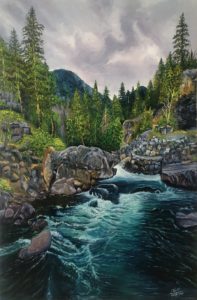

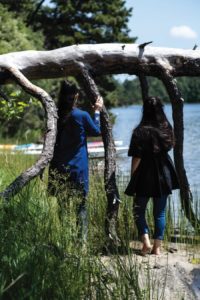

WELLFLEET — Maryam and Shabnam have been enjoying a typical Outer Cape summer — going to Newcomb Hollow Beach and the Fox and Crow Café and on whale watch excursions —all the normal pleasures of the season that tourists and locals savor.

But the two sisters are neither tourists nor locals. They are young women who fled Afghanistan and, after living for 18 months in India, have made it to Wellfleet with the help of David Simpson and Kathy Fletcher, at whose home they are living and where they were interviewed for this article. Both speak English well.

Maryam and Shabnam — whose names have been changed to protect other members of their family who remain in Afghanistan — were born in 2001 and 2003, respectively, in Badakhshan, a province in the northeastern region of the country. They lived in a small house in a rural area with their father, mother, and four siblings.

In 2005, the family moved to a different province in northern Afghanistan to pursue better educational opportunities. Maryam and Shabnam grew up there, enjoying a relatively peaceful childhood — the Taliban was not yet a serious threat. Their father owned a small grocery store where Maryam started working when she was eight.

The family is progressive by Afghan standards — the parents believe in equal rights and educational opportunities for women. Shabnam says their older brother had a lot to do with those unconventional beliefs: he studied in France and when he came home he broadened his family’s ideas about culture, tradition, and customs.

Maryam’s brother taught her to ride a bicycle when she was 12 and she loved it. She would ride her bike to school and to her father’s shop, sometimes doing laps back and forth just for fun.

But there was a mosque along the road, and people began to notice her riding. They disapproved. A religious scholar at the mosque contacted Maryam’s father and told him, “She’s a girl and she shouldn’t ride a bicycle,” she says. “It is just for boys. It is a shame.”

Their father responded that Maryam was just a child and that she deserved the same opportunities and rights as his sons.

In 2015 the Taliban took control of the province where the family was living. There were robberies and killings, and women were raped, Shabnam says. The family moved to Kabul, the capital, which at the time was free from Taliban control.

The sisters continued their education in the city, taking courses at a public high school. Both graduated at age 15 in 2016 and 2018. Maryam had passed exams to skip two grades in school, and Shabnam had enrolled at age four with her older sister.

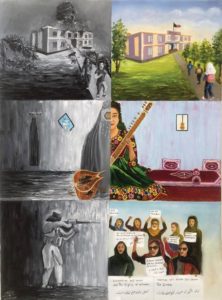

After graduation, Maryam went on to art school in Kabul. As a child, she loved to draw almonds, which were plentiful in her hometown — but this was her first opportunity for professional training beyond her high school art class.

In 2020, Shabnam entered university to study journalism. She also worked concurrently as a reporter for a national news organization in Afghanistan. “My stories were mostly about suicide bombings, explosions, and violence against women,” Shabnam says. “That’s all there was to write about.”

In late 2019, while Maryam was still in art school, she opened a gallery with a fellow student. But “it was not long until something went wrong,” she wrote in a statement to the Independent. One morning, Maryam noticed an envelope taped to the gallery door. It was from the Taliban. Written in Pashto, Maryam wrote, the letter said, “This letter is for guiding you to a right way. You know painting is against the Islam religion roles. Close your gallery immediately and do not mislead the people.”

Maryam and her partner didn’t take the letter seriously, not believing it was really from the Taliban. But soon they received another letter, and one day when Maryam was leaving the gallery two men approached her.

“One of them put his hand on my shoulder and said: ‘Daughter of the dog, if I see you here again I will kill all of your family,’ ” Maryam wrote. “It was the most frightening moment of my entire life.”

Maryam was forced to close her gallery and work on art projects only in school and at home. Soon after that, even school became too dangerous, so Maryam was housebound.

Maryam began to receive calls from the Taliban threatening her and her family. Later that year, the father of Maryam’s gallery partner was assassinated by the Taliban. “My partner says they killed his father because I am an artist,” Maryam wrote. “I was devastated and terrified.”

At the same time, Shabnam abandoned her job as a reporter and began online classes to stay safe at home. The sisters spent long hours at home each day, calling friends and playing cards and a board game called Carrom.

“There wasn’t anything for fun,” Shabnam says. “Women couldn’t go for walks — no parks.”

Shabnam says that, although there were still sports and other activities, their family was too scared to go. “If you go there,” she says, “explosions will happen.”

The Taliban Closes In

In January 2021, Maryam and Shabnam obtained student visas to study in India, and they fled their home country.

The family was still in danger, though. Although their father had been sending them money for living expenses, when Kabul fell to the Taliban in August he lost his job selling pistachios and dried fruits.

The family traveled back to their home province of Badakhshan, where they thought the Taliban wasn’t as powerful. But it was not long before they were tracked down.

“In our village, everyone knows us,” Shabnam says. “Because we were the first family to go from our village to a city to get an education. The Taliban asked my father, ‘Where are your two other daughters?’ ” The Taliban suspected they were studying abroad and thus violating Islamic law. Her father made up an excuse: “My father said, ‘My daughter Shabnam has cancer, and Maryam is looking after her,’ ” Shabnam says.

As punishment for allowing his daughters to travel, the Taliban demanded that their father buy them weapons, Shabnam says. He refused, instead offering the Taliban his land. He promised his daughters would be back once flights that had been paused due to the pandemic resumed — a promise he had no intention of keeping.

After that incident, the sisters’ father went into hiding, so they were unable to contact him. He also could not send them money, leaving them with no income.

A Fortunate Introduction

That’s when the sisters were introduced to Fletcher and Simpson, the Wellfleet couple who created AOK — a nonprofit that helps artistic youth from underprivileged backgrounds. Fletcher is also executive director of the nonprofit music organization Silkroad, which had been helping Maryam’s friend, a sitar player, escape Afghanistan. Once she was safely in Portugal, the friend told Silkroad about Maryam and Shabnam.

With funding from Silkroad and AOK, Fletcher and Simpson helped Maryam and Shabnam find their way to the U.S. They applied for emergency permission to travel here in September but hadn’t heard anything by May. Because their Indian visas were expiring at the end of June, Maryam and Shabnam were increasingly worried — Afghanistan was even more dangerous than when they had left.

Then they were admitted to a three-month English language program at Boston University, which allowed them to apply for student visas.

Those were approved within two weeks, and on June 29 Maryam and Shabnam flew to Boston, where they were picked up by Fletcher and Simpson, who drove them to their new home in Wellfleet.

The sisters have been here since then. Their summer, while sweet, has been tinged with worry. Their family is still in Afghanistan, where conditions are getting worse. Maryam and Shabnam worry especially about their father, who was targeted by the Taliban last year. They are afraid the Taliban will realize he was lying about Shabnam’s cancer and will kill him.

Maryam and Shabnam are working on applications for asylum so that they can stay beyond the one year their student visas give them in the U.S. Once their asylum applications are approved, they hope it will be easier to secure student or medical visas to bring their family to Wellfleet.

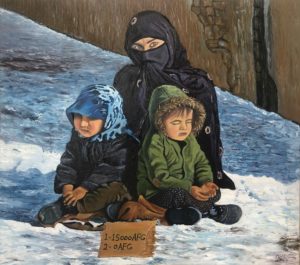

After that, Maryam and Shabnam hope to pursue their dreams. Maryam wants to open an art gallery in the U.S. and teach art to children. She also hopes to work as a professional artist, selling her paintings and using the proceeds to help others like her.

“Through my paintings, I will help those who need help in Afghanistan,” she says.

Shabnam plans to be a journalist. “I want to be the voice of Afghan women,” she says. “They are voiceless.”

AOK is holding an event at Wellfleet Preservation Hall on Thursday, Aug. 25 at 5 p.m. called “In Support of Afghan Artists: A Special Author Event” to assist Maryam and Shabnam in their efforts to help their family escape Afghanistan. For more information, write [email protected].