Akiko Jackson is a second-year visual arts fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown. Her first fellowship year was 2013-14; the day she returned, this past October, Jackson says that Bob Bailey, the center’s facilities manager and one of her favorite people, called out to her.

“Hey, Akiko,” Bailey said. “I think it’s time for you to set down some roots here.”

“You must have read my mind,” Jackson replied. “I actually want to stay here as long as I can beyond the fellowship. I really love it out here.”

Temporarily, at least, that wish may become a reality, though not under the best of circumstances. Jackson, whose solo show, scheduled to open on April 3, was canceled due to the Covid-19 crisis, is currently completing her last month of residency. She’s sheltering in place with the other fellows, while the work center’s common areas are closed, as is much of the town. With most of her future plans canceled or postponed, Jackson has nowhere to go at the end of April.

“Everyone is sequestered in their apartments and studios for the duration,” FAWC Executive Director Richard MacMillan told the Independent. “Once the seven-month fellowship ends, the residences will be open to them through June 15. They’ll be able to live in their apartments and work in their studios.” MacMillan added that he intends to meet personally with each of the fellows to ease their transition.

“A situation like this consumes your mind,” Jackson says. “It makes you wonder — how can I work during such a time? People often say of difficult times that this is when we need the arts the most. And that’s true. But it is also true that artists are crippled by the hard times.”

Jackson intends to use whatever time she still has here to work in her studio. “In the studio is where I allow myself to be in a different reality,” she says. “I didn’t expect, though, how difficult it would be not to be able to stand near a friend, not be able to hug one another. This physical separation adds to my psychological isolation.”

Jackson grew up in Kahuku, a rural community on the northern coast of Oahu, in Hawaii. “My formative years were there, my accent is from there, my spirit is from there, and my memories and longing will always be from there,” she says. But she adds that she moved away from Hawaii many years ago and no longer has close family there or a home to return to. Her upbringing in a lower socioeconomic household and community, Jackson says, made her value intangible things like loyalty and friendship, good food, laughter, “and the uncomfortable things like sharing hard stories and grief together.” She feels that she has found those intangibles at the work center and in Provincetown. “The six years of being away from P’town, experiencing a lot of adversity and heartbreak in other places, made me remember how important it is to have solid friendships you can count on,” she says.

In her art — for the most part, large-scale sculptures and installations in black — Jackson seeks to confront difficult memories. “My thoughts are consumed by how vulnerable we are when faced with death,” she says. “Because we don’t talk about this frequently, or at all, there’s a certain kind of discomfort we often can’t tap into. A few years ago, I witnessed my grandmother’s death, alone. I carry a lot of pain from that experience.”

Jackson, whose mother is Japanese, incorporates symbolism in her sculpture from ancient Japanese rituals and shrines to commemorate the dead. “In one installation,” she says, “I’ve incorporated forms reminiscent of butsudan doors, which protect a person’s ashes, a family’s ancestors, food offerings, and such.”

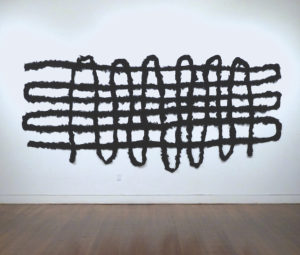

She has also been working on “drawings” sculpted from wool, ropes, nets, and plastic detritus collected on local beaches. “I use wool to create versatile forms, referencing the transformation of an old tradition of creating fabric into a contemporary process for sculpture,” she says. “Working with Japanese traditions passed on to me by my mother, I’m pressing, rubbing, hitting, and tangling to create soft sculpture by bonding many loose hairs together.”

In Jackson’s sculpture, hair frequently becomes a metaphor for the embedded histories we carry with us. “Hair is the outer layer, a protective surface, and a signifier of the body in my work,” she says. “Pain, suffering, loss, and mourning are all very real, but they are the invisible realities our bodies carry.”

Jackson was introduced to the problem of cast-off debris by the Center for Coastal Studies early in her fellowship. “I had a visceral response to seeing the enormous quantity of cast nets, ropes, hand lines, trolling, plastics, cordage — all death traps released into our oceans,” she says. “Being from an island, I have a lot of memories of cleaning the beaches from this manmade destruction. Imagine swimming in the ocean and your foot or body gets caught in some kind of invisible cloud. It’s incredibly scary to me, and it’s part of my paralyzing nightmares. There’s a term for it — ghost nets. You become entangled, suffocate, ripped to shreds. This is what happens to life in the ocean.”

Jackson says that her time in Provincetown has been remarkably productive. “Feeling at home is the best fuel for my work,” she says. “I’ve come to realize at this time in my life, that is a rare privilege I haven’t had in many years.”