The oldest of Cape Cod’s old-timers could not remember when it had been colder or when more ice had piled up in the harbors. January 1875 had begun seasonably enough. But by Jan. 10, the first lows of an intense and long-lasting cold front were being felt along the New England coast. A reporter who called the weather “rather cool,” was met with a sardonic retort: “It was forty degrees below zero last night and each degree as long as your leg.”

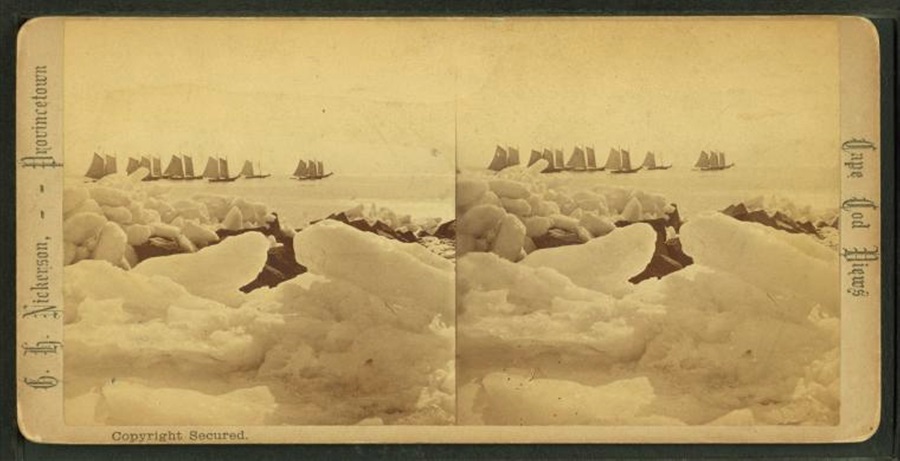

By early February, ice was forming on the flats at Brewster. Several days later, a slight breeze had grown to a violent wind, pushing drift ice into the bay and extending the ice field miles offshore from Provincetown to Sandwich. As February wore on, the Arctic cold and gathering ice persisted, closing harbors that had always been the sailors’ refuge, paralyzing commerce, trapping dozens of vessels, and putting seamen in peril.

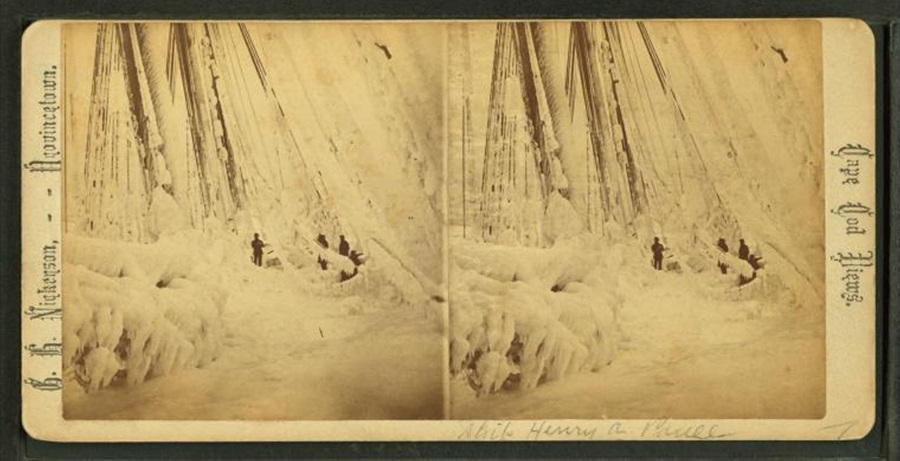

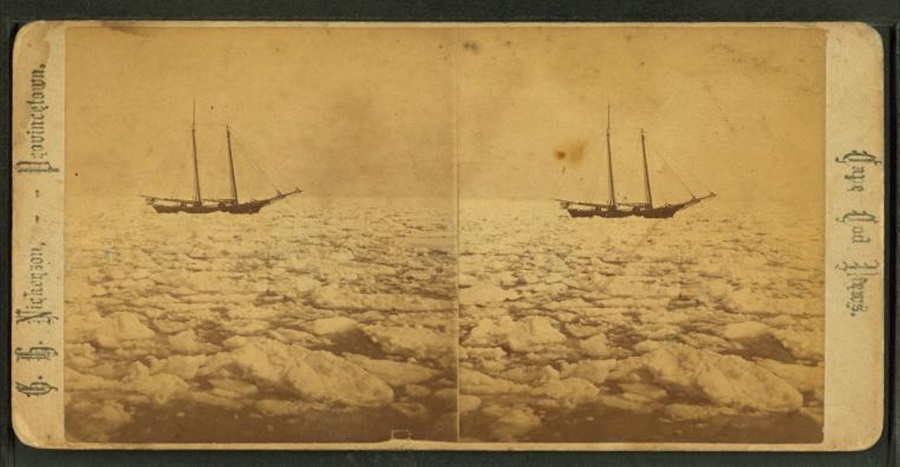

The situation was especially dire at Provincetown, where vessels from Boston, Gloucester, and Provincetown, trying to either round the Cape or make harbor, were caught in the ice. Some schooners were pushed ashore, their decks washed over by breakers and massive ice floes. Others sank, crushed by ice. Some vessels, surrounded by drift ice that seemed to serve as a protective cocoon, floated aimlessly in the bay wherever the ice took them. Still others, their masts flying distress flags, were locked in ice miles offshore. One report noted that the ice-crusted spars and rigging resembled ships of glass. What had been an expanse of rippling blue water had become a desolate and ragged icescape.

At first, with food and fuel running low, newspaper accounts warned of starvation and frostbite for those on board these ships. But soon readers were reassured that, as distressing as the situation was, communication had been established with land: dories and sleds were being pushed across the ice to deliver provisions to those who had opted to stay with their vessels. Then, too, many had decided to make an arduous and perilous hours-long walk across the ice to safety.

From her home port of Boston, the iron-hulled United States Revenue Cutter Gallatin was dispatched to render aid. Commissioned in 1874, even the 140-foot Gallatin was initially unable to reach the stranded mariners and was forced back to Boston. On return trips, she successfully delivered provisions and assisted crews in breaking ice and opening channels, releasing more than a dozen vessels here.

The Boston Daily Advertiser reported that the Gallatin crew had been “untiring and self-sacrificing” in providing aid and provisions to the “unfortunate sufferers.”

Among the vessels cast upon the shore near Provincetown’s Wood End were the three-masted schooner Henry A. Paull, en route from Boston to Baltimore in ballast with a crew of eight. They stayed with the ship for several days, abandoning it when waves and ice overwhelmed the decks. Nearby was the Provincetown-owned two-masted schooner Grenada, said to be in “worthless condition” by the ice, though her captain and crew had made it to safety.

The plight of the schooner John Rommel, Jr., hailing from New Haven, may have been the most unfortunate. Sailing from Mosquito Inlet (now Ponce Inlet, Fla.) to Boston with a cargo of live oak timber, she attempted to make harbor, foundered on the sand bar, and lurched onto the beach. The crew of five held fast to the icy rigging and had severe frostbite by the time they were rescued by the lifesavers from Race Point Station. The cold proved to be too much for one crew member who dropped dead on the beach, a “frozen corpse,” while walking to the shelter. The captain and three others were taken to the Pilgrim House in Provincetown and later transported by the Gallatin to the Chelsea Naval Hospital.

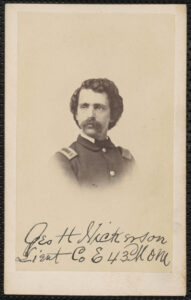

Documenting the Arctic winter, which finally loosened its grip after a month, was George Hathaway Nickerson. Born in Centerville in 1835, Nickerson had studied with the noted Boston photographer James Wallace Black before enlisting as a photographer in the Civil War, serving as a second lieutenant with the Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry in New Bern, N.C. Black published a series of photographs of the regiment camp taken by Nickerson.

By 1865, Nickerson had opened a photography studio in Orleans, and by 1872 he had established himself in Provincetown, where he was later joined in business by Provincetown-born photographer William May Smith.

Nickerson died in 1890. A former commander of the Josiah C. Freeman G.A.R. Post, he was buried in Provincetown’s old cemetery (where his headstone indicates he was born in 1837). His obituary recognized him as a man of “unswerving integrity,” noting, too, that his “pictures have always been sought by people who recognized his skill all over the County.”

Nickerson created a portfolio of stereoscopic views of Provincetown that included ice scenes from 1875. Stereographs consist of two nearly identical photographs taken with a special camera whose two lenses simulate human binocular vision. Paired and mounted on cards and viewed through a stereoscope, the two photographs seem to merge, producing a “view” — the optical illusion of a single three-dimensional image. Stereographs were exhibited at London’s Crystal Palace in 1851, after which they were mass-produced and commercially successful, becoming a worldwide craze during the last quarter of the 19th century.

That so many of Nickerson’s subjects have been lost to time makes his “views” all the more historically and socially important. Fortunately, some of his images of Provincetown can be seen on the New York Public Library Digital Collections website.

“The mind feels its way into the very depths of the picture,” wrote Oliver Wendell Holmes in “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph,” an essay he wrote for the June 1859 issue of the Atlantic Monthly. The 3-D effect of Nickerson’s vivid ice scenes invites viewers to immerse themselves and linger, discovering details in the harrowing events of that frigid February.

Editor’s note: Due to a fact-checking error, an earlier version of this article, published in print on Feb. 20, erroneously reported the date of publication of Oliver Wendell Holmes article as June 1959 rather than 1859.