It’s been more than a month since a juvenile humpback whale washed ashore, dead, on the inner beach near Long Point Light in Provincetown. News like this circulates and the whale becomes a reason for the 40-minute walk across the breakwater jetty in the West End.

You might see this walk as a kind of pilgrimage, taken out of curiosity about these giant mammals and a feeling that they have something to communicate to us. But the journey can also feel like ambulance chasing — there are people who ponder the bones as potential trophies, though that is strictly illegal under the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972.

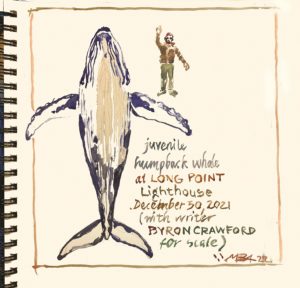

Still, the closing of a year full of collective trauma calls for moments of contemplation, so I set out with a friend and philosopher, Byron Crawford, to be in the presence of a whale.

Does every great or small creature we encounter present a message about the state of nature? We can’t help trying to divine clues. This young cetacean probably starved to death, perhaps after being so debilitated by repeated entanglement with fishing ropes and by infections that it didn’t have the energy to feed.

Understanding nature as a web in which we live will better equip us to create a more sustainable and resilient world. Yet humans can be interlopers, disrupters of the web’s delicate balance. To observe another animal can deliver us a spiritual charge but also cause disturbance from which the animals may not recover.

I’ve had indoor visitors from the Truro woods: sparrows, bats, snakes, and a praying mantis whose eggs hatched and swarmed my computer keyboard. Feeling the heartbeat of a sparrow as you release it is my definition of awesome. Cape Cod humanitarians ferry injured birds to Wild Care in Orleans, but even this sort of intervention is not always a success for the animal or the ecosystem it came from. Injured animals can seldom be released successfully. Relocating animals is almost never a good idea, because every habitat supports its own community and is essential fully occupied. There are few vacancies in nature.

Even though the humpback whale has been removed from the endangered species list, the Gulf of Maine population is still being assessed. It is probably fewer than 2,000 individuals. Entanglement expert Scott Landry at the Center for Coastal Studies says, “Whale conservation is hard, especially in the urban ocean of the Gulf of Maine.” The whale at Long Point reminds us of our culpability in whales’ deaths through our reliance on the shipping and fishing industries.

“We’ve never seen a whale die of old age,” says Landry, “so, we don’t know what that looks like.” A well-studied humpback named Salt has been returning since the 1970s, but scientists still don’t know much about these whales’ life spans.

As for the impulse to take home a piece of such a venerable animal, Landry says, in a word, “Respect. These are not decorations.” And disturbing their corpses interferes with scientists who want to study them, he adds.

The Long Point whale is dead but still full of life: seabirds, tiny shrimp, and microbes will take it apart with expert efficiency over the coming months. Byron waves his hand over a giant pectoral fin, disturbing a little swarm of creatures.

Byron and I agree that a ritual feels right. He reads a passage from John Milton’s “Lycidas,” written in 1637 and commemorating a friend lost at sea: “He must not float upon his wat’ry bier/ Unwept, and welter to the parching wind,/ Without the meed of some melodious tear.”