WELLFLEET — A clap of thunder punctuated Frank Robert Tangherlini’s recollections of decades of public service at a gathering at his son’s house here on July 25. The physicist was hardly fazed by a passing storm — he’s spent his career studying variability.

Neighbors, friends, and family members were there to listen as the World War II veteran, who is 101, described his experience to Andrew Biggio, a U.S. Marine and commander of Post 30 of the American Legion in East Boston. Biggio is compiling oral histories of World War II veterans.

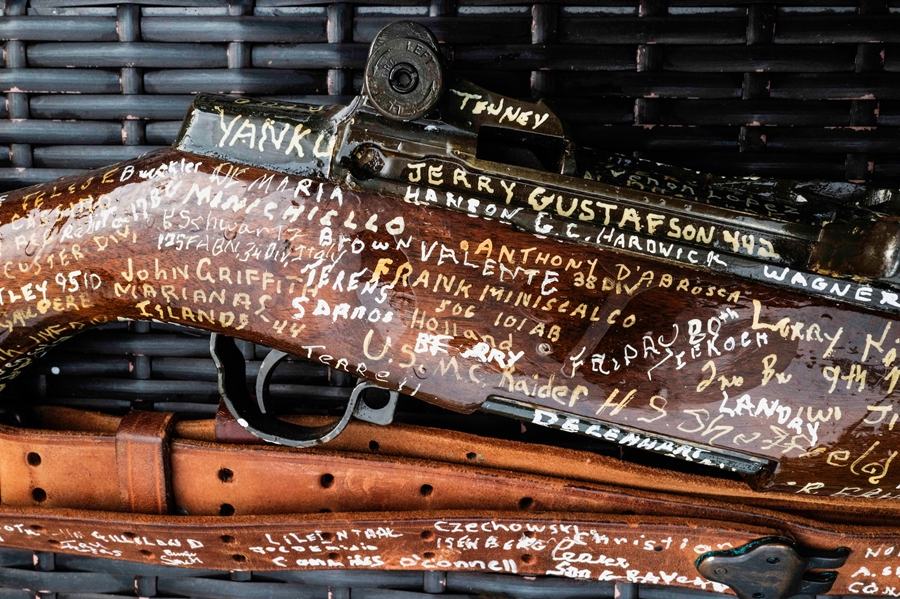

As he collects stories, Biggio is also gathering the signatures of these men who may never have met, having served in different theaters of combat, on a rifle. The gun is a ceremonial version of one they likely all handled, the Army’s standard service rifle at the time: the M1 Garand.

“I wanted to represent the whole war on the rifle,” Biggio said. Tangherlini became the 501st veteran — and likely the last, Biggio said — to sign the 1945 antique. Biggio’s idea is to give the histories and the rifle to the American Heritage Museum in Hudson or the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

‘We’d All Jump Together’

More than 80 years ago, in December 1944, Tangherlini fought in the Battle of the Bulge, a turning point for the Allied forces, in which the U.S. lost some 19,000 soldiers. He was a 506th Regiment parachute infantryman with the 101st Airborne Division and is a survivor of the harrowing two-week siege of Bastogne, defending the Belgian city against advancing German troops until Gen. George Patton’s reinforcements arrived.

His studies in electrical engineering at Boston College exempted him from the draft, but seeing friends not eligible for that deferment, “I decided I wanted to join” out of a sense of fairness, he said. He left his hometown of Boston to train in Georgia and was soon on a ship to Liverpool.

He expected to serve as a technician or pilot but soon found that the need was elsewhere. “They wanted people for the 101st to make up for losses in the Operation Market Garden, which had taken place in Holland,” he said. With two fellow cadets he’d befriended from Nebraska and Connecticut, “we decided we’d all jump together.”

After the war, Tangherlini spent his life at the frontier of theoretical and particle physics — adventures he’s as eager to recount as stories of service on the Western Front. He received a bachelor’s degree at Harvard in 1948, studied with Enrico Fermi in a master’s program at the University of Chicago, and got a Ph.D. at Stanford in 1959.

In the 1970s, Tangherlini began coming to Wellfleet with family while he was a professor at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester. He continued to cross the country for visits after his son, Daniel — prompted by childhood memories of theater, camping, and penny candy — bought a house here in 2018.

‘The Fortunes of War’

The siege of Bastogne was pivotal to the Allied advances in western Europe in late 1944. After receiving word of a surprise German offensive in the wooded Ardennes in southern Belgium, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was serving as Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces, on Dec. 16 ordered the 101st Airborne forward to Bastogne before the city was surrounded. It was an opening move in the Battle of the Bulge.

Tangherlini remembers the news coming on a Saturday, and how, by that Tuesday, he had jumped off a truck in Belgium and was trudging toward a hillside farmhouse to build slit trenches.

The soldiers were outnumbered, cold, and short-supplied. “Within a couple of days, it snowed, and to make matters worse, we ran out of rations,” he recalled. Military brass told soldiers to live off the land, not wanting to risk a German interception of dropped rations. “Well, the farmer had left,” Tangherlini said. “High up where the farmhouse was, there were hutches for rabbits, and there were live rabbits.” They ate the rabbits.

He was also sustained by memories of watching Marlene Dietrich perform, he said. He recalled seeing her twice with the U.S.O. (United Service Organizations): once stateside and again in France shortly before he deployed to Belgium.

Tangherlini experienced the German presence in Bastogne as a quiet menace, shrouded and muted by snow and woods. He was an assistant machine gunner, staying vigilant as he watched over a road heading into the woods. “We had an armored German car come up that road,” he said, “and they launched a couple of rockets at them, but we were cautioned not to fire. We didn’t want them to know how much we had.”

After a grueling two weeks of cold and no showers, General Patton’s Third Army broke the siege with reinforcements, and Tangherlini was redeployed. He worked as an interpreter in Alsace, since he spoke some German, and transported radios to Allied headquarters there under shelling.

There was still the Battle of Alsace and an assault into the Rhineland to go before Tangherlini received an honorable discharge and joined a parade on New York’s Fifth Avenue — in January 1946.

Once he’d left the service, Tangherlini resumed his career in science. The advent of the nuclear age, he said, and the atomic bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki helped to concentrate his interest in physics.

In the early 1950s, he helped engineer guidance and control systems for the earliest ICBMs at the Convair Division of General Dynamics in San Diego — work that he said was sometimes uncomfortable, not only because of the product but also because the research involved collaborating with former German scientists. His supervisor, Walter Schwidetsky, had helped to design V2 rockets in the Nazis’ Peenemünde facility.

“One day, he said, ‘Frank, when I was at Peenemünde, you could see some of those parts were made with real love,’ ” Tangherlini recalled. “I said, ‘Walter, when I was in Europe, some of that love was coming my way.’

“That’s the fortunes of war,” Tangherlini said.

The ‘Tangherlini Transformation’

He left that work to pursue his Ph.D. “on some of the fundamental ideas in special relativity, like the relativity of simultaneity.”

Typically, in special relativity, the speed of light is measured as constant; simultaneity is relative. But what if, Tangherlini theorized, some particles traveled even faster than the speed of light?

He imagined two clocks traveling faster than the speed of light that could nonetheless be synchronized with each other. That idea would tilt the typical equation, Tangherlini said: “Simultaneity is absolute. The speed of light very much depends on the frame of reference.”

The idea came to be called a “Tangherlini transformation” and helped inform the theory of a hypothetical particle called a tachyon. In other widely cited contributions to general relativity, Tangherlini’s theories have helped inform black holes theory in multidimensional spacetime.

In Wellfleet last Friday, Tangherlini grasped the M1 rifle gingerly. “It feels much heavier than when I was a soldier,” he said. Since the war, he said, he had maintained an interest in nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament. But now, the promise of world cooperation seems to be falling short, he said.

“I’m frankly a little pissed off at the human race,” he said. “I’m disappointed with the way things have developed, both with respect to the Russian-Ukrainian war and also the Israeli-Gaza war.”

He understood that fighting instinct, he said, which tells one “if you don’t fight back, you get eaten.” But “they’re killing everyone,” he said. “If we cooperate, think what we could do.”