What must it have been like to live on this landscape a thousand years ago, before the Europeans came here? I sketch objects in museums and map them onto the timeline of human experience as a way of studying evidence of a different way of life. They make me look at my collections of keys and bicycles and kitchen tools differently.

When Provincetown’s middle school students, sleeping bags and snack bags in tow, venture out to the dune shacks for their October overnight stay, I go along as navigator. The two-mile walk has the young gamers groaning at the indignity of the plod, and there is nervous laughter about using an outhouse and “flushing” with popcorn and sawdust.

But the little hardships are forgotten in the face of open-sky freedom. They run for the horizon, fan out into nearby dune hollows, and create their own little encampments. They scrutinize their finds: a bleached crab carapace dropped by a gull, a deer vertebra, or a puffball fungus. The novelty of pumping water from the ground and the paradox of pouring away the jar of priming water is an act of faith that the Earth will deliver abundance to fill many buckets.

I ask each of them to imagine an 11-year-old girl living in this landscape 6,000 years ago, about twice as distant in time as the earliest civilizations in Egypt or Mesopotamia.

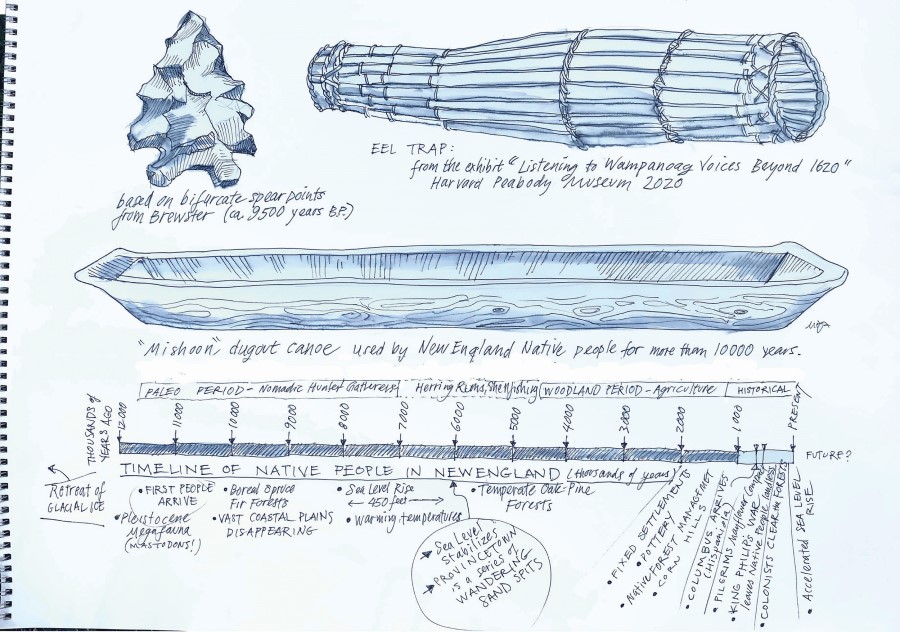

In so many ways we are the same humans as those we encounter when going back in time to the early evidence of the First People. Native traditions don’t account for a fixed date of arrival, but we know human migration followed the retreat of the glaciers some 18,000 years ago.

The landscape then would have been familiar in some ways: vast coastal plains extending to the little range of hills now known as Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard islands and covered with northern spruce and pine forests like what we now see in northern Maine.

The connected lands would have supported good hunting and habitat for deer, but also for the prehistoric megafauna — mastodons and mammoths, giant bears and walruses — that would soon disappear because of human hunting and the rapidly warming continent.

I imagine the dunes and marshes then as benign as any Eden, populated by wandering bands of people, drawn here by the herring runs and shellfish, the beach plums, cranberries, and black cherries, the acorn mast.

Places like the one we call High Head in Truro were perfect settings for camps from which to fish, forage, and hunt the surrounding marshes. But the land that is now Provincetown was still unformed 6,000 years ago — it would have been nothing but shifting tidal flats and twisting shoals, merging over a few millennia into dune ridges, bogs, and pockets of beech and oak.

In the last few thousand years people settled into a more fixed pattern of villages. These were many centuries old by the time the European fishermen and trappers brought smallpox and market consumerism to North America. For hundreds of generations, human life was woven into this land, and thousands of years of memory would have shown how human ecology thrived through times of massive coastal geologic change.

Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Indigenous Writing From New England, published in 2014, is one place to find echoes of the long unrecorded history of what it must have been like to navigate these lands and waters — which happened less often by roads than by dugout canoe. It includes the tale of Moshup, the Aquinnah hero-giant, who was annoyed at his wayward children and scraped a channel in the sand with his moccasin. The waters rushed in, stranding his offspring on an island — a story that could echo the human species memory of living in a glacial landscape of rising waters, new islands, and shifting sands.

In a moment of stillness, the students on the dunes close their eyes and imagine themselves wearing deerskin and woven cloth, eating dried herring, and encountering giant furry elephants in dark, mossy coniferous forests.

The fantasy is broken as they scuffle over bags of little orange fish crackers and perfect giant apples from modern orchards, a sweet comfort they prefer to tart sour wild cranberries, raked from a muddy bog.

Mark Adams is an artist, cartographer, and biologist.