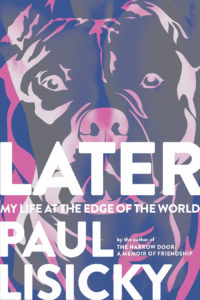

Paul Lisicky could not have known that his newest book would be released in the midst of a global pandemic. And yet it’s apropos that the publication of Later: My Life at the End of the World should coincide with the Covid-19 outbreak. Lisicky’s fifth book, Later chronicles the author’s life in Provincetown during the HIV/AIDS crisis of the 1990s. It’s strangely comforting to read this memoir of solidarity, struggle, and self-discovery in the current moment of heightened awareness of the fragility of human life.

“Covid-19 is really different from the HIV/AIDS crisis, but people seem to be connecting to the book in a way that they might not have in a less charged moment,” says Lisicky, speaking by phone from his Brooklyn apartment. (Lisicky did a virtual reading from the book for East End Books Ptown on March 27.) “It seems to be useful and helpful to people and I’m enormously grateful for that.”

Later traces Lisicky’s relationship with Provincetown from his first arrival in 1991 as a Fine Arts Work Center writing fellow. Told in a series of vignettes, the memoir follows Lisicky’s exploration of both the external life of the town and his own internal landscape. It’s a collage of feeling states and self-discovery. We follow the narrator through his anxious early days of becoming a writer, with all the attendant self-doubts, and through the blossoming of his sexuality, the thrills of romance, and the long road to self-acceptance.

When he first arrives, he’s anxious, still wearing J. Crew barn coats, unsure how to slough off the constraints of a suburban, not-so-happy childhood and the years of college and grad school, when, as Lisicky says in conversation, “It wasn’t cool to be gay, and it didn’t feel very safe.”

In Provincetown, he finds that though it’s very, very cool to be gay, safety is still elusive, as friends and lovers battle HIV-positive diagnoses, AIDS-related illness, and death. In the relative freedom of his new home, he can learn about what he wants and who he is through dating and hookups. Yet these encounters heighten his awareness of how perilous it still is to be gay. “He’s positive” is a whisper that runs throughout the book, and no one is unscathed.

It’s hard not to recall the cynicism with which gay men suffering from AIDS were treated for so long. Early in the book, Lisicky asks, “Would AIDS be a different beast if you could catch it from the air-conditioning, or by a sneeze or subway pole, a public swimming pool?” Based on what we’re seeing with Covid-19, the answer is both yes and no. That the current pandemic has struck so many people across national, economic, and social divisions drives a swifter public response with less shame for those afflicted. Still, as Lisicky reminds us, those on the margins — people of color, the poor, those with disabilities, without family — are hit first and hardest.

Like Provincetown itself, Later is a book that holds contradictions. “The Provincetown of Freedom rubs up against the Provincetown of Restraint,” writes Lisicky. Buttoned-up yards and pristine 19th-century cottages rub up against steamy encounters in clubs and on beaches, and Midwestern tourists provide a necessary counterpoint to drag queens rambling down the street in six-inch stilettos. The natural wildness of the Cape, where ocean storms continually shift and shape the land, is analogous to the inner, human wildness that runs through each of us as we navigate oscillating desires for freedom and safety.

“I’m interested in what goes on in the interior life during these moments, even moments that at the time might not seem so profound,” Lisicky says. “I haven’t found that internal theater represented in much literature. Sex can be this arena of escape, but even when we escape, we’re still thinking and wondering. There’s a lot of complexity that goes into those charged situations.”

Lisicky says he worked consciously to build that complexity into the book’s structure and prose style. “I was writing about things that were 30 years past,” he explains. “The book is a collection of pivotal moments or pressure points where I was learning something or losing something or both.”

Lisicky first started working seriously on Later in 2016. “The first draft was in the past tense, super-linear,” he says. “After a while, the past tense started to feel too neat or resolved. It felt like the book couldn’t be in 4/4 time. It needed to be speedy in some sections and slowed down in others. It needed to shift meter from time to time.”

There’s too much collective trauma in Later for anything like a happy ending. Still, Lisicky’s book offers insight into how moments of crisis also provide opportunity. We see the networks of care among friends and lovers with AIDS, among writers who cheer each other on, among the inhabitants of a small misfit town who break up, make up, gossip, and squabble, but ultimately show up for each other again and again.

In the book’s epilogue, aptly titled “Afterlife, Notes,” the present-day Paul is haunted by the ghosts of those who have died, but he’s also living and loving, shaped by both losses and gains. Self-knowledge, Lisicky says, “is an ongoing project. Even when you’re older than you once were, you’re still discovering things. My younger self would never have wanted or expected the life I have now. It’s really wonderful.”

Looking back on his younger self, Lisicky says, “I think that younger person thought there were very few options for fulfillment. But life is so much more complicated than that. I’d tell my younger self to be alert and awake, because that’s where life is. It’s in curiosity, not just toward ourselves and other people, but to our feelings and reactions. Experience is a book. It’s meant to be inhabited and questioned.” He pauses, laughs. “And then, my younger self would roll his eyes and say, ‘Yeah, right. Find me a boyfriend!’ ”