On March 5, 1864, Massachusetts ceded jurisdiction of Provincetown’s Long Point to the United States for a military reservation. People in town didn’t like the idea much, although they did become fond of the officer in charge of the artillery there.

As early as 1821, an examination of the state’s coastline by the Office of the Chief of Engineers concluded that, owing to Provincetown’s geographical situation with respect to Massachusetts Bay, the harbor should “unquestionably be secured by sufficient batteries.” Then, in 1835, Major James Graham of the Corps of Topographical Engineers submitted a military and hydrographical chart of Provincetown “to aid in the projection of military defense works.” But it was not until 1862 that it was determined that the protection of the harbor from predatory expeditions of Confederate cruisers could no longer be postponed.

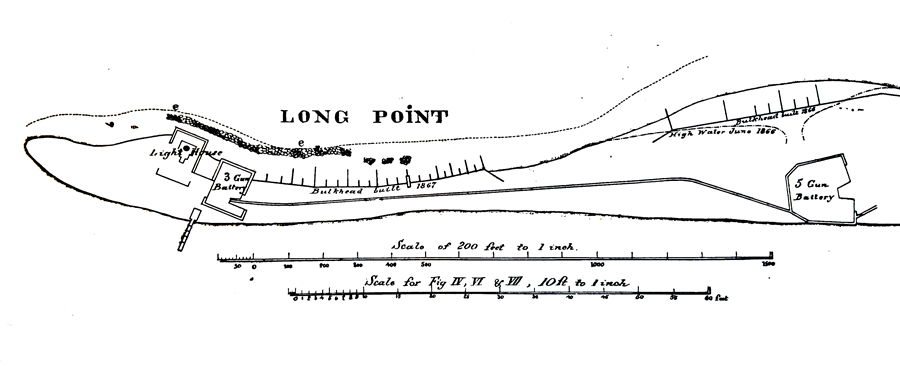

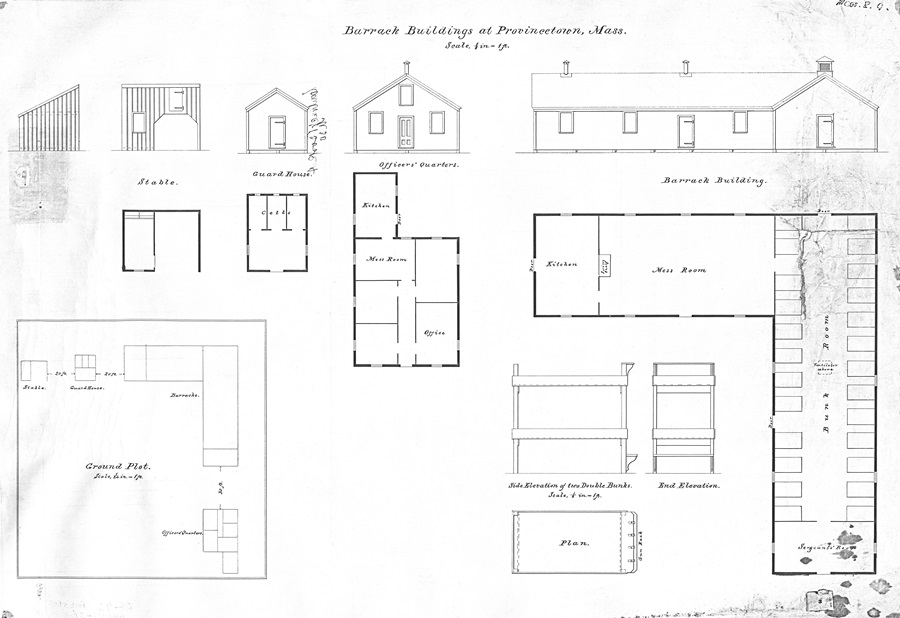

The reservation consisted of two earthworks batteries, one mounting five 32-pound smooth-bore guns (model 1829-41, 6.4-inch bore), the other mounting three guns of the same size and model, all on wooden carriages. A barracks, guardhouse, and stable were also constructed. The three commissioned officers assigned to the battery occupied one of the last buildings that remained from the Long Point fishing community that had been abandoned in the years before the Civil War began.

Provincetown residents scoffed at the notion that a fortification was necessary on Long Point even though the harbor, with its superb anchorage and shelter from storms, had been an important rendezvous point for enemy vessels during the Revolutionary War and War of 1812.

During the Civil War years, when Provincetown’s fishing and whaling fleets plied the Atlantic, mariners had become all too familiar with the reputation of the Confederate commerce raiders. At least six Provincetown schooners were captured and burned, and the formidable CSS Alabama, responsible for two of those captures, had cruised the waters off New England. The Confederate privateer Tacony was also harassing shipping along the coast. Undaunted, Provincetown vessels continued to go to sea, and unfazed residents mocked the batteries, calling them Forts Useless and Ridiculous.

For the 100 soldiers stationed on Long Point’s silent shore, life was no doubt tedious. A description of the batteries from the Department of the East notes that the nearest supply depot was Boston, that water was obtained in cisterns and fuel brought in from Provincetown, two miles north. A description of the “country” noted that it was “barren and sandy; no timber, or grass; no water, except rainwater; locality, healthy.”

The garrison of soldiers were members of Unattached Companies of Massachusetts Volunteer Militia, units of the infantry that were raised for the defense of the seacoast. Soldiers initially served 90 days, after which the battery was occupied by recruits serving 100 days until November 1864. They were subsequently replaced by one-year re-enlistments, who mustered out early at the conclusion of the war in May 1865.

Post returns from Long Point began in May 1864 and continued monthly until May 1865. Each return detailed the makeup of the garrison of soldiers as well as official communications received during the month. Most correspondence was routine, relating day-to-day business, but on May 15, 1865, the commanding officer noted receipt of two communications dated April 16 — the first announcing the death of President Abraham Lincoln and the second announcing that Andrew Johnson had taken the oath of office.

Taking charge of the artillery at Long Point was John Rosenthal. Born in 1833 in Alsace (then belonging to France), Rosenthal, a butcher by trade, arrived in New York City in 1853 and enlisted the following year at Baltimore in the United States Army. Assigned to the 5th Infantry, Rosenthal was sent to the frontier and saw a decade of service in the Indian Wars, first in Texas, where the regiment was engaged against the Comanches, later in Florida against the Seminoles, and in New Mexico against the Navajos. The regiment was also sent to Utah Territory in 1857 to quell the Mormon uprising.

In April 1864, Rosenthal was appointed Ordnance Sergeant and assigned to the Long Point batteries, where he remained in charge until 1876. Though the batteries were abandoned in 1872, at which time the artillery and other property were sold, Rosenthal remained as caretaker until being sent to the Dakota Territory.

After 31 years of faithful service, John Rosenthal retired in 1885 and returned to Provincetown. A year later, he became an American citizen. By 1892, it was reported that the Long Point batteries, under his watchful eye for so many years, were in complete ruins with little but small mounds of sand remaining.

During his time in charge of the batteries, Rosenthal had married Mary Freeman, whose father, Prince Freeman, was the first child born on Long Point after the fishing village had been established. The couple had two children, Mabel, born in 1866, and Irving, born in 1869, who later established himself as a photographer and owner of several gift shops in Provincetown.

For many years, Rosenthal served as Provincetown’s tax collector and managed Nickerson’s Whale and Menhaden Oil Works at Herring Cove, an enterprise established in 1886 by Capt. Joshua Stickney Nickerson, whose whaling steamer, the Angelia B. Nickerson, was named for his wife, the former Angelia Freeman, sister of Mary Freeman Rosenthal.

After falling ill in late 1914, John Rosenthal was admitted to the private Cambridge hospital of Dr. Henry Marcy in late January 1915; he died there on Feb. 7. The selectmen of Provincetown issued a proclamation recognizing Rosenthal as one of the town’s most esteemed citizens, “one whose unfailing charity and genial companionship won the love of all.” They expressed their appreciation, love, and respect “for one who was as faithful to our town in time of peace as he was faithful to our country in time of war.”

More than 300 Provincetown residents, exceeding the town’s quota, served during the Civil War. Eighteen were lost, killed by wounds or disease. On Thanksgiving Day 1867, in Gifford Cemetery, the town dedicated a magnificent memorial obelisk of Italian marble, inscribed with the names of the fallen and with emblems of the Army and Navy.