In his basement studio in Wellfleet, John Best is sweeping fragments of glass out of the way, searching for his early-1900s optician’s pliers. He finds them: the business end of the rusted tool is wonky; the two sides of the clamp don’t quite line up. “But it does a great job at grabbing something and snapping it,” says Best.

Now, for a piece of glass. “Stretched out over this entire basement,” Best says, “there are about 1,000 sheets of art glass.” He collects unusual examples, sourcing single sheets from glassmakers like Ed Hoy’s International Art Glass & Supplies in Illinois, Rainbow Art Glass, Inc. in New Jersey, and Bullseye Glass Co. in Oregon. One sheet is lime green, with a rivulet of clear, shimmery color down the middle. “Bullseye called it ‘dribble glass,’ ” says Best.

He’s got a number of sheets of “drapery glass,” which folds over itself like moving water or luxury clothing. There’s an antique, one of many: a mouth-blown sheet from the 1930s in brown and red and teal. He brings out a sheet of hand-wrought “painterly” glass. Most modern glass has “dead spots,” he says — places where little or no movement occurs. Not this piece. It’s from Schlitz Furnaces and Studios of Milwaukee, a factory no longer in business.

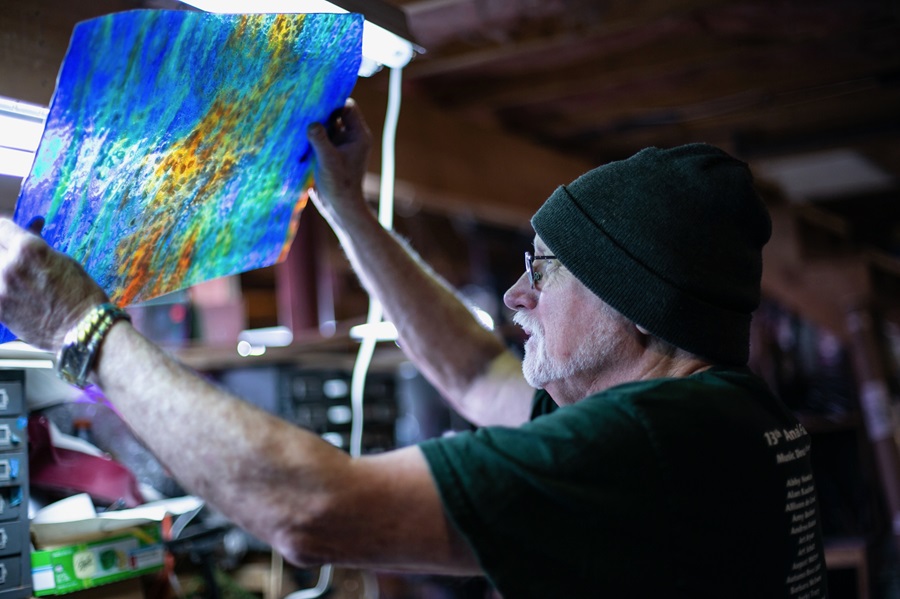

Best lifts another sheet. In seven colors, it seems to glow with its own light. It was made by a 1970s-era art glass manufacturer, Uroboros Glass in Portland, Ore., now closed. “They got into an argument with the governor,” says Best, referring to what happened when cadmium pollution was found near the plant. Making glass involves dangerous materials. “You need cadmium — oops, poison; cobalt — oops, poison; uranium — whoops.”

Best puts the sheets away, carrying them to one side as he walks. To hold them above one’s feet would be risky. “It’s a guillotine,” he says.

For the piece he’s working on today, Best chooses a long strip, its blue and green mottled and swirling like a pond blooming with algae. It’s a piece of “head and tail” glass, he says — the bit cut from either the top or bottom of a sheet of glass, with an uneven, rounded edge. He’ll use this piece for the top of the new jewelry box. From February to December of last year, he made 180 of them.

The boxes complement the work done by Best’s wife, Elizabeth, a jeweler and artist who also works in the basement studio of the house they built here in 1996. They call their joint operation Best Studios. They met while teaching at Glenfield Middle School in New Jersey, where Elizabeth was head of the art department, and John taught music. “We’ve been working together since 1970,” he says. It was Elizabeth who, back then, encouraged him to take a class on working with glass. Now, Best finds himself wondering, “How does the glass speak?”

Although she’ll offer her husband constructive criticism on the interest and variety of glass shapes in his pieces, Elizabeth doesn’t critique his color sense. Best says he has a preternatural understanding of color.

“Sometimes I’ll come up with the most perverse color combinations,” he says. He recalls a time he was working on a fluorescent green, electric blue, caramel, and bubblegum pink piece at a craft show. “I won’t allow you to make that,” one guy told him. But the next person to come along saw its beauty. “It’s not done yet, but I’ll take it,” he said.

To a visitor entering the studio, Best recommends closed-toe shoes and heavy-duty pants. With every step, there is a crunching sound: glass shards underfoot. And he uses solder to seal pieces together, melting the metal with a hot iron.

Everywhere there are large sheets of multicolored glass: it’s stacked on racks and balanced carefully against walls and tables, filed away like paper in cabinets and drawers. There are half-finished jewelry boxes and handmade windows, containers of scrap glass, and hefty machines like bandsaws in the corner for when hand tools won’t cut it.

Best places the slab of blue and green glass on a piece of scrap wood. Then, with a flick of his wrist, he throws an old, rusted horseshoe nail at the board. It sinks into the wood, tight against the glass. A few more nails knocked into place with the bottom of a converted putty knife and the glass is secured on all sides.

“Best tools, horseshoe nails,” he says. He bought them in bulk from a long-gone junk store in Provincetown. “They were selling whole boxes from the Spanish cavalry. About a buck a box.”

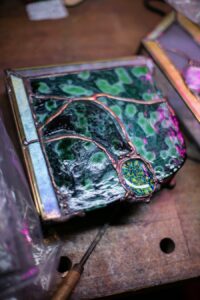

“The next thing I’m gonna do is frame it out,” says Best. He lines straight edges of the glass with a border of cheaper, solid-colored blue glass. “It’s a situation where you really don’t need to measure exactly, because I don’t like measuring exactly.” He’ll leave the natural, uneven edge of the main piece as it is.

He recognizes his avoidance of hard-and-fast rules as a matter of his own wiring. “The right side of the brain is talking to me,” he says. “Nothing else does.”

“Next step,” says Best. “We’ll go thingy hunting.” Elizabeth works with sterling silver and nuggets of dichroic glass — glass that changes color depending on the light. Best keeps cartons of small, rounded discards that she won’t use. They’ll become accents in his glass windows and on the lids of his jewelry boxes. Dust rises and glass clatters as he digs through a box of small, sparkling blobs. A square-shaped stormy-blue one will do. He places it gently on the main piece of glass in a spot that is otherwise comparatively plain.

On the workbench, he uses a black Sharpie to draw wandering lines across the surface of the blue and green glass. Those mark where he will cut. He traces the lines with a small, hand-held ball-end glass cutter. The sound is like creaking ice. He lifts the glass and knocks it two or three times with the ball end of the tool. Then, in his hands, the glass breaks easily along the line.

Best doesn’t wear gloves. “I’m in more trouble if I can’t feel the glass,” he says. Anyway, he’s got Band-Aids at hand. Next steps include wrapping the sharp edges of the glass in copper foil and then soldering everything back together. But he won’t get to soldering today.

He knocks and snaps, wraps and sets aside, repeats. “You can hear when the glass will break, because it goes from ringing to being dull,” he says. It sounds like music. “Why do you think people make wind chimes out of this stuff?” he says.

In the background, the Vienna Philharmonic is playing a symphony. The music plays at the same volume upstairs. Best works in the basement for five hours a day — it used to be eight — and then he’ll go upstairs and work in his recording studio.

Best was a classically trained violinist. When he moved to Wellfleet, he turned to fiddle. His band, which he started with Jean Sagara in 2007, is called Black Whydah. Upstairs he’s got something like 64 instruments: woodwinds, harp, a hammered dulcimer. “If it’s got strings, I’ve got at least two of ’em,” he says.

“I approach my glass like I approach my music,” says Best. “I never know what’s going to happen.”

Nearby, there are finished jewelry boxes in rosy purple and shimmering insect green. Brass channels around the edges of the boxes give them strength. Best lifts one to the light, tries the hinge, and says, “I want something that’s going to be around for a couple of generations.”