We are more than halfway through April, and the air is already full of birdsong. It seems every other bush in town hosts a song sparrow, lustily bellowing his qualifications into the air to echo and outcompete his neighbor. And there are hosts of cardinals, wrens, titmice, mourning doves, chickadees, house finches, and more, all pouring forth their libidinous calls to procreate. Now add to this wild symphony a loud croak — a decidedly unbirdlike croak.

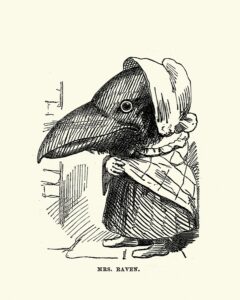

We are talking about the new bird in town, the common raven (Corvus corax). When I say new, I mean relatively so — in the last decade or so — and when I say in town, I mean setting down stakes here, i.e. nesting, or at least trying to do so.

You have probably seen or heard this bird and, unless you are a birder, not taken notice. In appearance, it is very similar to our everyday crow (we actually have two species of crows) but bigger, with a larger head and bill and a larger wedge-shaped tail. It is often seen high in the sky, soaring like a hawk or vulture. If you’re not a birder, you will be excused for not being able to distinguish this bird from its smaller cousins. But think now if you might have heard its distinctive croak, or what the Sibley bird guide describes as “deep baritone croaks to high, bell-like twanging notes … hoarse … resonant.” Does that ring any bells?

If you think about ravens at all, you might associate them with the Western states, where their croaks resonate off canyon walls, or up north, or down in the Appalachian Mountains. But ravens have been dramatically increasing their range and are ever more noticeable on the Cape.

The first raven nest was documented in 2012 down by the canal, and, according to Mass Audubon’s Mark Faherty, they have nested in virtually every town on the Cape since then. I know there has been a nest at the Truro Transfer Station. And ravens attempted to nest in Provincetown a few years ago but were somehow discouraged. Elizabeth Brooke collected that nest, and it was massive.

Now they are back, building a nest on the northeast corner of Provincetown Town Hall. If you crane your neck and look up into a recess high on the building, a bulky pile of branches can be seen. If they continue and succeed, it will be the first common raven nest in town in recorded history.

Assuming that for most of you one big black bird is the same as another, allow me to persuade you to care.

We on the Outer Cape live in a paradise. Our wild neighbors present themselves to us daily: sea ducks, alcids, and loons that spend the winter in our harbors and ocean; warblers passing through in spring; the many shorebirds and terns that spend the summer and fall on our beaches.

The regenerative power of wildlife is unceasing, evidenced by the gray seals and white sharks in our waters (like it or not) and the coyotes, foxes, and fishers in our woodlands (and neighborhoods). A while back we had a black bear visit the Cape; last year it was a bobcat in Wellfleet; and a few months ago, a gray whale was sighted in the Atlantic. Ospreys and even bald eagles are becoming commonplace. Wildlife never stops looking for openings and opportunities.

Ravens were probably here long ago but were extirpated because they did not fit the business plan of the colonists. Now we do not shoot big black birds — at least, most of us don’t — and we are somewhat charmed by all creatures great and small, whereas our predecessors had a much more transactional relationship with them.

Ravens are extremely human-oriented. They were called “wolf birds” because they followed wolves around to share in their kills; now, out West, they respond to the sound of the hunters’ gunshots for the same reason. The common raven is by all accounts the most intelligent of the birds we live with. According to biologist Bernd Heinrich (Mind of the Raven), they have the highest encephalization ratio (brain to body size) of any bird, twice that of the crow and nine times that of the pigeon.

Heinrich has shown that ravens are not only scary smart but larcenous, playful, deceitful, duplicitous, and scheming. These are all human behaviors as well that can sometimes be observed both inside and outside town hall.

Was it the building that attracted the birds or the activity within and around it?