living room and stopped in front of a large canvas, A Picnic at Herring Run, painted by her father in 1960. Compared to the two other Tony Vevers paintings on display, which depict lone figures in neutral shades, this painting is a verdant shock.

The painting maps a formative early memory. “I remember I was wearing black patent leather shoes that day,” said Vevers. “The adults were in the water, throwing herring out. The fish flopped around on the bank. For a five-year-old, those images were sensuous and vivid.”

Vevers had not spoken publicly about her parents’ artistic output before, but now, she said, she is finally ready to do that. She had been thinking about where this painting fits into her father’s production. It seemed to her as if it had been done quickly.

“Most of my father’s paintings were made in a soberly careful and deliberate sort of way,” she said. “This one seems almost like he could have gone home that night and painted it from memory.”

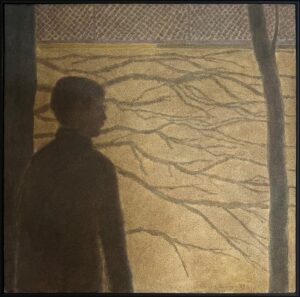

Vevers believes that Night Shadows, one of the other Tony Vevers paintings in the current exhibit, is a self-portrait done in the back yard of the family’s house on Law Street in Provincetown. The third painting, Doorway, is a portrait of her mother, which she believes may have been inspired by the doorway of their house in Indiana.

In A Picnic at Herring Run, three faceless couples picnic on the bank of the Herring River near its source in Wellfleet. The composition is circular, and Vevers identifies the figures in sets of two. There are her parents, Tony Vevers and Elspeth Halvorsen, an artist known for her sculptural assemblages and photography, and their friends, Marcia Marcus and her husband, Terry Barrell, and Bill Barrell and his wife, Irene Baker. All were artists.

“I think Marcia was pregnant then,” said Vevers, indicating the female figure reclining at the center of the canvas. “She was the main working artist in the relationship. Terry took care of their home.”

These artists’ early careers intersected with those of the Abstract Expressionists hanging out at the Cedar Bar in Greenwich Village. They made their way to Provincetown in the mid-1950s, settled into its seasonal rhythms, and built their families and practices. In a 2019 obituary for their mother in the Independent, Stephanie and Tabitha described their family’s early years in Provincetown as a time full of community and merrymaking.

After Tony Vevers started teaching studio art and art history in 1963 — first at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and later at Purdue University in Indiana — the family returned each summer to the house Mark Rothko sold them on Bradford Street. Stephanie remembers the shadow of Mary Heaton Vorse’s son, Heaton Vorse, looming in the front window of the room now featuring her family’s artwork as she and the other kids ran barefoot down Commercial Street.

In the painting, the men drink beer while her father tends to a steak on a small grill. It’s spring, and two blossoming trees bookend the gathering. Two naked children play in the stream.

“That’s Tabitha,” said Vevers, pointing to the child standing in the water. Her outstretched arms and small orange-brown head resemble a star.

Stephanie is depicted in the same pearly tones as her sister but angled away from the other figures. She reaches out toward her mother on the bank.

For Provincetown artists of that time, work and family life were not separated. It was all an act of creation. Domestic scenes inspired art, and art inspired child-rearing; children were flesh and blood as well as oil and acrylic.

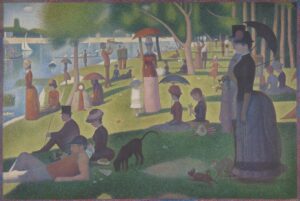

Vevers also commented on the painting’s artistic inspiration: the French undertones of its theme and its Impressionistic brushstrokes. On his phone, one visitor pulled up Édouard Manet’s The Luncheon on the Grass (Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, 1863) and then Vevers looked up Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-1886) on her phone. All three paintings call attention to how society flourishes against the backdrop of bucolic nature.

“It is intriguing to notice how the painting is of its time,” said Vevers. “It represents getting back to nature, but there’s the grill, this 1950s-era manufactured item.”

Like an umbrella or sailboat in Seurat’s painting, the grill is a technology of the present set against the natural world. The same might be said of Vevers herself, as both child and critic.

To schedule a visit to the Mary Heaton Vorse house (466 Commercial St., Provincetown) to view the current exhibit, email [email protected].