WELLFLEET — In the middle of the current racism pandemic, many of us who are not black or brown — who do not worry that our sons will be murdered while jogging — are wondering what we can do.

One white woman from Brewster, Peggy Jablonski, spent eight Wednesdays this summer walking all 15 towns of the Cape on a personal journey to reflect on racial injustice. Beginning at the Canal on July 8 and concluding in Provincetown on Aug. 26, she welcomed others to join her on the “Cape Cod Camino,” fashioned on the Camino de Santiago, the “way of St. James” pilgrimage in Spain.

I joined the Wellfleet portion in week seven, walking five miles from the bike path parking lot in South Wellfleet to Ocean View Drive, then along Cahoon Hollow Road, across Route 6, and up Main Street, ending at Preservation Hall. Though I was drawn to the idea of the walk, an opportunity to spend time with like-minded others and an exercise challenge, I worried that a stroll along beautiful Cape Cod byways smacked of white privilege. Black men were being shot, Covid deaths in communities of color continued to soar, and we were going for a walk?

But the intentions of the walkers moved me. We were to think about the places where we walked, to reflect on the systemic racism built into our communities of privilege, to educate ourselves, and to commit to change.

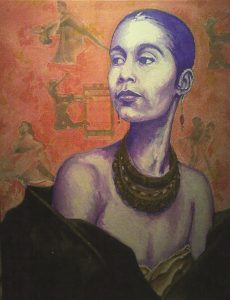

Each week had a different theme; week seven’s focus was black, indigenous, and people of color in the arts. We learned about Robin Joyce Miller’s fabric art and Pamela Chaterton-Purdy’s mixed-media icons of the civil rights movement, on display at the Zion Union Heritage Museum in Hyannis. We heard poetry by Joy Harjo, the first Native American Poet Laureate of the U.S. We were introduced to visual artists Shirin Neshat of Iran, and Aaqil Ka of Brooklyn, when our youngest walker displayed their work via her phone. We acknowledged the Wampanoag land over which we were passing.

We were also asked to pay attention to our bodies. Before LeCount Hollow Road turned left to become Ocean View Drive, my breathing became labored when I talked and walked at the speed of the others. The oldest in the group, I was humbled to realize I was the slowest.

When the walk ended, we were encouraged to participate in follow-up reflections on the pilgrimage. To my surprise, this was where the work deepened.

I grew up in the South with racism I couldn’t accept but which I certainly understood. What surprised and saddened me was the racism I discovered when I moved to Cape Cod. The Mason-Dixon Line didn’t divide attitudes in the past, just as it doesn’t today. The Cape’s history, like the South’s, is America’s history, rooted in slavery.

The deeper work of the Cape Cod Camino was finding these historical truths. Provincetown benefited from the salt cod industry that fed enslaved people on plantations in the Caribbean. The mansions of ship captains, today charming bed-and-breakfast inns, were built with shipping wealth directly tied to slavery. After slavery was outlawed in Massachusetts, a strong anti-abolitionist movement took root here. During an 1848 anti-slavery convention in Harwich, 2,000 people stormed the meeting and ran the abolitionists out of town.

Times changed, and, 12 years later, the Cape Cod Anti-Slavery Convention in Harwich Exchange Hall insisted on “immediate and unconditional abolition.” Historian James Coogan has noted that the Cape’s history of slavery and its changing attitude towards abolition remains an “ambivalent legacy” whose scars are still felt in our communities today.

My husband and I have a sign in our yard, “Black Lives Matter to Cape Codders,” distributed by Indivisible. Someone tried to remove it from its wire holder, but, unable to pull it loose, simply tossed it onto another part of our lawn. Did someone want it for a souvenir? Probably not.

Our challenge remains to have conversations with our friends and neighbors, and even our families, about the need for racial justice. Maybe taking a walk is a good place to begin.

Candace Perry writes plays, short stories, and essays.