PROVINCETOWN — Reports in recent years from the Association to Preserve Cape Cod (APCC), which uses data collected by the Center for Coastal Studies (CCS) at more than 100 testing stations in Cape Cod Bay and Nantucket Sound, show a steady decline in coastal water quality.

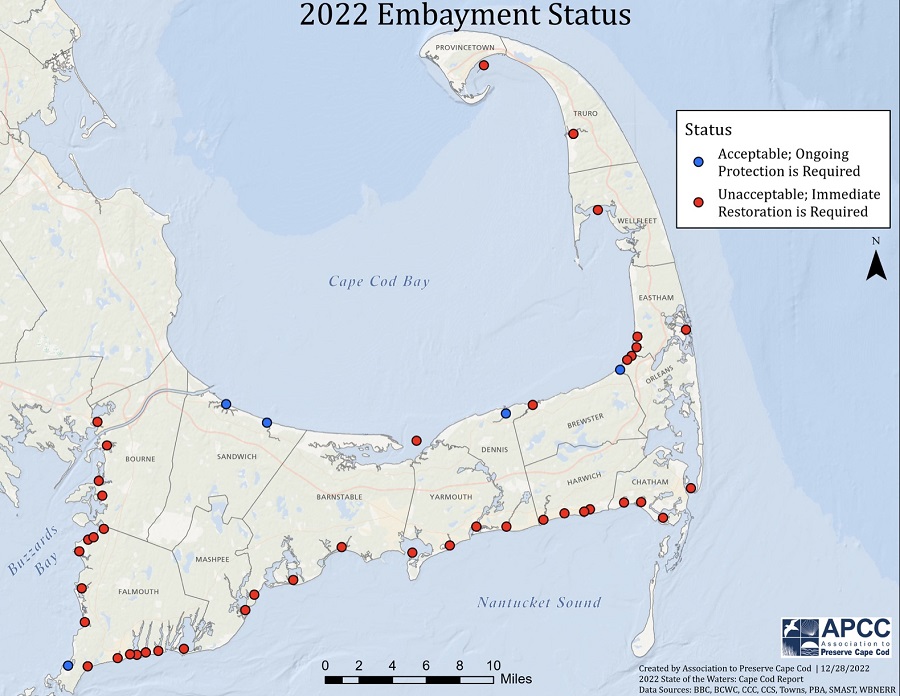

From 2019 to 2022, the proportion of coastal coves known as “embayments” deemed unacceptable in APCC’s State of the Waters report rose from 68 percent to 90 percent. And whereas Provincetown Harbor, Wellfleet Harbor, and Eastham’s Rock Harbor have shown issues before, Truro’s Pamet Harbor was deemed unacceptable for the first time in 2022.

The quality of water in coastal embayments is critical because of the shellfish, finfish, and bird populations they support — and for what it suggests about the Cape’s drinking water, according to Amy Costa, director of the CCS Water Quality Monitoring Program, which is funded primarily by a contract with Barnstable County. Poor coastal water quality can be an indicator of upland water quality problems, Costa told the Independent. “You’re going to eventually see it everywhere,” she said.

While Outer Cape residents are by now used to summer reports on algal blooms in freshwater ponds, the process affects ocean water as well. The Buzzards Bay Eutrophic Index is used across Cape Cod to track eutrophication — the process by which high levels of nutrient loading spur algae blooms, which can eventually lead to hypoxia, or low oxygen levels.

“Nitrogen is the nutrient that fuels the system,” Costa said. “If there’s too much nitrogen, there’s going to be too much phytoplankton. If there’s too much phytoplankton, that means water clarity will probably go down because it makes the waters more turbid.”

When phytoplankton blooms in excess and then dies, decomposition uses up dissolved oxygen in the water, which kills fish and other animals that need oxygen to survive. “It’s a cycle that just keeps going,” Costa said.

“Septic systems seem to be the primary source of nitrogen on the Cape,” Costa said. Title 5 septic systems are designed to filter bacteria out of human waste rather than nitrogen, although proposed regulation changes from the state Dept. of Environmental Protection (DEP) aim to reduce nitrogen loading much further, setting a total maximum daily load for 70 embayments in southern Massachusetts.

Municipal sewer systems are expensive for taxpayers — Eastham’s new system could run from $80 million to $150 million, according to Health Director Jane Crowley — but installing hundreds or thousands of high-performing home septic systems would be expensive, too.

In 2019, an extreme hypoxic event, in which bottom waters were stripped of oxygen, resulted in a wave of lobster mortality — although Costa said that event was believed to be caused by warming waters and an invasive species of phytoplankton rather than nitrogen loading.

In the wake of that incident, the state Div. of Marine Fisheries (DMF) set up an early warning system. The CCS sends water data to DMF, and if there are fewer than four milligrams of oxygen per liter in bottom waters — where lobster traps lie — DMF dispatches a hypoxia warning to fishermen so they can move their gear.

The effort to track nitrogen in Cape Cod Bay stretches back more than 20 years, to the multi-billion-dollar Boston Outfall project that redirected 350 million gallons per day of treated effluent from Boston Harbor into an outfall pipe 36 miles north of Cape Cod Bay. In 2005, after four years of monitoring, the CCS found that the design of the outfall pipe was effective, and the effluent had minimal impact on Cape Cod Bay.

The Center for Coastal Studies continued monitoring water quality after that, adding more stations in 2006 and then expanding its work into Nantucket Sound, Costa said.

With the help of citizen scientists, the four-person CCS water-quality monitoring team tests each of its stations every two weeks from May to October and once in February for a “winter snapshot.” Oxygen levels are generally higher in the winter, said Jenny Burkhardt, a research assistant on the water-quality team, because there is “less biological matter using it up.”

The Cape Cod and Islands Water Protection Fund has been offering a 25-percent subsidy to municipal wastewater projects, but its revenues will likely be overwhelmed by the volume of new projects on Cape Cod. Another approach to the nitrogen loading problem would be a permeable reactive barrier that could “trap or take up the nitrogen as water flows towards the bay or the ocean,” according to Costa.

“There’s going to be a lot of pushback because of the expense,” Costa said. “As homeowners on Cape Cod, we can’t afford it. But it has to be done.”