For much of Provincetown’s history, whales have been central to its economy and identity. The Wampanoag people used every part of the whale. The first entry made in Mourt’s Relation, the Pilgrims’ journal, after the Mayflower arrived in Provincetown Harbor describes how, from their ship, “every day we saw whales playing hard by us.”

It also notes the Puritans’ dismay at not having the tools to hunt the whales, get their oil, and reap the “very rich return, which to our great grief we wanted.”

From the pre-Revolutionary War days all the way to the final voyage in 1921, whaling ships left Provincetown in pursuit of precious resources: barrels of whale oil for lamps and candles and thousands of pounds of “whale-bone” (some of what was referred to as “bone” was actually the baleen of the right whale) for products like corsets and umbrellas.

While many might designate 1916, when the painter Charles Hawthorne arrived, as the year Provincetown became an art colony, at least one group of makers were carving and sketching in those early whaling days. The art was made by whalemen on their vessels — a practice known as scrimshaw as long as it was “crafted on shipboard, on whaling voyages, and from materials obtained in the fishery,” according to Michael Dyer, curator of maritime history at the New Bedford Whaling Museum and author of O’er the Wide and Tractless Sea: Original Art of the Yankee Whale Hunt.

Scrimshaw often took the form of intricate carvings, Dyer says, on sperm whale teeth and jawbones and on baleen, on exotic woods, shells of various kinds, walrus tusks, and oddball animal parts like shark vertebrae, porcupine quills, and turtle shells.

Scrimshaw is sometimes referred to as the only unique art form that began in the United States. But that’s a notion that ignores centuries of indigenous people’s art. And European whalemen were carving bones and baleen well before the Americans, according to Eric Jay Dolin, author of Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America.

Still, in ports from New Bedford to Nantucket and New London to Provincetown, Dolin writes, “It was the Americans who took scrimshaw to its greatest heights.”

Scrimshaw depicted a range of images, from ship portraits to fanciful freehand drawings of houses and landscapes. The works, Dyer says, were often given as gifts to women awaiting the sailors’ return but just as often were gifts from one sailor to another.

The artworks were often practical. Scrimshaw canes, boxes, or yardsticks were not uncommon. “Most people think scrimshaw is pictures on whale teeth,” says Hyannis Port antiquarian Alan Granby. “At least half of scrimshaw is utilitarian.” Granby was guest curator of the 2022 exhibit Scrimshaw: The Whaler’s Art at the Cahoon Museum of American Art in Cotuit.

A major challenge in the study of scrimshaw is that most pieces are unsigned and therefore impossible to tie to a specific carver, whaling ship, or port of departure.

But some pieces provide clues to their provenance. Provincetown’s scrimshaw reflects the family-owned, small-business nature of the town’s whaling expeditions. Voyages from here were shorter trips, called “plum pudding voyages,” Dyer says. “Highly skilled people, small vessels, quick voyages, get your cargo, get it to market, go out and do it again” was the Provincetown way. In 1845, for example, of the 22 whaling vessels that sailed out of Provincetown, only three were large ships; the rest were smaller brigs or schooners. All but one returned to the harbor that same year or the next. Bigger ports including New Bedford and Nantucket sent out much larger ships that were gone for three to five years at a time.

With scrimshaw being a pastime for the homeward passage, when the whaling was done, and because Provincetown ran shorter trips, the pieces made by Provincetown whalemen were generally on a smaller scale, representing work that could be finished quickly.

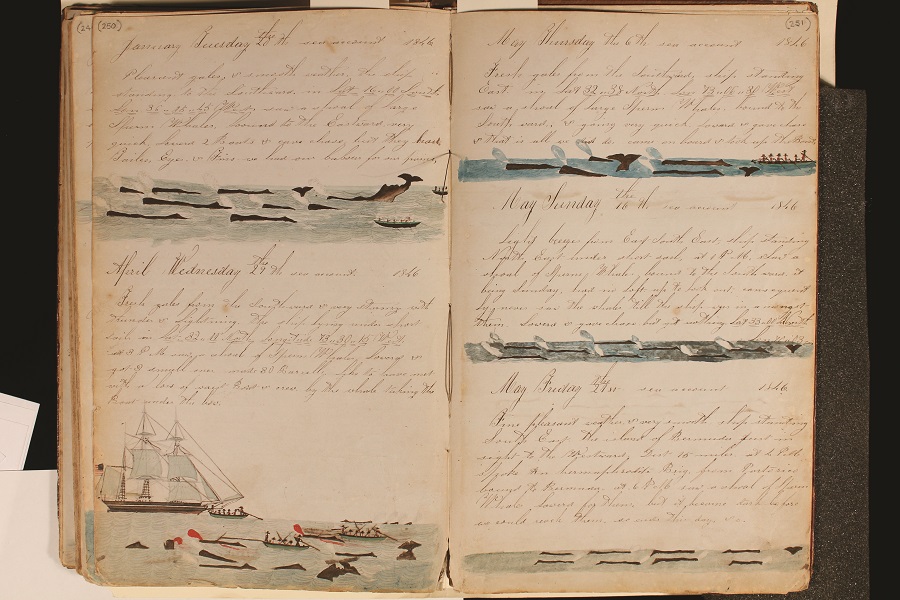

Another distinction of Provincetown’s scrimshaw history, according to Dyer, is that Provincetown whalemen documented their carvings more than others did by describing the practice in their journals. One such journal was done by Joseph Bogart Hersey, a career whaleman who in 1843, on board the schooner Esquimaux out of Provincetown, described “sawing up the large whale’s jaws” after a kill. The jaw bones, he goes on to write, “yielded several canes, fids and busks.” (Busks were stays used in corsets.)

Hersey described being “slightly skilled in the art of flowering; that is drawing and painting upon bone.” He was skilled enough that his fellow sailors implored him to make pieces for them. “I have many demands made upon my generosity, and I don’t wish to slight any,” he wrote. “I of course work for all.”

Some of the greatest illustrated whaling journals came out of Provincetown, Dyer says. “There was a real sense of art in the Provincetown maritime community,” he says. Whaling journals were filled with documentary illustrations drawn by sailors as records of where whales were seen or caught.

The art of whalemen — scrimshaw and illustrated journals — disappeared here with the demise of whaling in Provincetown, brought on primarily by the 1859 discovery of petroleum, then by the Portland Gale of 1898. That storm destroyed half of Provincetown’s wharves, according to Krahulik’s history of the town.

One of the beauties of scrimshaw is its temporality — the fact that these pieces were made only in an 80-year period by people working in a profession that is itself a remnant of the past. It is illegal to practice the craft today under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. And it is illegal to sell scrimshaw if it was not made before 1973.

Dyer says that, despite some people claiming to do modern scrimshaw, for scrimshaw to be authentic it must have been done on shipboard by a whaleman. “People just imagine that if it’s ivory or bone and it’s got engraving on it, that is scrimshaw,” he says. As for what’s marketed now as scrimshaw, he adds, “A lot of it is plastic; it’s not even real stuff.”

There are still ways to appreciate the whalemen’s art. A small number of scrimshaw pieces are on view at the Provincetown Museum, the world’s largest collection is just off-Cape at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, and there is another impressive collection at the Nantucket Whaling Museum.

Dyer says that the freedom whalemen had to carve whatever they liked means scrimshaw offers unfiltered snapshots of 19th-century culture and the lives of whalemen. It gave the men the opportunity to say, “This is what’s important to me — this is what I’m going to choose to spend the next 72 hours of my life engraving on this tooth of a whale that I helped kill,” Dyer says. “There are just so many stories.”