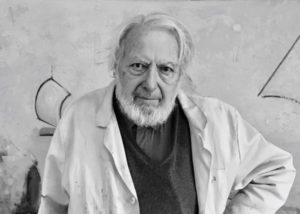

Paul Resika was browsing in a bookshop in New York City when he came across four volumes of engravings of paintings in the Vatican Museums. He bought the whole set for a few dollars — and put them in a closet in his studio. “I didn’t know what to do with them,” he says.

About three years ago, he had an idea. “I thought, ‘My God, I could make hundreds of paintings from these things,’ ” he says.

Resika’s latest show at Berta Walker Gallery uses one of the engravings as a point of departure for an entire body of work. The engraving is based on part of an altarpiece painted by Fra Angelico in 1437 depicting a miracle attributed to the 4th-century Saint Nicholas of Bari. When a ship filled with grain stopped in the port of the city where Nicholas lived, he petitioned the port officials to leave some of the grain behind to help relieve a famine in the city instead of sending it on to the emperor in Constantinople. The future saint promised the sailors in charge of the shipment that they would not be punished for delivering less grain than the emperor was expecting — and his promise was miraculously fulfilled when they later arrived in Constantinople with a full load of grain despite having diverted some of it to feed the hungry.

The monochrome engraving lacks the dramatic color of Fra Angelico’s painting, and so dilutes the sense of the miraculous in the original. Instead, the image emphasizes the more mundane aspects of the composition: the ships on a turbulent sea, workers loading bags of grain, and the gestures of Nicholas as he talks to the officials.

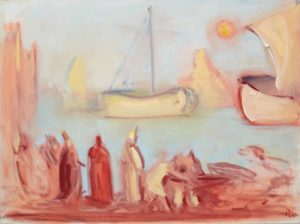

Resika reimagines the scene in a visual game of telephone played across centuries. His interpretation reignites Fra Angelico’s miraculous vision by reducing elements of the composition and balancing them in open, luminous fields of color, pregnant with mystery.

But the original painting was less an inspiration than a point of departure. “I don’t think I thought about Fra Angelico,” says Resika. Instead, his work is animated by decades of experience painting from nature and the influence of artists like Hans Hofmann (with whom Resika studied) and Mark Rothko.

The exhibition provides an intimate view of an artist’s working method. In a 2019 monograph on Resika’s nearly eight decades of creative output, art historian Avis Berman says that Resika’s process involves “variants and serial approaches to an idea.” This process is evident in this installation, which includes the original engraving, Resika’s initial sketches, his small oil studies of the subject, and the large paintings in which his response is fully formed. It’s a fascinating study in the unspooling of a creative vision, sharpened by Resika’s fixation on one idea.

It’s also consistent with Resika’s paintings of Provincetown wharves, some of which are on view in an adjacent gallery space. “Every day, I was in the harbor at the same hour for three or four months of the year,” he says. The continual act of looking resulted in a distillation of form: elements are reduced to their most basic shapes, allowing light, color, and atmosphere to take center stage. In the luscious Pier at Night, boats and a shack seem to melt into an atmosphere of nocturnal blues.

By circling around his subjects, Resika reduces a picture to a limited range of elements — and in doing so creates his own compositional vocabulary. The most prominent forms in the current series are a group of three robed figures, various triangles, and a circle. Locating the sources of those forms in the original engraving feels like a game: an arched triangle began as a coastal cliff; the circle, a divine figure in the sky.

Resika himself uses play as a metaphor to describe one of the most abstract paintings in the show, which he likens to a pinball machine. In Allegory (San Nicola di Bari) #12, two triangular shapes, a circle, and a vertical rectangle sit on a blue field. Like a ball navigating through obstacles on the surface of a plane, the viewer’s eyes move in a circular motion around the shapes. A sense of depth is created through a Hofmann-like tension between a dark blue rectangle at the bottom of the painting and the sunny, white triangle that recedes into the background.

“It’s not flat like Albers,” Resika says, noting that the spatial tension keeps the picture alive.

There’s also a profound sense of feeling in the paintings that exists beside their eloquent formal play. Echoing the miraculous narrative of the original, Resika imbues his paintings with religious imagery, from the cruciform shapes of sailboat rigging to the three men who appear as priestly figures as the series develops. Resika sees a parallel function between priests and artists: “Religion and art go together,” he says.

And while Resika’s paintings embody the distillation of forms, they also involve their dissolution — a quality that most overtly suggests the metaphysical aspect of his work. With no horizon line in most of the paintings, there is no ground upon which to stabilize oneself. The scale of the large paintings and their monochromatic fields of blue, red, and orange immerse the viewer in atmosphere, an effect derived through Resika’s outdoor landscape painting practice. Shapes and figures serve as reference points, but seem only tentatively anchored to reality. The viewer is left to find his own place in the cosmos.

This mysterious process culminates in Allegory (San Nicola di Bari) #14, in which the three figures stand underneath a white orb against an expanse of red. Form dissolves into material, while ghostly shapes hover underneath the surface. The edges of the canvas are left unfinished. And the three men, existentially bare under the sun, are the only guides we have, leading us away from our comfortable moorings of reality and toward the miraculous: a journey not unlike that of Saint Nicholas himself.

Allegory (San Nicola di Bari)

The event: An exhibition of paintings by Paul Resika

The time: Through Sept. 17

The place: Berta Walker Gallery, 208 Bradford St. #1, Provincetown

The cost: Free