The loveliest thing about periodic cicadas is their red eyes. Their wings are mottled in golden brown, like precious metal, lace over ebony. Certain insects become jewelry: scarab beetles, dragonflies, cicadas. No surprise they are called Magicicada.

Of the 3,000 known species of cicadas worldwide, only seven are periodic — there are 13-year and 17-year broods. Most other cicadas spend just a year or so underground, with stragglers and early emergents throwing off the cycle and possibly enriching the gene pool.

Humans are forever looking for signs in nature. So, we wonder if the cicadas’ emergence is a plague or a marvel.

We might prefer nature clean, edged within concrete curbs. But while nature is not messy, it’s blind to our boundaries. There may be a half million cicadas per acre, but scientists shrug and ask, why not? How many ants are there in an acre? How many butterflies?

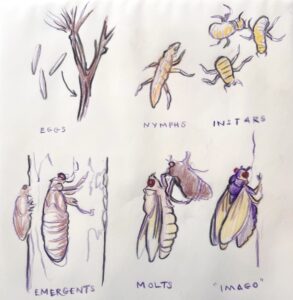

During their years underground, where they burrow up to eight feet deep, the cicadas aren’t asleep: they grow through five different nymph stages, and when the soil warms, they emerge just after sunset. They feed on living twigs of trees and shrubs; grasses will not do to sustain them.

After such a long prologue, cicadas live less than a month from the moment they first see daylight. Long enough to swarm and drone unique songs to attract mates. Their scarlet eyes are sun goggles, appearing after a long life underground. Their flight is clumsy; they are poor at hopping.

Imagine all those years in darkness, emerging with so little time to learn how to use your wings, brief freedom for the urgency of mating to ensure the species lives on.

Once they’ve laid their eggs, they’re gone; their oversized bodies ooze, then dry out, leaving elaborate shiny husks. We encounter their ruins with a sense of loss. Like the kind evoked by the poet Shelley when he imagines the sorrow of Ozymandias, an unknown fallen god. Nature gives brief flashes of beauty and leaves us to wonder what it was for.

In China, cicadas decorated emperors’ crowns. They were considered pure and sharp-eyed. They lived on dew. There, as early as 100 B.C.E., jade cicadas were placed on the tongues of corpses.

Cicadas drone in rhythm like a Philip Glass rondo that can either be meditative or maddening. The buzzing is a song, and every species has a different one. Their droning is a reminder of how time works. Our own lives unfold during the cicadas’ 17-year sleep. Try to recall your whereabouts in 2008 and your hopes for 2042. They last emerged during a financial collapse, but we regained our footing, living with new caution if not wisdom.

In those years, I became an artist, I traveled beyond my imagination, lost family members and friends, had relationships. I grew a shiny exoskeleton of achievements, staying soft and unformed inside in ways the world can’t see.

Eggs laid in cracks of bark hatch quickly; the nymphs fall to the earth and burrow down for another generation’s long night.

We might think of this 17-year periodicity as a lifestyle. And animals are entrepreneurs, each finding a niche in nature to produce and exchange their special assets — food and song and lively new generations of singers. Or the cicadas’ long night could be a way to avoid the paths of glaciers or wait out an abundance of blackbirds: a cautionary act, a way to stretch time.

As for me, I hope to be awake in 2050, the year of net-zero, to see what part of the world is under water, to see how we decided to live.