Even in our current predicament, there’s no stopping nature. The daffodils have come and gone, and now the beach plum is fully abloom. The lilacs have begun to release their fragrance and the lily of the valley will soon follow. All remind us that, no matter what winter piles on, a sturdy and resilient spirit wins the day.

Another returnee is the Oriental poppy, Papaver orientale, a hardy perennial whose dazzling, solitary orange-red flower adds an old-fashioned exuberant charm to the garden. Its rebirth begins inconspicuously as a cluster of hairy leaves emerging from the still-cold ground. The leaves thicken, stiffen, and multiply, and from somewhere deep in their midst comes the sturdy stalk that will grow several feet high, supporting a tightly packed nodding bud. As the seams of the calyx begin to separate, the first hints of the tissue-papery petals will show themselves.

If there is anything disappointing about the full-faced flower and its dark, velvety eye it is its ephemeral nature. Blink and you’ll miss the unfolding of the petals. Blink again and the slightest breeze will have robbed the flower of those petals, leaving only the seed pod. I cut the dry pods every fall, shake the tiny seeds from within, and arrange them in a vase as an elegant winter reminder that warmer days are ahead.

The poppy is legendary for the narcotic effects of some species, particularly Papaver somniferum, the opium poppy, known by the ancient Sumerians as the “joy plant.” Ancient Egyptians buried their dead with the poppy to ensure a peaceful sleep. In Greek mythology, Demeter created the poppy to induce sleep after the abduction of her daughter, Persephone.

If the scourge of addiction brought attention to the opium poppy, the scourge of war brought attention to another member of the family, Papaver rhoeas, the common red poppy. Also known as a field or corn poppy, the wildflower contains rhoeadine, a nonpoisonous mild narcotic. Greek legend tells of this poppy being created by Somnus, the god of sleep. Its seeds, which can lie dormant for years, germinate in rooted-up soil. Profusions of the graceful flower beautify and transform sunny wastes and old fields, though some regard Papaver rhoeas as little more than a weed and the target of herbicides.

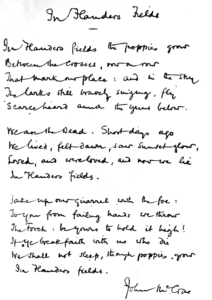

To Lt. Col. John McCrae, a Canadian surgeon attached to the 1st Field Artillery Brigade in western Belgium during World War I, the dainty poppy became a symbol of the terrible toll of war. For 17 days, McCrae tended to the injured in the Ypres Salient, an experience he later wrote was “17 days of Hades.” During lulls in the ferocious fighting, the dead were buried where they fell, amid the rubble and blood-soaked soil, their graves marked with wooden crosses, row on row. One death particularly affected McCrae. A young soldier, Alexis Helmer of Ottawa, whom McCrae had befriended, was killed on May 2, 1915. In the absence of a chaplain, McCrae performed the funeral ceremony. The next day, an anguished McCrae composed the poem “In Flanders Fields,” perhaps the most memorable words ever written about war.

All around him, on the battlefield that had become a cemetery, the little red poppies, whose roots were said to feed on blood, mysteriously blossomed over the graves of the fallen, a phenomenon that had also been noted a century earlier during the Napoleonic Wars. McCrae wrote the poem in 20 minutes, describing the scene before his eyes at Ypres, then tossed the page aside. Retrieved by a fellow officer, the poem was sent to newspapers in England and was eventually published in the magazine Punch.

Not long afterward, McCrae was transferred to a hospital in France, where he served as chief of medical services. He died there on Jan. 28, 1918, officially of pneumonia and meningitis, but most likely from complications caused by the 1918 flu pandemic.

Inspired by McCrae’s poem, an American woman, Moina Michael, was the first to wear a poppy in honor of those who had died in the nation’s service. The tradition spread to other countries and in 1922 the Veterans of Foreign Wars became the first organization to adopt the poppy as a symbol of remembrance and Memorial Day. Today, paper poppies, assembled by disabled and aging veterans, are sold to benefit veterans’ services.

Inspired by McCrae’s poem, an American woman, Moina Michael, was the first to wear a poppy in honor of those who had died in the nation’s service. The tradition spread to other countries and in 1922 the Veterans of Foreign Wars became the first organization to adopt the poppy as a symbol of remembrance and Memorial Day. Today, paper poppies, assembled by disabled and aging veterans, are sold to benefit veterans’ services.

It has been more than a century — and a world of change — since Lt. Col. McCrae wrote his poem, with its haunting evocation of lost lives. But his words remain a lasting legacy of the horrific battle of Ypres and a poignant reminder to those of us who live on that we, now, speak for the dead.

To you, from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.