As winter draws near, we lose more leaves to the wind each day. The ones that remain give the landscape a patina of russet, sienna, ochre.

The ground is covered in fallen pine needles and brown oak leaves. A closer look reveals oak apples, or oak galls among them. These small, round growths form after a wasp has laid her eggs inside a developing oak shoot — the tree responds by growing plant tissue around the eggs. Oak apples protect the wasps during their season of growth. The pinprick hole in each gall marks the wasp’s exit. Once you know what they are, you see them, like tiny discarded homes scattered about the woods.

In addition to their interesting relationship with wasps, oak galls have been used in ink-making recipes as far back as the Roman Empire. Iron gall ink was used for transcribing many important manuscripts and documents throughout history, including the 4th-century Codex Sinaiticus, a handwritten copy of the Bible.

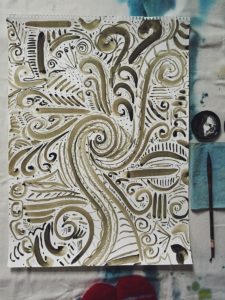

To create the ink, ground oak galls are soaked in water to achieve a dark brown, tannin-rich solution. Adding iron to the solution initiates a reaction that oxidizes the ink, so that as it is applied to paper, its color deepens.

The natural world offers many color possibilities for ink-making, even as plants begin their winter sleep. Consider acorns, bark, or berries to create a palette that is infused with the earth and soil of a place, that expresses the terroir of your landscape. Just make sure that, when walking the woods for ingredients, you forage responsibly and use caution when choosing plants; know what you’re working with.

Plant inks are generally made by cooking down one part plant material with two parts water. Additives like iron can change the ink’s intensity. Baking soda, salt, or vinegar will alter the color. Alum (aluminum potassium sulfate) acts as a mordant, which bonds the color to the paper for longer-lasting color. Alum can also brighten colors. Agar gum (made from seaweed) will thicken or change the consistency — good for printing on textiles.

A binder, like gum arabic (made from tree resin), acts as a glue to bind the color to the liquid, and to help make it more permanent. Add less binder if you’re using ink with a pen, as it will clog up the nib. Whole cloves, wintergreen oil, or thyme oil should be added to prevent inks from molding.

Keep in mind that color can fade or change over time once it’s applied to paper or fabric, also called fugitive color. Be ready to experiment, but take good notes and document your recipes and results, because some of your inks will be beautiful.

Basic Plant Ink Recipe

Yields about 4 oz.

Combine one cup water with ½ cup plant material, such as sumac berries, over medium-low heat. Bring just to a boil.

Lower heat to simmer and stir often until liquid is reduced by at least half and color deepens.

Allow to cool, then pour through a strainer to remove all plant material.

Pour into ink bottles.

Add gum arabic, if using.

Add one clove per jar of ink to inhibit mold.

Oak Gall Ink Recipe

Yields about 8 oz.

Grind 1 oz. oak galls to a fine powder.

Pour 8 oz. water over oak gall powder and soak overnight.

Strain through fine cheesecloth.

Add ½ oz. iron powder and stir well.

Add a few drops of gum arabic, if using.

Add one clove to inhibit mold.

Once applied to paper, the ink darkens as it oxidizes.

Note: this is acidic and may eat through paper over time.