EASTHAM — Property taxes have been in the spotlight in Eastham this year. In the annual town election, two candidates for select board told the Independent that rising taxes were the biggest issue facing the town, while at town meeting, the citizen-petitioned Article 9A asked the select board to hire an outside auditor to assess the town’s tax strategy.

Those two candidates, Dave Hobbs and Brian Earley, were defeated by incumbents Jerry Cerasale and Suzanne Bryan, and Article 9A was defeated as well.

Nonetheless, with an expensive wastewater project coming ever closer to reality here, a focus on the bottom line seems easy to understand.

“In towns that go to town meeting, there’s a focus on property taxes,” said Phineas Baxandall, a senior analyst at the Mass. Budget and Policy Center. “Pretty much anyone who votes in town meeting knows what’s happening with their property tax rate.”

Property taxes aren’t the only taxes Eastham residents pay, Baxandall said, but they’re the ones voters have the most control over, so they get a lot of attention.

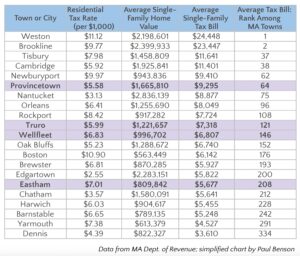

Some residents have complained at select board meetings that the town’s residential tax rate is higher than those in Wellfleet, Truro, and Provincetown: Eastham’s was $7.01 per $1,000 of assessed value in fiscal 2024 compared to Wellfleet’s $6.83, Truro’s $5.99, and Provincetown’s $5.58 in that same year.

But when it comes to the amount that homeowners actually pay, Eastham’s average tax bill is significantly lower than those of its neighbors. Based on reports from the state Dept. of Revenue, the average single-family residence tax bill in Eastham was $5,677 in fiscal 2024 compared to Wellfleet’s $6,807, Truro’s $7,318, and Provincetown’s $9,295.

That’s largely due to Eastham’s lower property values, said Finance Director and Assistant Town Administrator Rich Bienvenue. Because the average property value in Wellfleet, Truro, and Provincetown is higher than in Eastham, the lower tax rate in those towns still results in a higher average tax burden.

“The burden is the important thing,” Bienvenue said, while “the rate is a byproduct” of assessed residential values.

Eastham’s tax burden is relatively low compared to other towns in the state, too. The average tax bill is significantly higher in Orleans, Nantucket, and Cambridge; about the same in Brewster, Chatham, and Harwich; and significantly lower in Dennis and Yarmouth.

Overall, Eastham’s tax burden was ranked 208th out of 351 Massachusetts towns in fiscal 2024.

Rising Property Values

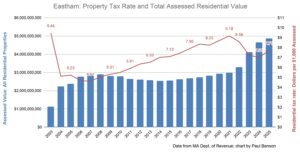

While property values have increased dramatically in recent years, Bienvenue and Baxandall both pointed out that rising assessments don’t automatically increase the town’s total tax revenue or the average tax bill. “In theory, if the price of real estate goes up, that allows the tax rate to go down and collect the same amount of taxes,” Baxandall says.

The town’s actual tax levy is set by town meeting voters, and its rise is controlled by the state’s Proposition 2½ law, which was passed in 1980.

Rising property values do increase a town’s “tax levy ceiling” — the absolute maximum amount that can be raised through taxes, including through Proposition 2½ overrides. The levy ceiling is equal to 2.5 percent of the total assessed value of a town’s property, but Baxandall said it’s exceedingly rare for a town to hit that ceiling.

Instead, rising assessments can put financial strain on residents when not all properties increase at the same rate.

Waterfront property, for example, can surge in assessed value even when other properties remain stagnant, causing those owners to pay a greater share of the town’s total tax levy.

“If somebody’s seen their property values increase a lot, on the one hand, that’s fantastic — for many people, their property is their biggest asset,” Baxandall said. “But from a year-to-year point of view, it’s possible they’re getting taxed more.”

Rising property values can also make it hard for working-class people who live elsewhere to move to the Cape, Baxandall says, which raises the overall cost of living.

“Because people can’t afford to live here, we have to pay workers to travel here from somewhere else,” Baxandall said. “The explanation for almost everything goes back to properties being too expensive” for working people to afford.

How Taxes Go Up

Tax burdens can also rise regardless of what’s happening with assessed property values when voters approve budget increases, operating overrides, and debt exclusions at town meeting. Those budget increases raise the overall tax burden that is divided among all property owners, with overrides authorizing a permanent increase and debt exclusions a temporary one.

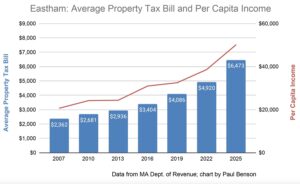

In Eastham, the increase in the average homeowner’s tax burden over the last 20 years has largely tracked a rise in per capita income here, according to Dept. of Revenue data. The salaries and wages paid to town staff have increased, and the costs of construction projects have increased, but average local incomes have increased at about the same rate, that data shows.

“If the bills are outpacing people’s ability to pay them, then that’s a problem,” Baxandall said. “But the data indicates that, at least to some extent, it’s the opposite.”

Bienvenue has also measured the changing tax burden relative to federal inflation statistics and the annual increases given to people who receive Social Security. Since 2016, payments to Social Security beneficiaries have increased at only about one-third the rate that taxes and per-capita incomes in Eastham have — which is why seniors are a population of special concern when it comes to property taxes.

Capital Expenses

When it comes to the overall tax picture, Bienvenue said a significant part of the burden on taxpayers is due to capital projects, including the water system Eastham voters approved in 2014 and 2015, which had a final cost of $130.8 million.

In fiscal 2016, the average single-family residential tax burden was $3,404. Adjusted for inflation and nothing else, that number would have been $4,532 in fiscal 2024, Bienvenue said. But debt service for the town water project caused the overall tax burden to spike. Bienvenue said major infrastructure projects have driven up tax burdens in other towns, too.

Town water didn’t have to cost so much, Bienvenue said. In 2007, when a $76-million proposal for a town-wide water system failed at town meeting, Eastham lost an opportunity for zero percent loans from the state to fund the project.

The project was priced at $114 million in 2013 and failed again. By the time the water system was finally approved, it cost $54.8 million more than the 2007 proposal, not counting the higher interest costs the town had to pay.

Bienvenue estimates those added interest costs at about $70 million in payments over the 30-year life of the loans.

On June 24, town meeting voters will debate whether to accept a $50-million zero-interest loan from the State Revolving Fund to fund the construction of a municipal sewer system. This year’s loan terms include “automatic renewal” — allowing the town to access zero-interest funding for many years to come — and it’s not clear if next year’s loan program will include that feature.

Bienvenue said the vote is “a consequential decision” for future tax rates.