WELLFLEET — Down a sand road along the back of a kettle pond sits an austere one-story plywood-skinned rectangle on low stilts. Barely discernible from its surroundings, it was designed by Marcel Breuer in 1949 for his friends Gyorgy and Juliet Kepes. There are few windows on the side facing the road. The big openings, experiments in decks, porches, and glass, are reserved for more private views. A painting studio stands alongside, its north-facing wall of windows winking amidst the oaks and pines.

The Kepes house in Wellfleet was one of 12 stops on the Cape Cod leg of “Mass Modern,” a tour offered this month by Docomomo US, the American branch of an international organization devoted to the appreciation and preservation of modern architecture and design. At each stop, tucked away and efficiently arranged, was a small house designed by one of the 20th century’s most adventurous designers.

Peter McMahon, founding director of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust, was on board as a tour leader, along with Timothy Rohan, professor of art and architecture at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The two offered context to a group of about 20 travelers on the humble qualities of the buildings.

“We overlook the basic fact that some of the most influential modernist houses of the 20th century were vacation houses,” said Rohan — a fact that sometimes makes for “challenging habitability,” added McMahon.

“The first time it rained after Villa Savoye was finished,” McMahon noted, referring to Le Corbusier’s concrete house outside Paris, “rainwater poured in everywhere.”

Julie Stone was inside the Kepes house, preparing to close it up for the winter. “We are stewards of this house,” she said. The family has worked hard to resist making changes, she added, wanting to keep their parents’ vision intact.

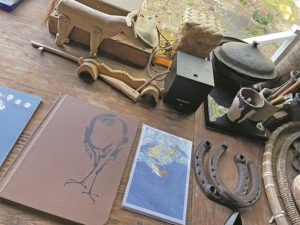

Stone’s father, Gyorgy Kepes, founded MIT’s advanced visual studies program; her mother, Juliet, was an accomplished children’s book writer and illustrator. In spite of the spareness of the building, its interior reveals abundant, even lush, vignettes: friends’ artwork, textiles, beach finds, books on a suspended shelf.

On a cantilevered screened porch that hovers just uphill from the water, a low table, made from a door, and a set of stools stay out of the sightlines to the pond. “My mother replaced the heavy folded paper woven seats on the wood frames with leather strips,” Stone recalled. “There were always materials around. Everyone was always making things.”

For Breuer, the house itself was a chance at out-of-the-spotlight tinkering. He later built a similar one for himself on Williams Pond, near the Truro town line. They were prototypes — he hoped the design might become a model for affordable modular homes.

Another stop: the Hatch house on Bound Brook Island is a floating series of 7-by-7-by-8-foot fir boxes, perched on pilings. When it was built in 1961, the house would have been completely exposed. Now, it emerges slowly, a weather-worn gray horizontal shape blending into the scrubby locusts and oaks and the bayside embankment. There are no windows facing the approach from Bound Brook Way.

Designed by self-taught designer-builder and Bound-Brook-Island-via-Boston resident Jack Hall, the house is as defined by voids as much as it is by the boxes that are its rooms, separated by open-air hallways.

It is October, so Gilly Hatch, a painter and printmaker who lives in England, and her husband, Thomas Gretton, are here for a stay as the house nears off-season uninhabitability. They are visitors here now, though the house was built for Gilly’s parents, Robert Hatch, then an editor of The Nation, and his wife, Ruth, a painter.

The house has been owned by the National Park Service since 2008. Through a lease, the Modern House Trust has restored it and become its steward. But the Hatch family has stayed involved, installing original furnishings and artwork after the restoration was completed in 2013.

Moving into the sun at the corner of the deck, Hatch recalls being shown as a child how to stand against the second post at night, look past the vertical edge of the house out over the bay toward Provincetown, and up — there’s the Pole Star, true north. A dashed diagonal line was painted across the sweep of the cedar decking. Over many years, Hatch remembers, the cedar, laid on edge, see-through, wore gently, but the painted line remained raised — a barefoot reminder to gaze upward from one’s own to the celestial bodies above.

These houses were laboratories of sorts, built to serve and challenge their inhabitants and their surroundings. At the same time, lives were led here, people grew up here, made things here, looked out at the world from here. It seems only right that these houses’ tinker-pedagogy still inspires.

Jenny Monick is a director of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust. The trust hosts artist and scholar residencies at the Hatch cottage (1961), the Kugel-Gips house (1970), the Weidlinger house (1953), and the Kohlberg house (1961), all in Wellfleet.